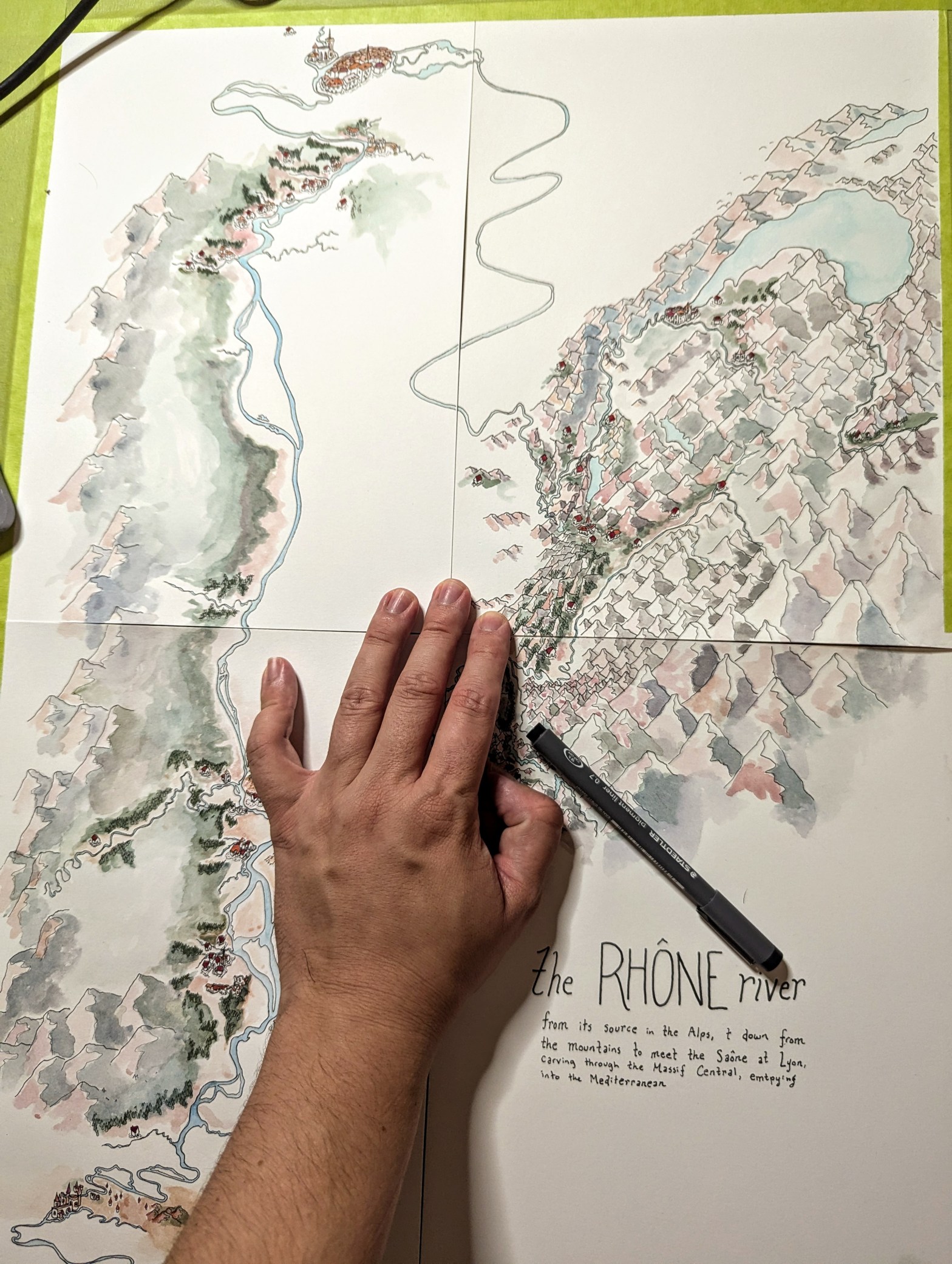

It’s a new map!

Available in four different sizes and prices: fine-art giclées in original (18×24″) and slightly smaller (13×19″) sizes with archival inks and cotton rag watercolor paper suitable for framing, as well as more affordable posters (12×18″ and mini 8×12″) digitally printed on tagboard, for shops or educators looking for study guides, bedroom decoration, and something that can take a syrah stain.

Orders (available here) include shipping. Please allow 2-3 weeks for production and delivery.

Rivers invite continuity. They flow, they rush, they ask us to go tubing from one place to another.

We could, of course, chop everything into discrete chunks.

We could slice them, thinner and thinner, until the smallest unit possible spins in a vacuum for our consideration. We could study the climats of Hermitage without any reference to the same grapes on the other side of the river around Tournon — to say nothing of the grenache overlooking Tavel, or the gamay overlooking Lyon.

My old edition of the World Atlas of Wine has what I remember as an entire half page devoted to Hermitage’s climat differences, thirteen different named sections of a south-facing hillside planted wall to wall to about 140 hectares of vines, the majority split between one iconic grower (Chave), two merchant houses, and the co-op. The wines from there are, historically, very famous, to the point where they were habitually blended into 19th century Bordeaux to fortify it. They’re benchmarks for entire generations of well-heeled connoisseur Englishmen.

(And so, the dutiful student memorizes the attributes of wines they will never try and that barely exist, in that most bottles are blends of different sites anyway: the climats of Beaume and l’Hermite, on the top of the hill near the little chapel, are “the lightest, most aromatic red[s]”; Péléat is “relatively fleshy”, Les Gréffieux “elegant, aromatic”, Le Méal “extremely dense, powerful”, Bessards “tannic, longest-lived”…)

Nothing wrong with this, I guess — but equally true and useful in coming to grips with how things are, as an alternative to infinite tiny chopping, is the smeary spectrum of likeness we can draw as we rush past granite massifs and sedimentary plains, from glacial water in the Alps to a delta in the Mediterranean.

