This post was originally sent out as a free newsletter in December. Join the mailing list here.

What does it mean to make a list of ten wines at the end of a year?

From a certain vantage—maybe, like, a Bon Appetit listacle?— I imagine it’s more trendspotting than anything else. Silky, infusion reds were big this year — you can even chill them! // You won’t believe that THIS place makes wine! // Silvaner is the new Sauvignon Blanc!

For a different person, often a working sommelier or a business owner, it’s an aesthetic flex: here is my discerning eye, here is my exquisite taste. (There are many flavors of this, from boutique importers to consultants to beverage directors, but somewhere deep in the mix there’s usually a sale to be made: drink off of my list, or out of my portfolio, or from my store shelf — and don’t forget to slam that ‘like’ and subscribe…)

For some writers, it’s more like basic service journalism. Longtime Times critic Eric Asimov built his 2024 list, not from his oldest and rarest, but around bottles like Martin Texier’s “Brezême”, Bow & Arrow’s chenin, and Enric Soler’s Catalan whites, a big-platform version of what you’d get from a “these are our staff’s favorite wines” at a neighborhood retailer. Current-vintage new classics that will feel fresh and surprising to the paper’s national readership, and give a little boost to the indie wine stores and distributors who can repost that validating screenshot.

At this point, a few of you, at least, are getting impatient with me. Why am I making it so complicated, as usual? A top-ten list of wines of the year should be a list of the year’s BEST WINES you drank, duh.

And oh boy, with that box opened: what, do we think, does ‘best’ mean?

What makes a wine great? What even makes a wine good?

Is a list of the greatest wines you tasted in a year and the list of the wines you liked the most going to be the same list?

What does it mean to like something?

Here’s where I end up, when sitting down to make these. It’ll be the end of the year, which means I’ll be on the last leg of the most hectic, grinding season for pouring wine, selling bottles, running cardboard tubes full of art to the post office, whatever I happen to be doing to try to make rent, and I’ll be fighting for my life. The days will be as short and dark as they’re going to be.

I’ll scroll through my camera roll — was that night in January really still thisyear? — trying desperately to rekindle the feeling of being moved by a bottle of wine, of feeling lit up by electricity and anticipation or feeling the noise in a room fade for a moment and a bubble of calm settle.

A little piece of John Berger will pop into my head, from his 1985 essay ‘The White Bird‘: “The problem is,” he writes, “that you can’t talk about aesthetics without talking about the principle of hope and the existence of evil.”

And then, because I’ll worry that this is obtuse out of context, I’ll sit down and reread ‘The White Bird’ two more times.

Then I’ll copy out about a third of it into the body of the newsletter before deleting it, since it’s begun to overwhelm the text, feeling as I do so that, nonetheless, there’s something inherently wine-like about the folk art object Berger hangs his piece on, a repetitive series of small variations on a theme, two pieces of pine wood carved and held together with a single nail, whose success lies in “a respect for the materials used”—the wood’s “own qualities of lightness, pliability and texture”—and which “provokes at least a momentary sense of being before a mystery.”

How? “One is looking at a piece of wood that has become a bird. One is looking at a bird that is somehow more than a bird. One is looking at something that has been worked with a mysterious skill and a kind of love.”

“In any case,” Berger writes further on, “we live in a world of suffering in which evil is rampant…a world that has to be resisted. It is in this situation that aesthetic moment offers hope.

“That we find a crystal or a poppy beautiful means that we are less alone, that we are more deeply inserted into existence than the course of a single life would lead us to believe.”

So we can have an aesthetic moment in nature, and with art, even when that art is a little white pine bird hanging from a thread, and what’s the difference?

“The white bird is an attempt to translate a message received from a real bird. … Art does not imitate nature. It imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature. Art is an organized response to what nature allows us to glimpse occasionally.

“Art seeks out to transform that potential recognition into an unceasing one.”

So here’s what we have:

Ten wines I drank this year, out of many wines I drank this year, in chronological order. They were wines shared with people I love; opened in places and contexts that ladled on meaning. They were wines that made me feel things: joy, or relief, or celebration, or comfort. They were, themselves, wines that carried meaning my way, wines that bore history and context: fermented in containers that have since cracked, made by people no longer with us, wearing mourning bands.

They are not the only wines I drank that I cared about, or thought were delicious, or that I think you should buy or pay attention to.

