Ep. 1 – “Inventing Traditional” // Ep. 2 – “Champagne Is Technology” // Ep. 3 – “Born In Clay” // Ep. 4 – “Native Vines” // Ep. 5 – “On A Boat” // Ep. 6 – “What’s Voile Got to Do With It?” // Ep. 7 – “The House Phylloxera Built” // Ep. 8 – “Bordeaux Is A Murder Mystery”

Header image: “The Pyramids of El Geezeh, from the Southwest,” Francis Firth, albumen print made 1857, from the digitized public domain collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The image was made using the collodion process: wet, sticky, and fizzing on a glass plate exposed in a portable dark room (“a smothering little tent,” Frith called it). The process had been invented only six years before.

Human had been growing wine for at least four thousand years when the pyramids in this image were being built. (The earliest signs of viticulture in France would not appear until the pyramids at Giza had been standing for another two thousand.)

“Autumn, Vintage Scene” — wool, silk, and gold tapestry designed c. 1535 and woven in the mid-1600s, possibly by Gobelins Manufractory (Paris, est. 1662). From the digital public domain collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Not so long ago, Prosecco was a cloudy pét-nat. Barolo was pink and fizzy. Pinot grigio was the color of rose gold. And Sancerre was red wine.

Regions considered ‘classics’ have often been making wine for a long, long time — but the wine they were making for most of that history might not look much like what we’ve been taught to expect.

When was ‘traditional’ invented? And who’s making wines today that remind us of what came before it?

Further reading: “The Myth of ‘Old World’ Wine”, Punch (Nov, 2020). Interested in what we talked about when we tasted? Buy a recording of the live session here. Details on what we drank below:

FRANÇOIS ECOT, ‘Six Cépages’

Who made it? François Ecot. In the late ’90s, he was one half of what would become the OG natural wine importer Jenny & François. Starting in the early ’00s he was pruning and apprenticing with first-wave natural winegrowers like Hervé Souhaut and Thierry Allemand. Today, he lives in his grandfather’s house in Mailly-le-Château, in the Yonne, and both farms and purchases fruit.

Out of what? Vines that François replanted on an old vineyard and orchard site overgrown with bushes and trees that had been abandoned for about 80 years, taking cuttings from a murderer’s row of natural winegrowers to recreate the kind of mixed, co-planted massale selection vineyard that might have existed here before phylloxera.

From where? The Yonne, a region around the market town of Auxerre named for its principal river. We are on limestone halfway between Burgundy’s Côte d’Or and Champagne’s Aube. There are a lot of historical winegrowing villages here—Saint Bris, Coulanges-la-Vineuse, Tonnerre, etc—many of which were a bigger deal before the dislocations and destruction of the 19th century. After almost going extinct in the 1950s, one of these villages—Chablis—rocketed to international stardom.

Hey, what’s césar? An ancient cousin of pinot noir crossed with a red variety that made its way here to pinot’s birthplace from Iberia — so, we’re guessing legionnaires. (Oral tradition has it being brought and planted by Roman soldiers.) Dark, tannic, and vulnerable to frost, it’s rarely planted today and even more rarely seen alone.

LESTIGNAC, ‘Michel Michel’

Who made it? Camile + Mathias Marquet, who inherited a family farm in 2008. They were the first people on the farm to make and bottle their own wines rather than make a living selling grapes to the merchants; in addition to biodynamically farming 7 hectares of vines they also manage 200 fruit trees, keep chickens and sheep, and have been introducing new plantings to return polyculture to the place they cultivate.

Out of what? In this case, purchased fruit to supplement their production (they started this in 2017). This is sauvignon blanc and gris from a biodynamic producer 6 minutes’ drive down the road.

Made how? Fermented on the skins for about three weeks, then pressed off into a different container (concrete tank, in this case) to age through the winter and spring. This is basically how most red wine is made—but in this case, the grapes’ skins are gold and pink, instead of blue and purple. The result? Orange wine—also sometimes called ‘skin contact’, ‘macerated white’, or amber. Potato, potahto.

From where? Bergerac, one of the market towns in the hill country that was first used as a source for, and then supplanted by, the merchants of Bordeaux.

