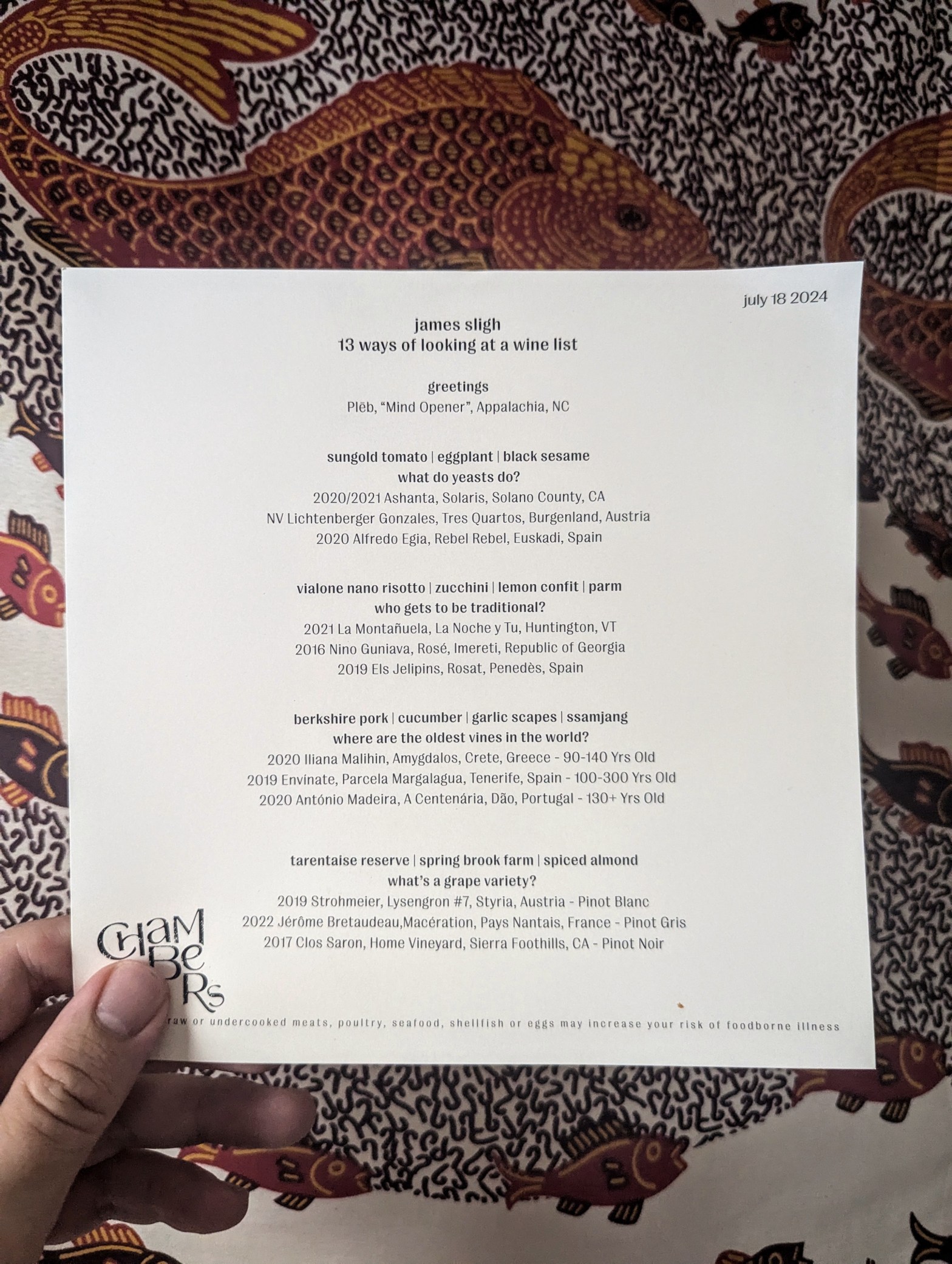

A dinner featuring 13 wines hosted at Chambers in TriBeCa on Thursday, July 18 2024. Below, you’ll find a picture of the lineup, as well as some notes on what we tasted. Here’s what I wrote to set the theme up:

“Working with a cellar like the one at Chambers is a lot of fun. There are truffled-out gems, and classics presented with a point of view, and bottles allowed to acquire some age and wisdom before being served.