But they are ten bottles that encompass one version of this past year for me, before we knew exactly how bad it was going to get, and after it had become quite clear.

Berger finishes where he began:

“The white wooden bird is wafted by the warm air rising from the stove in the kitchen where the neighbors are drinking.

“Outside, in minus 25° C, the real birds are freezing to death!”

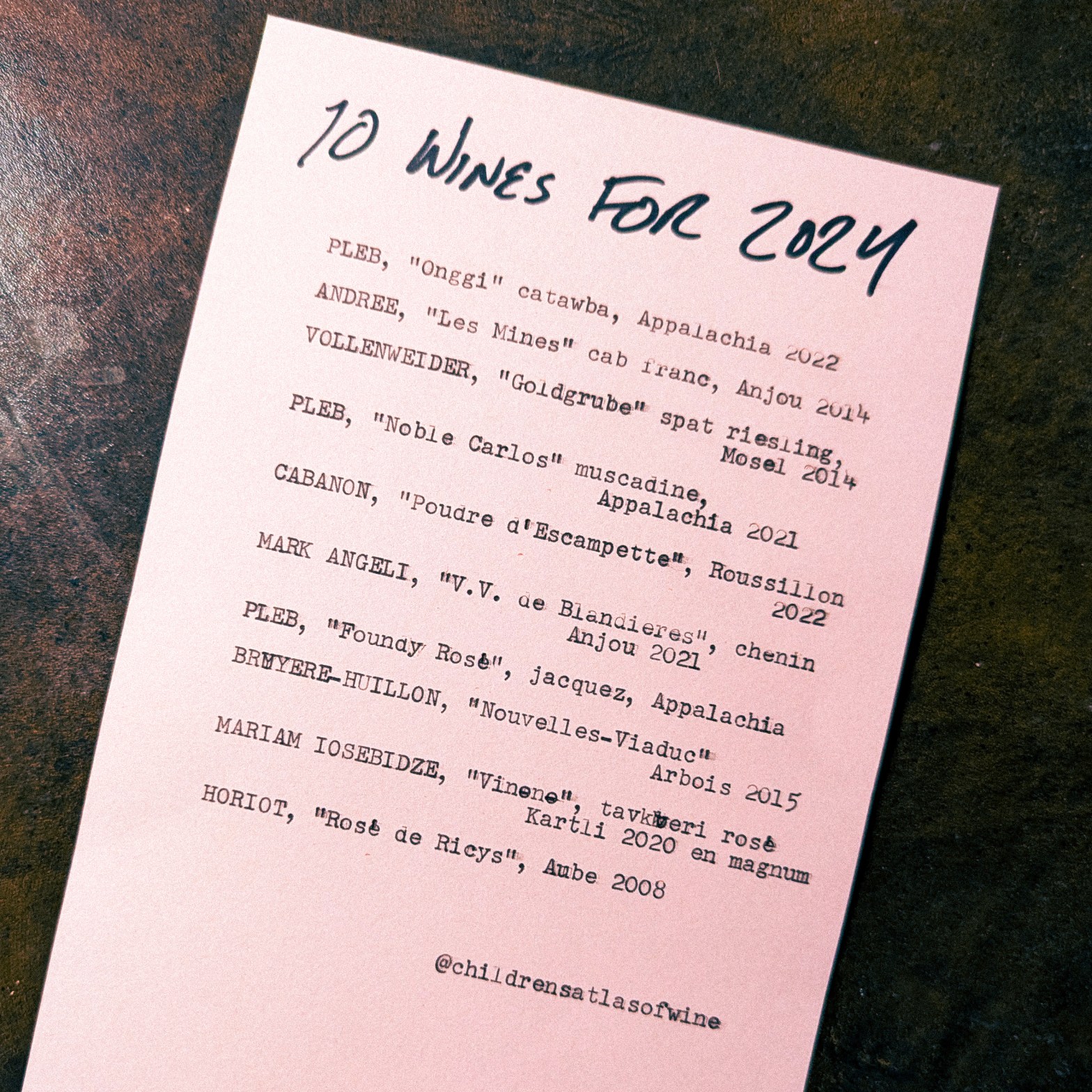

PLĒB ‘Onggi’ skin-contact catawba Appalachia 2022

A white whale for me: the first vintage of wines aged in onggi made by a Montana-based potter out of North Carolina red clay. It’d taken three years for Pleb to get the pots, what with pandemic delays, and they were small for clay vessels used in wine: this one would have been about 50 liters. (Compare to upwards of 2,000 liters for the biggest Georgian qvevris.)

