An afternoon tasting series exploring how wine gets the way that it is and the ways that we talk about it, hosted in the backyard Pool installation of Hi-Note, a radio listening bar in the East Village. The next class, ‘Oak’, is on Sunday, September 8.

On Sunday, June 23 we looked at color vs style. How much of what a wine looks like gives you a good sense of what you can use it for? How many wine colors are there beyond white and red? What are some of the approaches that winegrowers are taking, right now, that change how your wines look in the glass? (And why do we care?)

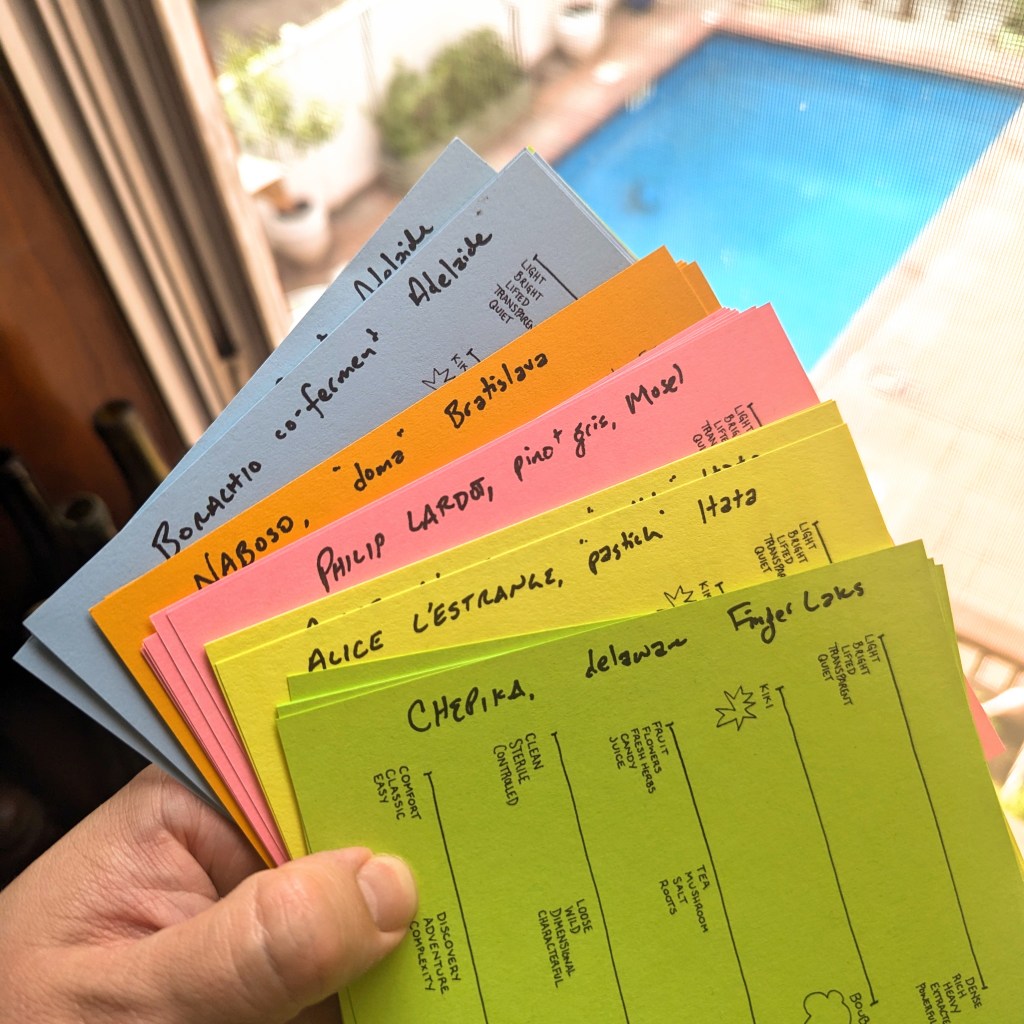

Here are more details on what we drank, who made it, and where you can get more:

Greeting, and how to taste on a spectrum:

CHËPÌKA, delaware FINGER LAKES

short version: white-ish wine from pink grapes! fizzy. points to the forgotten history of U.S. wine and American grapes.

