An afternoon tasting series exploring how wine gets the way that it is and the ways that we talk about it, hosted in the backyard Pool installation of Hi-Note, a radio listening bar in the East Village.

[The next class will be on Sunday, September 8]

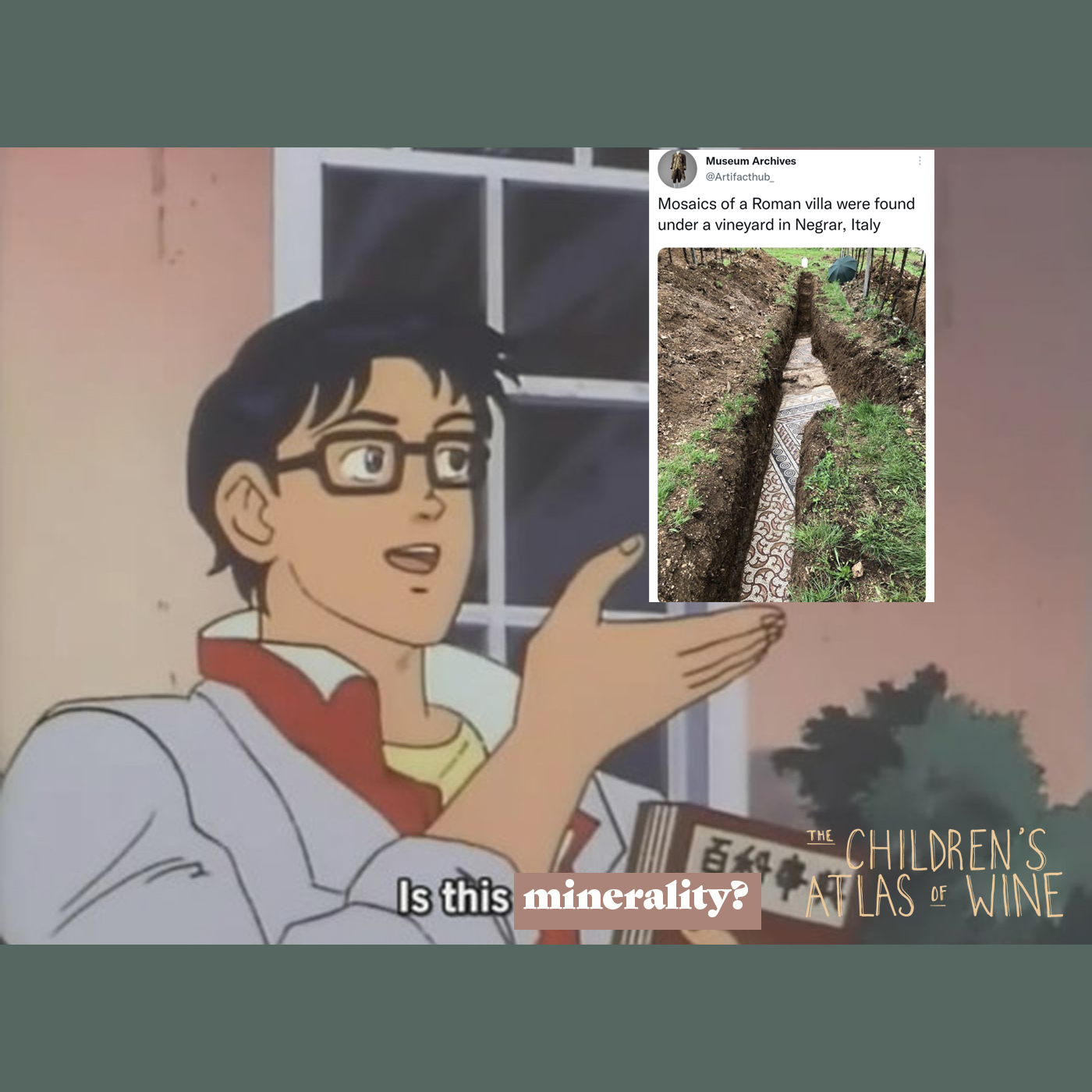

What does it mean for a wine to have “minerality”? What difference does it make to be grown on sand or clay? What about the bedrock beneath the soil?

We tasted five wines to begin untangling these knots. You can read more about what we drank, and the questions we asked while we did, below:

“Mineral – y white”

JOCHEN BEURER, sylvaner, “Alte Reben” WÜRTTEMBERG

A bright, green laser beam of acidity to cut through a muggy day; an absence of perfume and honey; a textural prickle that feels crystalline; a saltiness.

All of these came up when asked what you might expect if you asked for a “mineral-y white” at a bar or in a store. We talked about shades of meaning, the way that for some tasters “has minerality” might imply something like “has dimension / energy / quality”—an aesthetic category beyond fruit salad or beverage.

We talked about the mineral salts in spring water, and about the tiny .5 to 1.7% pile of material left if you were to burn away the water and alcohol in a glass of wine. We talked about intensity — did wines with minerality have more going on, like Vichy Catalan, or less, like seltzer?