They made 72 bottles. They made it out of catawba, a grape born wild in the woods a fifteen minute drive outside of Asheville, hand destemmed and fermented whole berry for a month, aged in a container made out of the same soils it’d grown in.

With that little made, it was never coming to the wholesale market. But in January, Chris Denesha brought a bottle out to Oakland for the fourth [ABV] Ferments, and shared it at the afterparty. Jagged and watermelon-colored and electric, with catawba’s signature mulberry aromatics and sizzling acid structure.

What a treat, I thought at the time, riding the high of the community and collaboration and wondering and dreaming that the festival embodies — to be able to taste the first trial of an experiment in terroir that was going to last the rest of my life. A little door to the future cracking open.

ANDRÉE ‘Les Mines’ cabernet franc Anjou 2014

In February, an anniversary dinner with my partner drinking wines from the year we’d met, out of the deep cellar uptown at Eli’s Table.

2014 was also the year I got hired at Pearl & Ash and, a few months later, became a wine team cellar rat, one foot down the rabbit hole, and then one whole leg, and then up to my eyeballs.

In retrospect, too, it was the last “classic” vintage in the Loire, for people inclined to talk in such terms. (Even then, it wasn’t classic as in “easy” or “normal”—early flowering, wet summer, and most notably an invasive fruit fly species that punctured thin-skinned red grapes, meaning that it can be a rough one for, say, Jura poulsard or Touraine pineau d’aunis.)

Despite twists and turns in the weather, and a climate that was already fraying at the seams, the wines from ’14 still drink like Goldilocks exemplars, benchmarks of a normalcy that we’ll barely remember in another decade or two — second-term Obama wine. If you’ve been drinking Loire cabernet franc for long enough, ’14s just taste right, and everything else since feels like a state of exception. It’s only when you look up that you remember the state of exception has lasted your entire professional life, with no end in sight.

This was Stéphane Érissé’s fourth vintage of Andrée, a collection of 3.7 hectares of plots scattered across a vein of charcoal crossing the Layon. He’d bought them from a retiring farmer who’d been working them organically since the mid-90s. It’s just at the place where the extinct volcanoes and metamorphic schists of Anjou Noir end, and the buttery yellow limestone and long-ago tropical shallows of Anjou Blanc begins. (The wine is grown on this black rock; it ages in a limestone cavern.)

So many ways to fold and refold time: the decade these wines had been aging, since harvest and bottling. The decade we’d lived, along with these wines, before drinking them.

Stéphane’s wines are composed and lovely in ways that don’t necessarily get a lot of attention relative to his peers. He trained with Cyril at Clos du Rouge Gorge and Charly and Antoine at Clos Rougeard, and between the pedigree and how good the wines are you’d think they’d be cultier. They have a certain understatement to them, like playing a snare with a tea towel to muffle the recoil, but part of the reason he flies under the radar might, simply put, be grief. The wine wears a mourning band: Jade, his daughter.

A vintage is a year in somebody’s life.

VOLLENWEIDER ‘Goldgrube’ spätlese riesling Mosel 2014

Another decade-old bottle, a month later after an overnight train from New York, settled in for a birthday lunch at the Cherry Circle Room in the former Chicago Athletic Association building.

It was the Saturday the weekend before Saint Patrick’s day, which is an absurd time to try to do anything in downtown Chicago. I went to college in Boston; I still retain the capacity to be surprised. After that meal we’d be the only people not wearing green at the Art Institute of Chicago, watching a kind of children’s zombie movie take place on the streets below through the big plate glass windows, drunk kids from the suburbs dodging bicycle cops and circling each other like puppies.

A deeply silly way to settle in to the encompassing comfort of this bottle.

The wine list here — the woodworking is very nice, by the way— looked like it was put together pre-pandemic when they opened, and maybe hasn’t been picked over since because it’s a downtown hotel restaurant, I don’t know. There were a thousand people in glitter top hats playing skee ball on the other side of the double doors — it’s probably not a fair way to get a sense of the place. The hardwood shut like an airlock. Lunch service was not busy. Assuming the list online is up to date you can still drink very well here if you’d like, and affordably too. A bottle of 2008 muscadet from Jo Landron, maybe? 2014 sémillon from now-defunct Dirty & Rowdy (!?).