FABIO GEA, ‘Grignósca’

Who made it? Fabio Gea, a former corporate geologist who returned to the semi-abandoned vines his mother’s father had once cultivated around the village of Barbaresco. His grandfather had farmed all kinds of things, not just grapes — at one point as many as 200 different varieties. Today, Gea has reconstituted a little over a hectare of scattered vines (that’s the size of a major league baseball field). From this, he makes 18 different bottlings. You can read more about him here. The paper labels are handmade. He encourages you to reuse the bottles. He has amphora made from sandstone, and is experimenting with porcelain jars he makes himself; he calls these his ‘toilets.’

Out of what? He doesn’t like to say—but given the name (in Piedmontese dialect) we can surmise mostly (?) grignolino, an old variety of the Piedmont alongside other old, less celebrated varieties (ruché, freisa, brachetto) that ripens late and has a weirdly high number of seeds inside its berries—as many as eight. The name literally means “seeds” or “pips” in dialect. Seeds have tannin just like skins, so the result is a pale, thin-skinned grape with a crazy amount of powdery, mouthcoating tannic structure—if you make it like red wine…

Made how? Destemmed, macerated for part of the day in bin, then moved to glass demijohn and homemade porcelain jars. Bottled before fermentation is finished with zero sulfur addition. Fabio says: “The sugar is so you can drink this in the morning and fight a shark.”

“Workers leaving the factory, Thaon-les-Vosges,” anonymous, postcard addressed to Alphonsine Colin (1907). From the digital public domain collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Champagne is a cold, northern winegrowing region. For a long time, it grew pale co-ferments the color of onion skins and partridge eyes.

Champagne is a technology, refined over a hundred years by English shippers and German merchant families. A product of the long 19th century, it was the ultimate modernist beverage: dependent on coal, carried by railroad, advertised in mass-media Art Deco posters, its terroir fertilized with plastic garbage bags and carved up by WWI trenches, its boundaries defined by labor riots.

As a method, its manufacture spread far beyond the region’s borders, from Cincinnati to Ukraine. As a winegrowing region, its growers have been grappling with its contradictions ever since.

Details on what we drank below:

ALTA ALELLA, ‘Mirgin’ 2018 Gran Reserva

Who made it? Josep Maria and Cristina Pujol-Busquets and their two daughters, Mireia and Georgina. Josep founded the winery in 1991 and it was organic from inception. It’s definitely a medium-sized operation—they farm 60 ha, so you’ve got a team of full-time employees, a tasting room, and a bunch of different special bottlings (out of those 60 hectares they make as many as 50 different wines). Out of what? Three local white grapes that are the backbone of most cava production: pansa blanca (the local name for xarello in Alella), parellada, and macabeo. From where? Alella, a tiny seaside village 25 minutes northeast of Barcelona. What kind of champagne? Technology. (Xampán tech arrived in Catalunya in 1872.)

LELARGE-PUGEOT, Coteaux Champenois Rosé

Who made it? Dominique Pugeot + Dominique Lelarge; their three kids have also joined the family business. They farm 8.7 hectares—without herbicides for the last two decades, certified organic since 2014 and Demeter-certified biodynamic since 2017. Out of what? Meunier, destemmed and left on the skins for 30 hours before being bled off into used barrels for aging, bottled without sulfur or filtration. From where? Vrigny, in the Petit Montagne—the ‘little hill’ to the northwest of the Montagne de Reims, with sandier soils and a very specific face to pinot meunier, the kid picked last for dodgeball of champagne grapes. (They are just down the road from Prévost.) What kind of champagne? Region! Pink still wine from just outside of Reims.

JOSEF TOTTER, “Salon Helga”

Who made it? Josef Totter, who grew up in the Steiermark and worked as a motorcycle engineer for years in Austria and then Italy, where he was gradually turned on to natural wine. He was born on a farm, and in 2012 he decided to come home and change his (and Helga’s) lives. Out of what? Souvignier gris, a pink-skinned hybrid of bronner + cabernet sauvignon obtained in Freiburg, Germany in 1983 that carries genes from vitis species including rupestris, licencumii, and amurensis. Frost-hardy and resistant to almost all fungal diseases. (See also: “What’s a hybrid?“) From where? Vulkanland, in the southeast of the Steiermark, in Austria’s rolling green south. On the Jägerburg, the hilltop village where Totter is from, it’s hot (95 degrees) in the summer and cold in the winter, and you get a ton of rainfall. The local vinifera varieties he was farming had him spraying dozens of times in a growing year. Inspired by a couple of neighbors, he ripped it all up to plant PiWi. “To make wine without being addicted to industrial products is really nice. 😊” – Josef Totter What kind of champagne? Technology. 2018 base wine fermented in 300L barrels, aged for a year on the lees and then bottled; fermenting juice from the 2019 harvest was added to start a natural secondary fermentation, and after two more years on the lees it was disgorged in fall of 2021, just before arriving in New York for the first time. Josef made it, he says, because ‘we love to drink Champagne, but it’s too expensive.’