Chëpìka (‘roots’ in Lenape) is a collaboration between Finger Lakes winemaker Nathan Kendall and galaxy brain sommelier (also my former boss!) Pascaline Lepeltier. The project revives the dropped thread of 19th-century American winemaking, an era when the heart of the U.S. wine industry was in northern New York and the Ohio River valley, and the wines were often champagne-method sparklings from native and hybrid varieties. (By 1860, catawba, a wild hybrid found growing in the woods outside of Asheville, was the most-planted wine grape in the country.)

Delaware, a pink-skinned variety known as ‘the jewel of American wine grapes’ before Prohibition, is today nearly extinct, planted on just a few dozen acres in New York. Here, it’s coming from Buzzard’s Crest, one of the very few organically certified vineyards in the Finger Lakes, New York’s most important wine region. (One of the ways they can farm organically? Delaware’s genetics are indigenous, and adapted to its local climate and pathogens.)

It’s been pressed off, fermented, and bottled with a little frozen juice from the harvest to start a natural second fermentation. After a year of aging on the lees (slurry of spent yeast from that second ferment) it’s disgorged, popping out the plug of yeast sediment and leaving a clear wine. Delaware has a creamy, textural character that plays really well with lees aging (I think about Nilla wafers), and a tropical lift to that creaminess that reminds me of the white center of a kiwi.

where to find? You can order directly from Nathan at the winery.

‘Orange wine’ plus:

ALICE l’ESTRANGE, moscatel, ‘Pastiche’ ITATA

short version: a perfumed, ancient aromatic white grape with skin contact (push aromatics to 11!), aged under a veil of yeast (turn aromatics savory/smoky!), from a place that turns New World v Old World on its head

The lush, red granite hills around the Itata River in southern Chile, inland of the port city of Concepción, are cradle to some of the oldest vines in the world: two, three hundred years old, in some cases. The region, historically marginalized and remote from the capital, was more likely to see those vines torn up for eucalyptus and pine plantations or their fruit disappear into bulk wine bottled up north.

But Itata is also a repository of ancestral fermentation practices and styles of wine that can be revelatory if all you expect from Chile are cheap knockoff Bordeaux blends. Here, 100-150 year-old own-rooted moscatel (muscat of Alexandria, more on that here), along with small bits of other varieties, is hand-destemmed with a bamboo lattice called a zaranda into sealed bins and tinajas (clay jars). The soupy mixture of broken berries and juice ferments without crushing, and is then pressed into steel tank, where it develops a veil of living yeast that protects it from oxygen and changes the wine underneath.

So there’s skin contact here, but it’s very gentle — and a lot of the wildest aromatics come from the flor aging making moscatel’s perfume salty-yeasty-smoky.

Alice l’Estrange isn’t a native of Itata — she’s Australian, and moved out here to be part of the region’s burgeoning natural wine movement, a place, she says, “where social and environmental concerns take front and center.” (Indigenous water rights and wildfires exacerbated by commercial forestry are live issues here, and feed directly into what’s happening with the vines in the ground and the people who farm them.)

She works with three local growers who have transitioned to no-till regenerative practices, and also has a project called Las Fermentadas that works to empower local women in wine.

PHILIP LARDOT, pinot gris MOSEL

short version: when orange wine is ruby-red, in riesling’s home. where does this go on your wine list?

What happens when you make ‘orange wine’ out of a pink grape? Pinot is an ancient variety, and one of the ways we know that it’s been around the block is the spectrum of mutations that have accrued over the centuries of it being propagated. One of the easiest to see? The color of the grapes. Pinots blanc, gris, and noir are all genetically one cultivar — just different color mutations of the same variety. (You see this with other old varieties, like muscat, carignan, or grenache.)

This pinot gris is coming from a tiny parcel of young vines in a vineyard named Falkenberg (‘falcon’s rock’) on the plunging slate terrace slopes overlooking the Mosel river around the village of Piesport — normally ground zero for classic German riesling.