If we asked for a mineral-y white and got this, Jochen Beurer’s old-vine sylvaner from the sandstone & quartz on the heights of the Kieselsandstein, bottled unfiltered after a year and a half settling clear in old barrel, would we be happy?

Yes, we agreed.

But minerality opens a door beyond style, too — more than salt and acidity, it poses the question, “Can you taste the rocks a vine was grown on?”

“Same place / Same grape / Different rocks”

LISE & BERTRAND JOUSSET, chenin on limestone, “Premier Rendezvous” MONTLOUIS

BENOIT COURAULT, chenin on schist, “Gilbourg” ANJOU

The heart of the Loire is a good spot to explore this question: a place where the warm Gulf Stream is funneled deep into continental France by the last wild river in Europe, where climate is broadly similar — able to ripen late-ripening varieties like cabernet franc and chenin — but split in two by geology.

To the west, metamorphic blue-black schist in Anjou, legacy of long-extinct volcanoes; to the right, in Saumur and further east of Tours, creamy yellow tuffeau limestone, the floor of 75 million year-old shallow tropical seas.

Geologists are not fond of the idea that vine roots interact with bedrock. (“Roots don’t suck up minerals like a straw!” they’re always telling me. “Rocks don’t smell until they’re degraded organically!” they yell. “You can’t taste limestone!”)

Here are two chenins from the same vintage, made (broadly speaking) the same way. Both are assembled from a scattering of parcels.

The Jousset’s is from around the edge of their oldest plots on the little ridge of Montlouis’ Grand Côte, clayey soils carrying globules of flint over limestone.

Ben’s is from plots around his cellar in the hamlet of Faye d’Anjou, on the slope overlooking the little trickle of the Layon tributary, over a local schist called ‘gréseux de Saint George’ with veins of silica and quartz.

One is broad, phenolic to the point of tannic structure, like the skin of a pear, with a density and a tonic-water bitterness and a smoky-savory edge of the aromatics. [1]

Another: leaner and more lifted, with a delicate honey and coconut feel and a long, persistent salt-lick core on the finish. [2]

Can you guess which is chenin on schist, and which is chenin on limestone?

(Spoilers at the links above.)

And if geologists aren’t fond of the idea that you can taste rocks, what explains the fact that many people who taste a lot of wine, experientially, can and do?

We’re not going to litigate this to conclusion in a class recap, but I have three ideas to propose.

One: bedrock matters even if we limit ourselves to what happens after you pick the grapes.

Porous and soft, the limestone around Montlouis and Saumur has historically meant natural caves expanded by human activity—useful for occult ceremonies, bomb shelters, and fermentation. Naturally temperature controlled storage meant they went low, slow, and cool; sometimes, it could even block malolactic.

Schist, meanwhile, was too hard to dig basements out of. Ferments happened hot and fast, above ground, malo done, on grapes riper because of heat absorbed by the darker soils.

Two: even setting aside the obvious implications of soil pH and drainage, roots do commune — indirectly — with the bedrock beneath those soils, as long as you’re farming a living microbiome and not treating it like a hydroponic growth medium. If you take a microscope to the bedrock, you can literally see tunnels bored by microorganisms that convert inorganic minerals into nutrients accessible to the plant, roots corseted by mycorrhizal fungi.

Almost everything in a grape comes from water and sunlight—free energy stripped from electrons via photosynthesis. But some of that little pile of dry extract that remains when you boil everything away has to do with nutrients accessed by the plant itself, and soil microbiology is a complex and expanding field of study that is outside of our geologist’s area of expertise.

Three: there may be a misunderstanding here that’s fundamentally linguistic. What is “tastes like limestone” if not a metonymic shorthand for a inarticulable energy shared due to a complex, indirect whirl of causes among a hundred wines that have limestone as a bedrock in common?

“Same place / Same rocks / Different grapes”

FACE B, macabeu, “Makeba” ROUSSILLON

FOULARDS ROUGE, carignan, “Vilains” ROUSSILLON

How to start building a corpus, a common language, a metonymic shorthand?

Only one way: taste a lot of wine.

Here are two more of them:

“Makeba” is macabeu on schist planted in 1964 and farmed by Séverin Barioz and Mathilde Ceccon outside of the village of Calce, in the Roussillon. We’re in mountain-building country, in the Agly river valley in the foothills of the Pyrenees, where geological cake layers have been thrown on their side and shattered. Calce, named for the chalk limestone in the hills around it, also has plots on metamorphic rock scattered around it — one of the rare places in the world of wine where the dark and light sides of the moon, limestone and schist, are pressed together.

“Vilains” is a different flavor of metamorphic: decomposed sandy granite and gneiss off the mountains and approaching the sea, inland of Banyuls-sur-Mar, the ancient port tucked into a fist of black schist just before you hit the border. It’s a single plot of old-vine carignan, left in whole clusters for two weeks to ferment gently and then blended after the press — slightly fizzy, fresher than you’d expect.

Does “Vilains” taste like sand and granite? Does “Makeba” taste like schist? Do they have anything in common with “Gilbourg”, a world away in Anjou?

Armed now with some things to look for and some questions to ask, we can continue exploring . . .

One thought on “TASTING GROUP: ‘Soil’”