“The animating ethos that pulls me in, though, is deeper: curiosity.

“What, this list seems to ask, does the world of wine look like *right now*? How did it get this way? What are the wines that everybody today agrees have ‘always been great’, and how recently were they overlooked as oddballs and trifles? What does wine’s future look like? Where is it coming from?

“What would you like to drink that you’ve never had before, or didn’t know existed?

“In that spirit, we’ll be having dinner with 13 wines from the Chambers cellar organized around a set of questions that seek to unfold wine’s past and future, to provoke exploration, and to reward your curiosity.”

– J”

greetings

PLEB, “Mind Opener”, Appalachia, NC

~ o p e n y o u r m i n d ~

Chris Denesha lives and farms about two hours outside of Asheville, cultivating hybrids on their own roots without synthetic sprays, and employing cellar methods (solera blending, long lees contact, aging under flor) that are pretty classic for marginal climates.

(Some of the other stuff they do, like fermenting a wine in pots made out of the same clay the vines grow in, or kegging three-quarters of their production to save on bottle glass, or making a co-ferment on foraged hickory shag bark, might be a little more esoteric!)

“Mind Opener” is what would happen if you made avant-garde grower champagne out of American hybrids aged on the lees for ~5 years. (And if your liquor de tirage was hickory shag bark brandy.)

Appalachia might be an unfamiliar place for ambitious winegrowing for many of us. But it’s not without deep roots. It’s home to multiple native vine species, and it’s here that a wild hybrid named catawba was found in the woods fifteen minutes outside of Asheville. Catawba was, pre-1860, the variety at the center of the United States wine industry—and the most-planted wine grape in the country.

what do yeasts do?

ASHANTA, french colombard / chenin, “Solaris”, Solano County 2020/21

LICHTENBERGER GONZALEZ, welschriesling, “Tres Quartos”, Burgenland NV

ALFREDO EGIA, hondurrabi zerratia + izkiriota txitxia, “Rebel Rebel”, Bizkaia 2020

A flight about what yeast does to wine after fermentation ends, through three wines that play with reduction, lees contact, and aging under the veil.

“Solaris” unites Ashanta’s first vintage, made at Tony Coturri’s place, with their second: two workhorse white varieties from a workhorse vineyard in a workhorse wine region: Solano County’s Green Valley, west of Fairfield, tempered by morning fog and cooling breezes from the San Pablo Bay. The French colombard was aged without topping up until it developed flor, three months in; the following year, the baby solera was refreshed with more colombard, and bottled after blending with some fresh chenin from the same site. A streak of bright acidity on the finish snapped together with the sungold tomatoes on our plate.

In Burgenland, curled around the second-largest lake in Europe, a giant shallow reed-filled pond called the Neusidl, Martin Lichtenberger and Ariana Gonzalez have a single barrel of welschriesling that develops flor. They leave it untouched for two years; the portion that remains is bottled as “Tres Quartos” (three quarters). The most delicate, filagreed, and lifted of the flight, with a saltiness all three wines shared.

Finally, a half hour southwest of where I lived in Bilbao, in the green hills just before Basque Country gives way to Castilla y León, we have two grapes native to this stretch of the Atlantic Coast: hondurrabi zerratia and izkiriota txitxia (or petit corbu and petit manseng, if you cross the border). “Rebel Rebel” ferments and ages them on their gross lees without racking, with some barrels left untopped and exposed to air. Alfredo Egia apprenticed with Richard Leroy, among others. The wine has a lot in common with Leroy’s chenins on schist — but also, geographically and spiritually, with someone like Arretxea (in Irrouleguy, on the other side of the border) in its power, texture, and savory balance of reduction. There was a black sesame mayo with our sungold tomatoes and eggplant — this was perfect with it.

who gets to be traditional?