“Mastoid (drinking cup),” attributed to the Leafless Group, depicting Dionysius astride a donkey (Athens, c. 500-480 BCE), from the digital public domain collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

But how did it all begin?

Vines were domesticated in Central Asia, six or seven thousand years before the grapes on this cup were painted.

Our earliest evidence of winemaking survives as traces on pottery shards in archeological sites scattered through the Caucasus, in caves where clay fermenters were buried below stone grape presses, and in graves where men and women were buried with their drinking horns and clay pots.

In the preset-day Republic of Georgia, long used as a wine factory by the Russian empire, ancestral knowledge was kept alive out in the countryside by home winemakers. Real wine was what you got ladled out of your neighbor’s qvevri; fake wine came in a bottle from one of the factories.

The invasion in 2008 changed everything. And today, as these ancient wines are being revived and celebrated, they are increasingly being made by a new generation of women and outsiders who tradition would have never let in.

Buy a recording of the live interactive session here. Details on what we drank below:

NATIA CHEKURISHVILI, ‘Short Circuit’

ნათია ჩეკურიშვილი

Who made it? Natia Chekurishvili, who for years worked at Tiblisi natural wine bar Vino Underground before moving west. Out of what? Tsitska and tsolikouri, which along with krakhuna are the three main white grapes of the region. From where? Over 70% of the country’s grapes come from Khaketi, in the country’s east. Past the mountains, Imereti is the most important of the regions in the west. Lower in elevation, flatter, milder and more humid, its wines—often incorporating a lower proportion of skins, fresher and lighter than Khaketi ambers and dark reds—feel very much of a piece, and they may be a surprise even if you’ve tasted a lot of qvevri wine.

JANE OKRUASHVILI (SISTER’S WINES), ‘Kartli Field Blend’

ჯონი ოქრუაშვილი

Who made it? Jane Okruashvili, a political scientist who went into business with her brother, John (he used to be in telecommunications), to reconnect with their cultural heritage. They both make wine out of a small marani in the mountain fortress of Sighnagi. Out of what? A field blend of tavkvevri, shavkapito, and chinuri. (Chinuri is white, tavkvevri and the very rare shavkapito are black, although you can find light red / dark rosés now from them.) From where? Kartli, the central region outside of the capital of Tblisi.

KETO NINIDZE, ‘Obeluri Ojaleshi’

ქეთო ნინიძე / საოჯახო მარანი „ოდა“

Who made it? Keto Nindize, a university-trained linguist, blogger and social activist who moved to the far west in 2015 with her husband; both make wine, albeit separately. “Oda” is the local name for the two-story houses with a raised patio and cellar on the ground floor that are typical to the region. Out of what? Obeluri ojaleshi, whose name literally means “sun-lover”; it was traditionally trained up persimmon trees. Dark-skinned and capable of adding color to blends, it was instrumentalized under the Soviets for bulk factory wine. From where? Samegrelo, as far west as I ever got when I was in Georgia, with some dramatic terrain including lots of big pieces of chalk limestone in the ground.

“View of Cotopaxi,” Frederic Edwin Church, oil on canvas (1857). From the public domain collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The curator’s text adds, “Inspired by German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s concept of ecological interconnectedness, Church traveled to South America to meticulously study the tropical landscape … The painting likewise reflected an imperial vision, as U.S. government officials eyed Latin America as a site for territorial expansion and conquest.”

The history of winegrowing in the ‘New World’ doesn’t start in Napa, or with European vines. It has its roots in Mapuche fruit fermentations and North Carolina forests. It encompasses dozens of vine species that are native to the Americas, and goes back half a millennium.