Daniel Vollenweider died in 2022, in the summer. I never met him personally, although his wines were among the first I felt like I had a relationship to as a baby somm.

I didn’t really clock it at the time, but they were arriving in the market at the same time that I was. This harvest, 2014, was the year that Daniel started working with Stephen Bitterolf, just after he’d started his company. Vollenweider was the fifth grower Vom Boden represented. You can read Stephen’s reminiscence of his friend here.

We’d fight our way free of the Loop, eventually, and find our way to the parts of the city where real people live. In the meantime, however improbably, here was a sliver of something undeniable: glowing and green and impossible to render down.

PLĒB ‘Noble Carlos’ muscadine co-ferment Appalachia 2021

Another birthday — not mine, this time — and another bottle of Pleb. It was a sample shiner with a year of age on it and I’d thought it’d be a fun thing to open at a celebration in the ripe, falling-apart height of summer: a co-ferment of two varieties of muscadine, one bronze and one purple, exuberantly perfumed on the nose and bone dry on the palate, the classic head fake of an aromatic grape variety in the hands of a natural winemaker.

Muscadine is the most outlandish of the all of the non-vinifera natives and multi-vitis varieties getting made into wine out there — the most genetically distant, part of an entirely different subgenus than the rest of the vitis species, with 40 chromosomes instead of 38 and fruit somewhere between a gordo olive and a bronze golf ball.

It pulls a weird trick with its aromatics: they feel totally unexpected (wine isn’t supposed to smell like this!) and also deeply familiar (this couldn’t be anything other than what it is; you belong here; this is home).

Pleb’s bottlings were the first time I’d ever tasted a native fermentation muscadine wine without sweetness. I think that’s probably true for a lot of people.

Rather than feeling like a weird loner—some kind of unique singular genius—it instead suggested a whole parallel dimension, full of superheroes in alternate costumes, recolored national monuments, as-yet unmet versions of our main characters wearing goatees or eyepatches. There could be dozens of wines like this, you’d think. Hundreds. Someday, you’d be able to organize tastings across the stylistic and regional spectrum, like it was muscat: your dry Alsatian hock bottle, your skin-contact wild child from an island in the Aegean Sea, an ancestrale version from northern Italy…

Bottles like this taste like celebration, because they taste like abundance. Here’s something that grows everywhere, like a weed. Look what it can do.

CABANON ‘Poudre d’Escampette’ carignan, mourvèdre, grenache noir et gris Roussillon 2022

Here’s another way a wine can be: deep, grounding, like a thick bassline or tomato paste at the back of a long-simmered stew — and also one of those things special enough that it was kept for us so that we could have the last glass or so after walking in from service.

A big table full of friends in south Brooklyn, at the heel end of the night because we’d all been working that evening. (One of the stretches in the back half of the year where I spent a week or two helping a friend out with service, snapped back to a more centered, conscious version of the work I used to do all of the time: could this thing make an honest man out of me?)

This is from a little plot of very old vines, just inland of the ancient thumb-sized Mediterranean port of Banyuls, in the mountain borderlands along the Catalan coast that you would have walked across if you were fleeing the fascists after they took Barcelona—and just a few years later, where you might have crossed in the other direction, getting ahead of the French capitulation to a different set of fascists.

We’re a half hour by train from the Catalan coastal village where, in September 1940, the brilliant German-Jewish writer Walter Benjamin, on hearing that the Spanish police would be acceding to France’s request to return his group back across the border, killed himself overnight in his hotel room by swallowing morphine tablets. Hannah Arendt crossed via the same route three months later.

Alain Castex, an old-school French communist, would probably have appreciated the context. In 2015, he finished out a decade and a half as the natural winemaking legend behind Casot de Mailloles, an estate of scattered plots on schist a little closer to the steep rocky insanity of the coast, which he passed along to a handpicked successor.

The little flat inland old vines of Vins du Cabanon, commercially ludicrous, farmed with he called ‘subsistence viticulture’, was what he did afterwards instead of retiring, alongside mentoring a blossoming new generation of Roussillon natural winegrowers.

Alain is gone, too. Last June, in his vines.

“Happily,” he said in a 2019 interview, “there are new people who arrive, to launch the adventure. There are a lot of young people.”