LA MONTAÑUELA, co-fermented field blend, “La Noche y Tu”, Vermont 2021

NINO GUNIAVA, mgabolishvili rosé, “Rosé”, Imereti 2016

ELS JELIPINS, sumoll + macabeo co-ferment, “Rosat”, Penedès 2019

How have regional identities been reshaped by money and time? What do people picture when they picture traditional wine? Who do they picture safeguarding that tradition? This flight walked and chewed gum at the same time between style and ethos: a set of wines interrogating the notion of tradition and typicity, all made by women, all incidentally on the rosé and co-ferment spectrum.

Until somewhere between the 16th and 19th century in most places, vineyards were usually planted to crowds of varieties: red, white, and pink together. Wines made from them were fermented together, too, rose gold and copper and partridge’s eye and onion skin. (For a contemporary version of this in a classic wine region, look at Julien Guillot’s homage to 10th-century Burgundy, “Cuvée 910”.)

“La Noche y Tu” is from an organically-farmed vineyard planted in Huntington in 2006. The wine blends a slew of Minnesota cold-hardy hybrids harvested successively over the course of September and October: foot-crushed frontenac gris and la crescent, destemmed & pressed marquette, petit pearl, and frontenac noir. Camilla Carillo, one of the constellation of protegees who have come out of La Garagista in Vermont, made her first vintage in 2018. Deeply hued (frontenac is red-fleshed), the wine is a juicy welterweight that belies its color in the glass, with a plum-skin, alpine edginess and a kaleidoscope of wild berry and herbal aromatics.

Nino’s 2016 Rosé is made from mgaloblishvili, one of the hundreds of Georgian native varieties almost lost during the 20th century, when Soviet rationalization of the country’s viticulture pruned away cultivars not tagged as regionally important. Nino’s father, Archil, can remember his grandfather tending 100 year-old mgaloblishvili vines before they were uprooted. She’s made restoring the variety her project, planting a thousand nursery cuttings and making her own wine from them in his cellar.

We’re in Imereti, western Georgia, on the other side of the mountain spine that cuts the country in half, where the air changes from hot and dry to mild, damp, subtropical: you feel the breeze from the Black Sea, vines are trained in pergola to ward off fungal disease, and local varieties and winemaking traditions tend towards fresher, lighter, and more lifted.

Most Georgian qvevri wines come into the market the year after harvest, out of necessity. Tiny producers don’t have the space to cellar last year’s wines, or the cash flow to sit rather than sell. Despite ancestral practices that echo our earliest archeological traces of winemaking (buried clay, a degree of skin maceration), the contemporary commercial reality is quite recent. Qvevri wine had become almost extinct over the course of the 20th century, preserved by home winemakers in rural villages.

It’s only been in the years following the 2006 Russian embargo of Georgian wine and subsequent invasion (Russia was the destination for 90% of the country’s wine exports) that the scene has come back to life, bottling wines and sending them across oceans. Before the embargo, there were around 80 registered wineries in the country. Less than a decade and a half after invasion, that had bloomed into thousands. Today, the people making them aren’t just the stubborn old village uncles who’d carried the torch for qvevri wine. They’re folks with university degrees moving out from the capital, foreigners and the newly arrived, mothers, sisters, daughters.

This is a long way of saying that to be able to serve one of Nino’s first (her very first?) vintages, 2016, was both a rare privilege—wine like this wasn’t being bottled at all eight years before it was made; women like Nino weren’t really making qvevri wine before this moment; getting to taste something from Imereti aged eight years further is unheard of—and a source of a little stress: how had it developed, this qvevri-aged rosé of a lost and found grape?

A little miraculous, is the answer, and I shouldn’t have worried: silky, color evolved to blood orange or bronze, umami-laded (wood beech mushrooms or white miso), perfumed. It was the wine of the night I that I had the least idea of, in terms of how it’d be behaving. For Oliviero, the sommelier at Chambers, it was simply the wine of the night.

As a counterpoint to both Nino’s Imeretian qvevri rosé and Camila’s co-ferment, the flight concluded with 2019 Rosat from Els Jelipins, deep in the interior hills of Font-Rubí, rising off the valley floor of Penedès in Catalunya. Penedès is a region reshaped by the big business of commercial viticulture and globally recognizable wine style: ‘cava country‘.