From hybrid wines to own-rooted criollas, and from southern Chile to the Appalachian Mountains, we explored what it means to be a grape variety called ‘native to a region’, and tasted bottles that retell the story of American wine.

Buy a recording of the live interactive session here. Details on what we drank below:

AMERICAN WINE PROJECT, ‘We Are All Made of Dreams’

Who made it? Erin Rasmussen. Originally from Madison, she worked internationally for a decade in places like Napa and New Zealand before moving back home to start her own project; her first independent vintage was 2018. Out of what? Somerset Seedless, a pink-skinned table grape obtained by Osceola, Wisconsin grape breeder Elmer Swenson, whose work would form the backbone of the University of Minnesota’s cold-hardy program. Somerset Seedless is a hybrid that carries genetics from labrusca, riparia, and vinifera as well as small amounts of several other American vitis species. From where? Erin sources hybrids from as far afield as Minnesota and northern Iowa; her Mineral Point winery is in the heart of the Driftless Area, a rugged landscape of limestone carved by the Mississippi River, and the only part of the Upper Midwest not scraped flat by retreating glaciers. [more info]

ROBERTO HENRÍQUEZ, ‘Torrontél Super Estrella’

Who made it? Roberto Henríquez, who grew up in Concepción with Mapuche heritage and worked in wine internationally for years before moving back home outside of Nacimiento to make his own wines. Out of what? Torrontél, one of the many children of the co-planted pais and moscatel vines across the landscape of southern Chile, here fermented on the skins. From where? Bío Bío, the birthplace of viticulture in the west coast of the Americas, whose verdant greenery and red granite hills hide some of the oldest vines in the world.

NORTH AMERICAN PRESS, ‘The Rebel’

Who made it? Matt Niess, who departed a career making fairly fancy California wine out of the conviction that the state’s future in the face of drought and wildfire lay with exploring hybrids and fruit co-ferments. Out of what? Baco noir, one of the French-American hybrids (folle blanche x riparia) devised in the late 19th century in the face of phylloxera, once one of the most-planted varieties in the Loire Valley and still found in Armagnac. This particular vineyard was semi-abandoned, across a fenceline from some of the most expensive pinot noir in the county. From where? The Sonoma Coast. [more info]

“The Plantation,” ca. 1825, artist unknown. Oil on wood, possibly based on a needlework design. From the digital public domain collection of the Met’s American wing.

What happens when a wine becomes a luxury good traded overseas, instead of a food grown at home?

For Madeira, beloved of the Founding Fathers, it meant intentional sweetness, fortification with brandy, oxidation like a cut apple left out on a kitchen counter, cooking in the holds of slave-trading ships setting sail from Cape Coast Castle.

(After its journey, it would be served to those devotees at establishments like the Charleston Jockey Club, opened, tasted, and poured by the enslaved Black men who were the first sommeliers in the United States.)

Madeira is a unique wine from a unique place: a volcanic island off the coast of Africa that was deforested, then used for sugarcane production until the soil gave out, then terraformed into vineyard land growing varieties that today exist nowhere else in the world.

But, as a wine, it’s also just the most famous survivor of what was done to almost any wine that ended up on boats.

At the speed of oar or sale, if wine was traded, it was altered to survive the journey: pine resin, honey, herbs, salt water, lead.

Until the middle of the 19th century, Bordeaux was fortified with brandy and Spanish grape juice to endure the Channel crossing. Wines like sack, jerez, canary, and marsala were king. It was impossible to taste the sorts of fragile homemade wines we celebrate now outside of the back yard of the farmer who grew them.

“The Wine Connoisseurs,” Jacob Duck of Utrecht (c. 1640-1642), oil on panel, from the digital public domain collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Palomino is a grape that was put to work. Most famous for the vintage-blended, fortified, often sweetened sherries of Jerez that fueled the British empire, it also found itself in a lot of other places it’d been brought to by ships or autocrats.

(A few of those places: the Canary Islands, where it accompanied the Conquista under the name listan blanco; Galicia, in the wake of phylloxera, later to be encouraged by Franco; Cyprus, where it was used to bolster production of ‘Cyprus sherry’—by the 1960s, the British were drinking over 13 million liters per year of the stuff.)