MARK ANGELI ‘V.V. de Blandières’ chenin Anjou 2021

A bottle that arrives just as it is. Not as an adventure or a challenge or a brainteaser, but in the satisfying way that, like, Casablanca is satisfying as a movie: classic, often-referenced, extremely influential, sure, but also damn if all of those little bits of business in the café and one-liners you’ve seen parodied in decades of subsequent media still don’t hit. No matter how many ways it’s part of the canon now, there’s still a freshness and vitality there, a feeling of the unexpected, or unexpectedly sharp.

Mark is a guy as consequential to the young people adding their energies to the scene in Anjou as Alain was in the Roussillon: he’ll be the one lending you his tractor, or pointing out a little plot of vines that a old-timer was putting on the market so that he could retire.

We shared it with my little sister, who was in town solo for a couple of days. (She is perpetually ‘little’ to distinguish her from my other younger sister, even though she parents two children and is more financially stable than I’ve ever been in my life.) She loves food, worked in a professional kitchen when she was younger, and doesn’t get to go out a lot. (See “parents two children”.)

Naturally, it was our mission and our pleasure to style her out. We took her to the Four Horsemen; everything was extremely nice, she loved the black-and-white ouefs mayonnaise with the squid ink and caviar, etc, and when this bottle landed it was—what’s the technical term?—perfect.

I drink a lot of chenin, but when was the last time I sat down with a bottle of Mark Angeli at a meal? (Not any other time this year and not in 2023, say my records.) And also: have you ever, like, shown Casablanca to someone who really enjoys movies and was a PA on set once in college and likes talking about film but has never seen Casablanca before?

PLĒB ‘Foundy Rosé’ jacquez et al Appalachia MV

Pleb was always going to be on this list, for the reasons that hopefully have become clear. Then, at the end of September, Helene came to Appalachia.

As Kara Daly* of the western North Carolina–based project ‘Wine Is Confusing’ wrote shortly afterwards:

“Warming temps are bad for winegrapes, but the other climate threat to the wine industry is that an unprecedented storm could flood your beloved, mountainous region, shredding access roads to historical towns, and snatching water infrastructure, cell towers, and power lines. It could pull neighborhoods down their slopes like a shade over a window. As easy as water can bend an iron beam, the supporting structure of your tourism-reliant industry could simply drift away.”

And so it went in the River Arts District in Asheville, Pleb’s fermenters filled to the brim with the new harvest, every tank and clay onggi and barrel and concrete egg carrying the wines that would become part of multi-vintage soleras and age on their lees for a half-decade before bottling and be blended into the base for sparkling wine programs.

Chris’ cellar practices had a lot to do with finding resilience in a marginal climate, a place where yields could swing dramatically from vintage to vintage and acidities could need tempering and it’s a question of finding richness in a place where richness isn’t necessarily coming from the sun. (You know, like in Champagne.) But there’s a limit to the resilience your aging program can find when the winery itself gets reduced to its foundations.

I poured this rosé, a glowy thing from a solera bottling meant to be the winery’s calling card, at a sip n’ paint hosted at Bin Bin Sake in Greenpoint to raise funds after the full weight of what had happened to Asheville and the rest of the region had landed.

I drank my own glass while redrawing, in pen on watercolor paper, the fiddly fractal coastline of the mid-Atlantic — Delaware is a real pain — and the 400 year-old Mother Vine on Roanoke Island, a muscadine that is the oldest cultivated grape vine in North America — and the valleys around Asheville that had funneled the floodwaters.

These bottles were rarities, now. Not things to check in on and follow as part of a journey (can’t wait to see how it tastes next vintage!) but fragments of ruins that would take years to rebuild. Reminders, too, of why rebuilding was worthwhile.

* Due to an editing error, Kara’s first name was misspelled as “Karen” in the newsletter I wrote about Pleb in the wake as Helene. We are mortified by the error. Follow her work!

BRUYÈRE-HOUILLON ‘Nouvelles-Viaduc’ savagnin, chardonnay Arbois 2015

Credit Jirka up there on the right for the phrase “princess moon juice”, now one of my most-craved white wine categories.

The illumination is candlelight, not electricity. The texture is satin, not wool. If there’s any lightning, it’s trapped in a Tesla sphere, and reacts to your touch.

Picture yourself sinking into a pool lit only by stars, or as Stellan Skarsgård emerging from a mud bath.

Back in 2015, I had business cards that said “sommelier” on them for the first time. In terms of “look,” I’d say it was my cartoon pilot era.