While cava country is overwhelmingly planted to wall-to-wall vines—the white grapes of cava, xarello and macabeo and parellada and a little chardonnay for good measure—the region’s pre-20th century past was polycultural, with the grape part of ‘poly’ dominated by red varieties like the one in this wine (and is not allowed in the Cava D.O.): brooding, intransigent sumoll.

Glòria Garriga and her daughter Berta work with a scattering of miniscule plots—abandoned ancient vines, a couple local growers, small young plantings on different hillsides as experiments. It’s an evolving practice, and certainly more complicated in terms of where the grapes are coming from and what they are than the importer tech sheets state. But as far as I can tell, the core of their rosé is a co-planted, centenarian vineyard of sumoll and white macabeo fermented together and aged in beeswax-lined terracotta amphora. (The amphora are smaller than Georgian qvevri, 300 or so liters against the almost 2,000 that the person-sized, buried qvevri, each handmade and slightly differently-sized, can be.)

The wine is the easiest-going and most immediately accessible of Els Jelipins’ famously intense, knotty wines, but it’s still solar, savory, and uncoiling after five years of bottle age.

where are the world’s oldest vines?

ILIANA MALIHIN, 90-140 yr old vidiano, “Amygdalos”, Crete 2020

ENVÍNATE, 100-300 yr old field blend, “Margalagua”, Tenerife 2019

ANTÓNIO MADEIRA, 130+ year-old field blend, “A Centenária”, Däo 2020

The question, ‘Where are the world’s oldest vines?’ has a couple of depressingly simple answers.

One is, ‘Where didn’t phylloxera find you?’ Anything older than a century or so had to have been somewhere that the louse didn’t penetrate during its unstoppable spread from 1860 onward, either because of broader geographical isolation or because of local soils. (Phylloxera has a hard time getting through sand and slate. Testifying to this, for example, are the numerous pockets of pre-phylloxera riesling plots in the oldest slate terraces of the Mosel, or in the sands of Collares or .)

The second—maybe even more important—is, ‘Where didn’t capitalism find you?’

Old vines grow overwhelmingly in places where poverty and lack of attention have allowed their survival. Places with ongoing access to capital and markets for their wines have the incentive to successively replant to keep productivity up. Old vines can’t make enough grapes to hang. The average ‘quality’ age they’re looking for in, say, Bordeaux is something like 35 years old. The energy is very Logan’s Run.

It’s a funny situation in which ‘old vine’ is glamorized and fetishized by wine geeks and sommeliers but has an inverse relationship with the blue-chip wine regions they tend to admire.

Iliana Mahilin’s “Amygdalos” is made up of scattered 90- to 140-year-old highland plots of a white grape indigenous to Crete: intense, oily, with a Mediterranean herbal-cedary-sweet herbal dimension and salty, driven finish. Her first vintage was in 2019 after growing up in Crete and working with old assyrtiko vines on Santorini. The 2022 August wildfires that swept the island damaged many centenarian vines, and while she’s been planting cuttings as well as working to rehabilitate them, I haven’t seen definite word yet whether or not they’ll recover. (A similar tragedy struck the ancient vines of Itata after intense wildfires in 2023.)

“Parcela Margalagua“, on the northernwestern tip of the volcanic island of Tenerife, is a field-planted plot on steep red basalt that plunges into the Atlantic—at the times these vines were planted, 100-300 years ago, straight into port, where ships waited to receive wines fermented and raised in cask up in the vineyards. The melange of varieties — baboso, malvasia negra, negramoll, listan negro, listan prieto, and more—sprawl untrained and wild on the ground, are harvested at the same time and co-fermented with whole clusters and little extraction. The wines are always intensely smoky and savory, with a briny quality of reduction that can be off-putting especially when the wines are young. (And Envínate makes so little of these single parcel Canary Islands reds that very few restaurants or bars have the wherewithal to keep them and see what they’ll do.) Getting to pull a bottle of this from 2019 and see it start to relax a little bit was a treat.