Like a lot of workhorse varieties, what palomino can do has often been obscured by what it’s been made to do.

We peeled back the veil (literally and figuratively) to see what else these wines had to say.

Buy a recording of the live interactive session here. Details on what we drank below:

COTA 45, ‘Paganilla’

Who made it? Ramiro Ibánez, who began what he calls his ‘albarizatorio’ (albariza laboratory) in 2012. ‘Cota 45’ refers to the meters above sea level (45) where he thinks the albariza soils are the most interesting. Out of what? Listán aka palomino, which during the long 19th century and the sherry boom became the dominant variety planted in sherry country, partly for its ability to take biological aging, crowding out the 119 different local varieties documented at the beginning of the 1800s. From where? A pago (vineyard with a name) called Paganilla, from two plots on different types of albariza: cerrada (“very tough [chalk], almost cement-like”) and barrajuela (“deck of cards”, “horizontal laters of white chalk full of marine fossils, notoriously difficult to grow in”) Made how? Fermented and aged in old sherry botas, where they develop flor and age biologically under it for 3-4 months or so. Bottled without fortification or filtration in the spring.

LOS LOROS, ‘La Bota de Mateo’

Who made it? Juan Francisco Fariña Pérez, aka JuanFra, who started making wine here in the early aughts. ‘Los Loros’ refers to the laurel shrubs that grow in the valley. Out of what? 100+ year-old ungrafted bush vines of high-elevation listan blanco (aka palomino), in a part of the island that was economically important 200 years ago and has since been virtually abandoned. From where? A single parcel at almost 4600 ft elevation on volcanic clays, in Las Dehesas, in the east of Tenerife. Made how? Destemmed before pressing, fermented and aged in the same two old 500L Manzanilla barrels with no movement. Bottled without filtration.

CASA VIEJA, ‘Palomino’

Who made it? Humberto Toscano, who came home to the ranch he grew up on in 2003 to recuperate the 3 hectares of ancient vines on the property and seek a quieter life. Out of what? 120+ year-old ungrafted bush vines that never saw chemicals. From where? San Antonio de Miñas, in the Valle de Guadalupe in Baja California. Made how? Destemmed by hand on a wood lattice called a zaranda, fermented on the skins in a clay tinaja, pressed off into steel tank and bottled in the spring without sulfur addition or filtration.

“The Eruption of Vesuvius,” Pierre-Jacques Volaire (1771), oil on canvas, from the digital public domain collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. “Vesuvius erupted six times between 1707 and 1794, and thus became a touchstone of popular culture at the time.”

The landscape of modern wine, the regions and grape varieties we take for granted, was in a lot of ways invented by the mass extinction event of phylloxera at the end of the 19th century.

Phylloxera is a pale yellow, sap-sucking aphid. Endemic to the eastern United States, whose local vine species have evolved accomodations to its predations, its arrival in Europe in the late 1850s began a slow-motion ecological catastrophe: first the Languedoc, then France, then Europe, then the world.

It’s why almost every wine you’ve ever tasted has been amde from vines grafted onto rootstocks not their own. It’s why there are fewer than 300 hectares of scattered plots under vine in Isère, between the Savoie and the Northern Rhône, instead of 33,000. It’s why Rioja became a commercial wine region, bankrolled by Bordeaux money looking for alternative looking for an alternative to their dying vines.

And phylloxera was only the latest and worst of a series of crises caused by faster transportation, international trade, and ecosystem collapse—which makes its lessons much more than just academic for today’s winegrowers.

What was it like, the world we lost to the louse?

Buy a recording of the live interactive session here. Details on what we drank below:

MINGACO, ‘Pais’

Who made it? Daniela de Pablo and Pablo Pedreras, who practice regenerative agriculture and polyculture in the village of Checura. Their three hectares of vines and fruit trees were lost to wildfire this February. Out of what? A tiny plot of 150-200 year-old pais, the vine variety that arrived, along with moscatel, on board Spanish ships via the Canaries 500 years ago, and which died to fire last month (ed. — Feburary 2023). From where? Itata, named for the river just northeast of the port of Concepción, the heart of the Chilean natural wine movement, the birthplace of viticulture in the west coast of the Americas, and a landscape that has been reshaped, against the wishes of its indigenous stewards, by commercial forestry and eucalyptus cash crops. And after the fire? Here is a link to a gofundme set up by their French importer, À boire debut, to support them (scroll down for English), and to another for Leonardo Erazo, a producer dear to me who was also deeply affected.