It’s family reunion picture time for all of the vines the river connect: everybody’s got the same nose.

The little ones — persan, etraire, gamay — running around in the back yard. Mondeuse giving fist bumps to syrah — they always looked up to their older cousin. Roussanne getting their nails done in Chignin.

All the reds are wearing grillmaster aprons, all the whites are kinda like potato salad.

Does it take some discrete warping of time and space to bend the mountains towards the sea on four 9×12″ panels, to pull things closer and press them together rather them pick them apart?

I wouldn’t use it for driving directions, is what I’ll say.

But I think you can see the way that the valleys in the Alps that see the sun are like a chain of islands; the roasted slopes around Ampuis and Vérenay; Hermitage’s south-facing hill; how much I love Cornas because of how many growers I love that make it; the way that the Isère is the lost connective tissue between the mountains and the delta…

You can listen to me talk about this a little more on the first episode of Disgorgeous’ Rhône season here. More about the middle of the Rhône itself, sometimes called ‘northern’, here — along with a map I drew before the pandemic. More below, as I keep fiddling with this, infinitely ___________ :

A list of all of the growers labeled on the map

NB any checkeable facts come from public importer or producer websites, anything else is from the soup in my brain that comes from working service for a decade

VALAIS

wide, glacial valley carved by the Rhône, sun-drenched and in the shadows of the Alps; look for lots of chasselas, mountain specialties like petit arvine and cornaline and humagne rouge, savagnin (called heïda), as well as gamay and syrah — if you can find any of it. Swiss wine is mostly drunk by the Swiss, and very little sloshes out into the export market.

Cave Caloz old-school organic grower active since the ’60s, classic Rosenthal Swiss portfolio vibes

J-R Germanier organic, one of the oldest active Swiss commercial wineries (19th c), see above. (we tasted bottles from both of these on my Disgorgeous episode)

Ô Fâya Farm brand new (first vintage 2019), looser/more playful in style, also farms apricots and keeps goats, set up the winery via a crowdfunding campaign (new to the NY market this year, I sell these wines via Roni Select)

SAVOIE

Vignes de Paradis the part of the Savoie that looks like it should be in Switzerland. guy has a concrete pyramid he built himself for aging wine, among other vessels in many shapes.

Brasserie Voirons farmhouse ale brewery that makes a series of “bière vivants” aged on the wine lees from iconic French natural winemakers, including gringet lees from Belluard, below

Belluard Dominique was an icon who, tragically, passed in 2021. A big part of his work was dedicated to an almost extinct grape of his village, gringet; his estate is now being worked, as Domaine de Gringet, by a young successor who took over with the blessing of his widow.

Jean-Yves Péron wild guy, one of the first whackadoodle natural wines I’d ever tasted from this part of the world back when I was a baby somm. obsessed with the macerated whites of northeastern Italy, now makes a bunch of stuff with fruit purchased from the other side of the Alps, e.g. grignolino, skin-contact moscato

des Ardoisières a narrow valley with abandoned vineyards and crumbling terraces cleared and replanted above the village of Cevins in 1998 and originally made by retired legend Michel Grisard, eventually turned into a going concern under his successor Brice Omont. some notably rare varieties including persan and mondeuse blanche. bottlings named for geology (“Quartz”, “Amythyste”, “Schiste”). there are some other young vines way across the region in St Pierre de Soucy.

Louis Magnin old school quality with a capital Q, the sort of grower that leads wine writers to sentences like “he rises to the top like the richest cream”. Biodynamically farmed (since 2010) 8 hectare estate started in 1973 that eschews jacquère entirely to focus on mondeuse with a minor in bergeron (roussanne) and altesse, kind of a mini-northern Rhône structure. One of those guys that for many years was one of the very few growers doing that kind of work in their region, and as such got treated as sui generis; influential.

l’Aïtonnement named for the village, Aiton, whose wines, steep-sloped and prized, disappeared into obscurity after phylloxera, unable to be worked with mechanized tractors, too hard to farm. Maxime Dancoine joined two local farmers in 2016—the last vignerons in Aiton—after apprenticing with Louis Magnin (above). in addition to mondeuse, he works with a number of rare local cultivars: joubertin, douce noire, mondeuse’s grise and blanc mutations… wines are light-touch but wear their ambitions on their sleeve

Adrien Berlioz a last name you’ll see all over the place here

Mathieu Appfel newer, wilder, looser

Côtes Rousses

Dupasquier

BUGEY

Marie et Florian Curtet

Les Cortis

des Éclaz

Yves Duport

Renardat-Fâche

ISÈRE

des Rutissons

Finot

Jérémy Bricka

Nicholas Gonin

LYON ish

Eric Texier

CÔTE RÔTIE & CONDRIEU

Jamet

Champet

Levet

Jean-Michel Stéphan

Stéphane Otheguy

Bénetiere

Thibaud Capallaro

ST JOSEPH & ARDÈCHE

des Amphores

Benoît Roseau

Rouchier

Hervé Souhaut

HERMITAGE / CROZES

Dard & Ribo

J.-L. Chave

Pierre Gonon

Alain Guillot

David Reynaud

CORNAS & ST PÉRAY

Mathieu Barret

Cyril Courvoisier

Mickaël Bourg

Allemand

Marcel Juge

Balthazar

One thought on “Map Print: the Rhône river”