Finally, Antonio Madeira’s “A Centenária” was something I’d heard about but not gotten the chance to try until the dinner. Many of the genetics of the old vines in Margalagua date to the Portuguese colonization of the islands, which was happening in tandem (and competition) with the Spanish until the Pope divided the known world.

Here, in a single site the size of 7 tennis courts, is a kind of Atlantic counterpart to Envínate: at least forty different varieties (including jaen aka mencía) planted sometime in the 19th century on the high-elevation granite plateaus that define the Dao as a region, at a time when it was important to an international wine trade. Deeply colored, there was a paradoxical lightness and space here too between the structure. (2020 was a difficult frost vintage, with a desperate concentration Antonio’s wines don’t always have). The finish was on the salt and olive brine, a bracing and savory spine.

what’s a grape variety?

STROHMEIER, pinot (blanc), “Lysegrøn #7”, Steiermark 2019

JÉRÔME BRETAUDEAU, pinot (gris), “Macération”, Pays Nantais 2022

CLOS SARON, pinot (noir), “Home”, Sierra Foothills 2017

The further back you go, the less it was ever about a vineyard planted to a single grape variety, let alone identical clones of a single instance of that grape. As modern drinkers, though, we’re locked in to variety as signifier, not just of the character and quality of a wine itself, but for what it says about us, our taste and discernment and sense of ourselves.

Pinot is one of my favorite ways to have my cake and eat it too, given the irreversable supremacy of variety. Pinot ends us on comfort and classicism with our cheese course. But pinot is also ancient and varied enough that between its range of mutation and geographical dispersal you can still have the weird wide world at your feet.

Franz Strohmeier’s Lysegrøn is one of the wines that helped unlock, for me, the sometimes confounding minimalism of pinot blanc, its quiet insistence on texture, the difficulty of saying when less is more and when less is just … boring?

We’re in the green sub-Alpine garden of Austria’s Steiermark, with its pumpkin seed oil and white asparagus and river gorges, a place notable for: electric rosé and light red made from a local schnitzel grape, blauer wildbacher; a regional stamp on sauvignon blanc that makes it taste like nowhere else on earth (delicious); and a growing number of tiny growers planting no-spray PiWi hybrids and making wines that kinda taste like this. (Strohmeier among them.)

Quiet moonlit pools, texture, more aromatic intensity along the dill flower – acacia blossom – dogwood – crab apple than you might expect—and bottle age, which Franz’s wines handle beautifully. (File, if you’d like, alongside a thousand other examples of no-sulfur wines that achieve classical purity over time.)

Pinot gris, despite a commercial identity as the vodka-soda of grocery store wine, plays a kind of prankster-y chameleon counterpart to pinot blanc’s wallflower if you’ll just let it. Bretaudeau’s “Macération” is a great example of this: destemmed, fermented with the skins, aged in an eclectic mix of concrete and clay and wood, the wine is the deep coppery-pink that is my favorite coat pinot gris owns. The approach to extraction here is really gentle and precise—instead of tannin there’s just a hallucinatory depth of fruit and midpalate weight, as though it’s been concentrated and hung in aspic.

Finally, Gideon at Clos Saron made some of the first wines that overturned my baby restaurant professional’s received ideas about what ‘California wine’ was in the grand scheme of things, and scrambled what I was being taught back in 2011 or so about the old and new world.

We’re in the Sierra Foothills, which during the Gold Rush became the most important winegrowing region in California until it faded into post-Prohibition obscurity. As a place to find high-elevation intensity, the collision of diverse soils, and eccentrics far enough from the center to work within stylistic bounds they set for themselves, it’s maybe the region that excites me most in the (very big, very varied) state.

The 2017 Home Vineyard comes from two and a half acres across a 1600ft elevation clay-loam slope over volcanic ash, granite and quartz, planted in 1979 and 1999 to as many different cuttings of pinot as they could get, plus a handful of pinot gris and chardonnay vines. (Even this, in the end, wasn’t a single-variety wine.) It was showing beautifully, and it made me happy. No notes.