JÉRÉMY BRICKA, ‘Verdesse’

Who made it? Jérémy Bricka, who worked for Guigal and founded the French whisky distillery Des Hauts Glaces in 2011 before moving to Isère and buying 5 hectares to plant and make his own wine. Out of what? Verdesse, an ancient variety that was nearly lost after phylloxera, and has enjoyed a tiny renaissance in the last decade; Jérémy has been slowly planting new verdesse since 2015, and the vines in this bottle are 3-7 years old. From where? Isère, a river that runs from the Savoie into the Rhône, and the conective tissue between the two regions — over 33,000 hectares under vine before phylloxera, less than 300 today.

PETIT GIMIOS, ‘Rouge Causse’

Who made it? Anne-Marie Lavaysse, who bought this farm in the hamlet of Gimios in 1993, and her son, Pierre. Her background was farming polyculture—she’d previously kept geese, ducks, goats, and cows. She left the co-op in the early aughts and, through making her own wine, got to like it. Out of what? A single, mixed parcel of 19+ red, pink, and white varieties—every color of terret, carignan, and grenache, muscat, aramon, cinsault, and more—planted on their own roots, before phylloxera, circa 1856. They acquired it, almost abandoned, in 2014. From where? A hamlet outside of Saint Jean de Minervois, in the western part of the Languedoc, in Mediterranean France.

“French Dining Room of the Louis XIV Period, 1660-1700,” Narcissa Niblack Thorne, miniature room scaled 1 inch to 1 foot (c. 1937) from the digital public domain collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Bordeaux is, without question, luxury wine’s greatest success story. It is the largest fine wine region on the planet, at more than 200,000 hectares under vine. For the last two hundred years, it’s had a stranglehold on the concept of ‘fine wine’ itself.

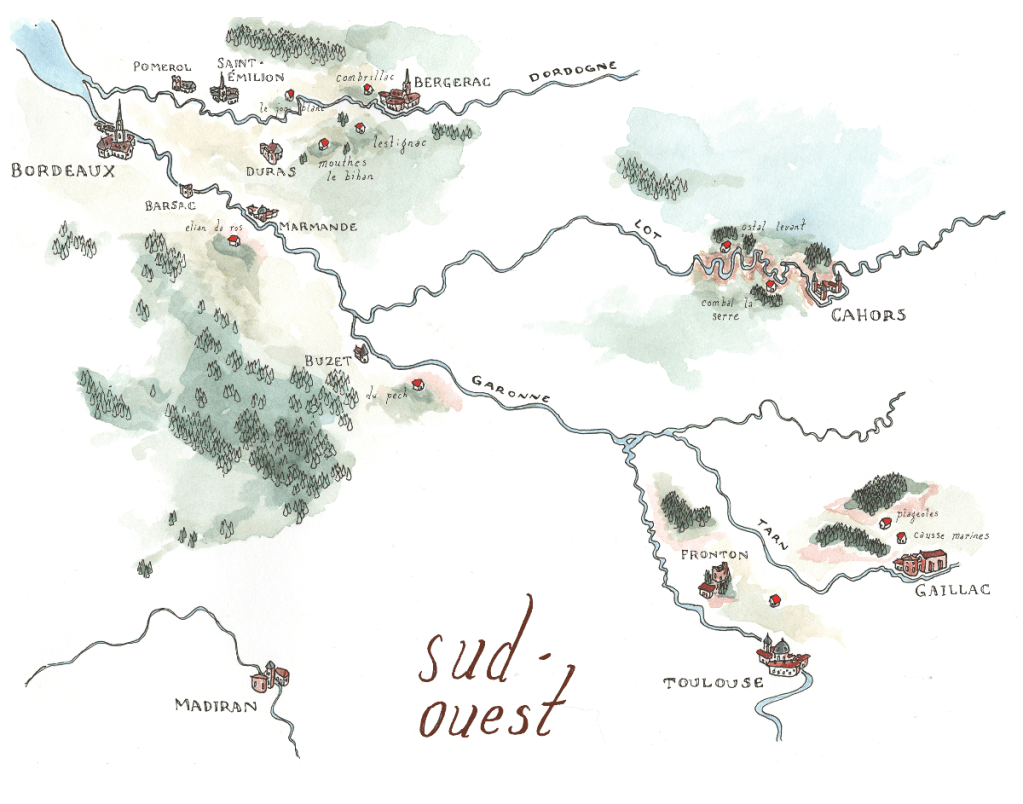

Its rise, first as a mercantile juggernaut, then as a winegrowing region in its own right, was built on the bones of places it got rich off of and then destroyed, from Buzet to Gaillac.