These days, as I and my cohort age out of being young and hungry and into the Baron Harkonnen phase of our careers — mud baths, feasts at the head of banquet tables set before defeated opponents, responsibility over entire planets — a bottle like this is one of the consolations for having stuck around long enough to find out. Mirror universe white burgundy with a little more mustard on the eight ball thanks to the savagnin, rare as hen’s teeth, given some time.

I don’t know whether our younger selves would think we’ve made it — I don’t feel that way — but they’d have to be impressed with how well we’re drinking.

MARIAM IOSEBIDZE ‘Vinônô’ tavkveri Kartli 2020 in magnum

Something so nourishing about this. Bright and low-impact and refreshing, sure, but rooted, too, glowing red things from the earth, beets and rhubarb and roses. The feeling of pushing your feet underneath the sand at the beach.

We opened this as part of a kind of rolling snowball of a holiday party that ended up at a new wine bar at the bottom of Manhattan: a big bottle for a big group.

Magnums are a great place to score a wine with a little age — it’s harder to find an excuse to crack into them, and they tend to hang out on lists longer than regular-sized bottles do. It’s also a way to ensure that you get to spend more time with a wine than a single taste if you’re drinking with five or six other people.

Mariam worked at Gvino Underground in Tiblisi and did natural wine tours for Living Roots. In 2014 she made her first vintage of tavkveri at her uncle’s marani in Kartli, outside of the city. Pretty emblematic of a lot of the young Georgian new wave taking the baton from those stubborn old guys in the village who’d been the last guardians of winemaking that didn’t come from a factory.

She macerates for a few days before taking the skins out of the qvevri and leaving the juice in clay to finish fermentation and settle clear over the winter, a lighter touch than you might have been picturing for Georgian wine, from a grape that does deep stained-glass rosé really well.

By all accounts the wine can be a little knees and elbows right after bottling. A few years on, it’s a somatic reset.

OLIVIER HORIOT ‘En Valingrain’ rosé de Riceys Aube 2008

In a year full of wines the color of rose gold and ripe peaches and Miami sunsets — the ideal wine color, for chaos and instability, for seasons bent out of recognition by climate change, for momentary brushes with the good life (you may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like) — I had to be stern in pruning.

We’ve already seen skin-contact catawba, and solera jacquez, and tavkveri in qvevri. (You know, the “big three”.)

Among many alternates and almosts that might have found their way onto this list, on a different day:

Palestinian-American Laila Maghathe’s pulsing, neon “Love Letter”, a co ferment of marini and merwah, made in the mountains of northern Lebanon and carried in my backpack on many a day out on the streets; Sepp Muster’s “Vom Opok” rosé, “air conditioner wine” at Lise & Vito’s [ABV] Ferments afterparty; Borachio’s heartthrob co-ferment down in Adelaide necked with a colleague in a back yard while I talked about how the election had surprised me and she talked about how it hadn’t; a different qvevri rosé from Gogita Makaridze at my twentieth high school reunion; a quarter glass of 2017 l’Anglore with a bite of foie toast and blackberry jam at a beautiful wine-soaked wedding on a farm in Kentucky…

But we’re here, at a pre-Thanksgiving dinner at Chambers with my mom and Olivier Horiot’s 2008 rosé de Riceys, which Pascaline fished out of the cellar as a treat.

I remember meeting Olivier late-night at Racines at a small tasting Pasca organized five or six years ago; he ended up talking with us until late into the night.

He talked about rosé de Riceys as the only appellation in France that required a proportion of carbonic maceration. He talked about layering whole-cluster and destemmed grapes like mille-feuille. He talked about making his champagnes like they were still wine, and his still wines like they were champagne. He talked about the silliness of making two different single plots of rosé de Riceys, and how different they were from one another. He talked about he and his wife taking shifts during the slow overnight press and tasting the wine every hour, until they felt a whisper of tannin.

These grapes would have been harvested sometime between mid-September and early October. Maybe I was looking for apartments in Jaén while they were getting picked, or trying to figure out how to say “contact lens solution” at the pharmacy in my neighborhood.

Now here they are: altered by fermentation and oxygen and slow, complicated, subtle chemical processes, uncorked and poured into a glass to make you feel a way, one time only, that you can try to remember and commemorate.

Time is the one special effect you can’t fake.

Not so long, now, until we start another year.

I don’t know what’s coming, but I’m glad to be here with you.

See you in 2025,

grape kid

One thought on “Ten wines for 2024”