The grapes were destemmed, crushed, and fermented on the skins for nine days with very gentle infusion (pressing down the cap of skins into the fermenting juice with your hands instead of punching it down with a tool or pumping the juice over it). Pinot gris is often a bit of a chameleon, most often associated with highly manipulated, sterile white wines out of northern Italy (cf. Santa Margarita pinot grigio), but also capable of a whole spectrum of color and style, from slightly coppery to bronze to electric pink to deep ruby.

Co-ferments:

BORACHIO, pinot noir, pinot gris, chardonnay BASKET RANGE

short version: kitchen-sink blend of foot-stomped grapes, whole cluster infusion, and direct-press juice. light red, dark rosé, what’s the difference? from part of the new wave of wild, fresh Australian natural wine emanating from the Basket Range behind Adelaide.

The ‘short version’ kind of says it all, but here’s the nitty-gritty! Core of the wine is foot-stomped pinot noir, pressed off after a few days (“dark rosé”). To this is blended in a few other ferments: pinot gris juice with whole clusters of pinot noir floated in it, a little bit of carbonic pinot noir from tank, and direct-press, barrel-fermented chardonnay.

It’s made by Alicia Basa and Mark Werner on Kaurna land in the McLaren Vale, from fruit farmed by friends and collaborators there and in the Basket Range, bottled without anything added or taken away.

NABOSO, blaufränkisch, riesling, grüner, ‘Spolu’ BRATISLAVA

short version: red and white grapes together in the same pot, across the Danube from Vienna

Co-ferment can mean a lot of different things in practice, but the short version is captured by the name of this wine: spolu, or “together” in Slovakian. Sometimes, as here, that means red and white grapes; sometimes it means grapes and other fruit.

Sometimes it means harvesting a single vineyard full of a lot of different vines at the same time and fermenting everything together (this is also often called a “field blend”). Sometimes it means progressively adding fruit picked at different times to a continuous fermentation, like feeding a stockpot. Sometimes, it’s used for wines blended from different lots of red and white grapes with and without skin contact that weren’t actually fermented together, because it’s an easy shorthand for something that people enjoy drinking but don’t necessarily need explained in detail. (I might cheat and call the Borachio a co-ferment tableside, for instance.) And for most of the history of humans making wine, co-fermentation along these lines would have been the norm.

Here, it truly is together: whole cluster blaufrankisch floated in direct-press riesling, with soupy destemmed blaufrankisch and grüner added in, all pressed off after fermentation finished (2 weeks) and aged for a year in barrel before bottling. In Moravia, this would traditionally be called ryšák, ‘ginger’ or redheaded wine.

Nadja fell in love with Andrej while working in a natural wine bar in Copenhagan, and moved to Slovakia with him to make wine; they live and farm about fifteen minutes outside of Bratislava, in the Little Carpathians. They made their first vintage in 2019 — this is just year four!

What about regular wine?

Here’s a quick refresh on the norms that our wines deviate from:

To make white wine, you press grapes of any color (but usually green and gold) and let the clear juice run off into a different container. It ferments, you maybe move the fermented juice after it settles, and you keep it somewhere until you bottle it.

To make red wine, you smush up purple and blue grapes and steep the skins and maybe stems with the clear juice, like making tea. Just like tea, the juice changes color — and also changes texture and aromatics. As fermentation starts bubbling and frothing and fizzing, it pushes those skins (and maybe stems) up to the top, forming a thick cap that you can push back down into the fermenting juice to extract more color (and texture, and aromatics).

After a couple of weeks to a couple of months, fermentation is probably finished, and you’ll drain the fermentation vessel and press off the rest of the wine, leaving it to hang out in a different container until you bottle, usually after winter.

Rosé is weak tea made with purple and blue grapes.

Orange wine is tea made with green and gold grapes. It can be weak (made like rosé) or strong (made like red wine), but it’s a little more colorful than the clear juice we call “white wine.”

Further reading on color: ‘A gnostic history of wine color‘ Disgorgeous Zine Winter 2021