But up in the hill country, the survivors of the Sud-Ouest may have their own version of the story: medieval market towns perched on navigable rivers that empty into the Atlantic, with local specialties, native vines, and nearly forgotten winemaking traditions that date back as far as the Romans…

Buy a recording of the live interactive session here. Details on what we drank below:

PLAGEOLES, ‘Mauzac Nature’

Who made it? Florent + Romain Plageoles, who continue the work of their father (Bernard) and grandfather (Robert) in farming and preserving the grape varieties of their region. They work 20 hectares of vines in two different sites. Out of what? Mauzac rose, a pink-skinned variant of mauzac, a high-acid, apple-y variety historically used for sparkling wines in Gaillac and Limoux. Made how? Methode ‘gaillaçoise,’ the local name for a precise, controlled variant of pét-nat: the juice ferments until there are 30g/L of sugars left, at which point they bottle; it finishes fermentation (and develops soft bubbles) slowly over the next few months. From where? Gaillac, one of the three villages in Gaul whose wines were celebrated in the Roman Empire (Taim l’Hermitage and Côte-Rôtie in the Rhône were the other two). Gaillac is a treasurehouse of old local varieties that in many cases exist nowhere else: red grapes like prunelart, duras, braucol (also called fer servadou), and mauzac noir (no relation), as well as white varieties like ondenc, mauzac vert + rose, and loin de loeil. Many were saved here by Florent and Romain’s grandfather, Robert, at a time when the commerce of the region was moving towards gamay nouveau in imitation of Beaujolais, syrah-based blends, chemical farming, and bulk wine. Gaillac, like the Jura, also has an unlikely diversity of wine styles for a small place — not just reds and whites and sparkling but whites aged under flor, intentional oxidation, sweet wines dried on straw mats (vin de paille), and more—almost lost, these days.

MOUTHES LE BIHAN, ‘Vieillefont Blanc’ 2017

Who made it? Jean-Mary and Catherine le Bihan, farmers who organically grow cereals, sunflowers, and raise horses—along with 27 hectares of vines. They’re certified organic and are in the process of biodynamic conversion. Their first vintage was in 2000. Out of what? Sémillon and sauvignon blanc planted in 1925 and 1929, along with a bit of younger muscadelle — the typical proportions and grape varieties for dry white Bordeaux. The grapes are pressed slowly over 6 or 7 hours and fermented in large used barrel. They always keep it in bottle for a few years before release. From where? Duras, which is often lumped in with Bergerac — a region in the hills just inland of Bordeaux with the same grape varieties, as well as chenin — planted after the second world war for its ability to yield and be a workhorse.

OSTAL LEVANT, ‘Un Coeur Simple’

Who made it? Charlotte + Louis Pérot, who left behind literary careers in Paris to rehabilitate an old farm 30 miles west of Cahors: fruit trees, chickens and goats, 20 hectares but just 3 under vine. They were mentored by Cahors natural wine icon Simon Busser in Prayssac, where limestone terraces climb above the village and the river Lot. Out of what? Their oldest parcel of côt aka malbec, now the variety most associated with Cahors, deeply colored and made internationally famous by the juggernaut that is Mendoza malbec. It was planted in 1957, the year after the devastating frost of ’56, which marks the landscape everywhere here. There are no older vines in their village — they were all lost. Bordeaux was replanted, skewing red. Cahors became synonymous with côt. From where? The limestone and red clay terraces overlooking the hairpin turns of the river Lot, in the villages around Cahors. Like Gaillac, Cahors has a Roman past and was an important medeival trading town, whose boiled red wine paste, the ‘black wine of Cahors’ was shipped via England as far afield as Russia. Cahor’s back was broken by phylloxera, which hit the region in 1883-85.