Welcome to the wine info page for CLUB shipment #1: the RHÔNE river — now open to the public!

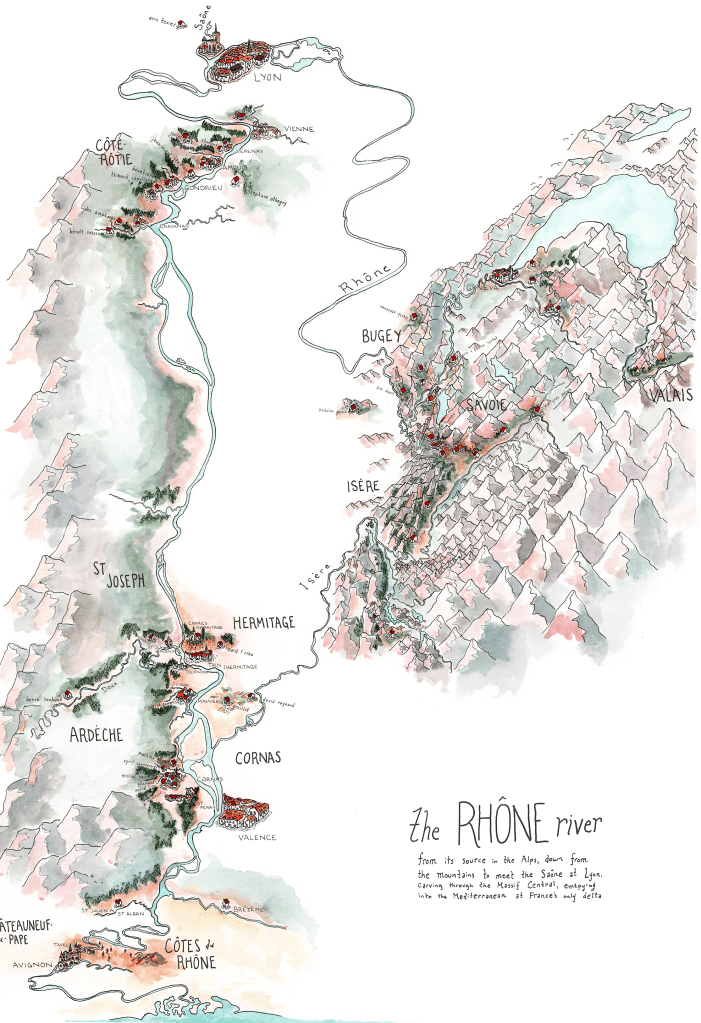

the RHÔNE river

The Rhône is most famous for wind-buffeted, single-stake syrah clinging to the steep slopes of a valley carved through a granite plateau — or for magisterial, sun-soaked red blends from the soupstone-strewn vines surrounding a former papal palace.

But rivers invite continuity. They flow, they rush, they let us go tubing from one place to another. The Rhône doesn’t begin with Côte-Rôtie or end with Châteauneuf. It’s born in Alpine glaciers, and it ends in a delta that mingles with the Mediterranean.

What could we learn by following it from start to finish?

Hi everybody,

I had a lot of fun putting together this lineup for you! Below, you’ll find a little more information about the people that grow them, the landscapes they’re rooted in, and what you might want to do with the bottles you open.

Before we get into specifics, here are a few touchstones to keep in mind:

These wines are grown and made on a human scale — made by people, not organizations, and, particularly, by people worth getting to know and who I’m excited to support. (There is too much good wine out there to reward shitty human beings!)

I’ve focused on folks whose first vintage was within the last ten years. Maybe their first harvest was just before the pandemic — or the wines have only been in the US for a couple years! Between scale (small) and timeline (new) they’ll be bottles that are hard to find out in the wild, from producers who are probably new to you (even if you drink a lot of wine), and my hope is that they’re a taste of the future of their regions.

They’re farmed without chemicals, fermented with native yeast, and bottled without addition or subtraction, apart from maybe a touch of sulfur at bottling.

(Just a quick note here: farming without chemicals is a big deal both because of its impact on soils and watersheds but also because of how rare it remains. The French national average for organic certification in vineyards is only around 20%. That said, I’ve been heartened by a substantial increase in conversion to organics over the last decade. When I started in wine, the French average was closer to ten.)

All of this means that these bottles are ‘natural wines’, in the big-tent sense of the word. They’re not necessarily going to be funky—some of them will stretch out to wilder and weirder edges of the spectrum of possibility, and some of them will taste clean and classic—but all of them will be alive. They’ll move and change with air and time, and unfold and show different sides of themselves as you get to know them.

As I mentioned in my note, that means that you’ll want to put them somewhere cool and dark after they land — ideally, below 60°F. (The back of your kitchen fridge is fine! Too cold > too warm.) It means they’ll want to settle down for a little while before you open them, to recover from their journey. (Call it a week or so minimum to be safe.)

Finally, it means that if you’re not a huge fan of how one of these tastes right when you open it, it’s worth letting it hang out to see where it goes!

In particular, air will be a big help. You can use a decanter if you have one, but a flower vase, French press, etc all work. Just make sure the vessel is clean and doesn’t smell like anything (dead flowers, coffee grounds, soap suds). If it does, rinse with a little hot water. Bonus Michelin-starred service tip: rinse your decanter with a little of the wine you’re about to dump in.

I’ll have some pairing suggestions for all of the wines below, but remember that there are plenty of ‘right’ answers to the questions, “what situation do I open this bottle in? are we having food with it? what kind?”

Give yourself a little grace, don’t sweat it if you don’t have the time or ingredients to follow a suggestion, and remember the most important thing is being present, paying attention, and having fun.

Ok! I think that’s about it for the preliminaries. (I could do this for pages, unfortunately.)

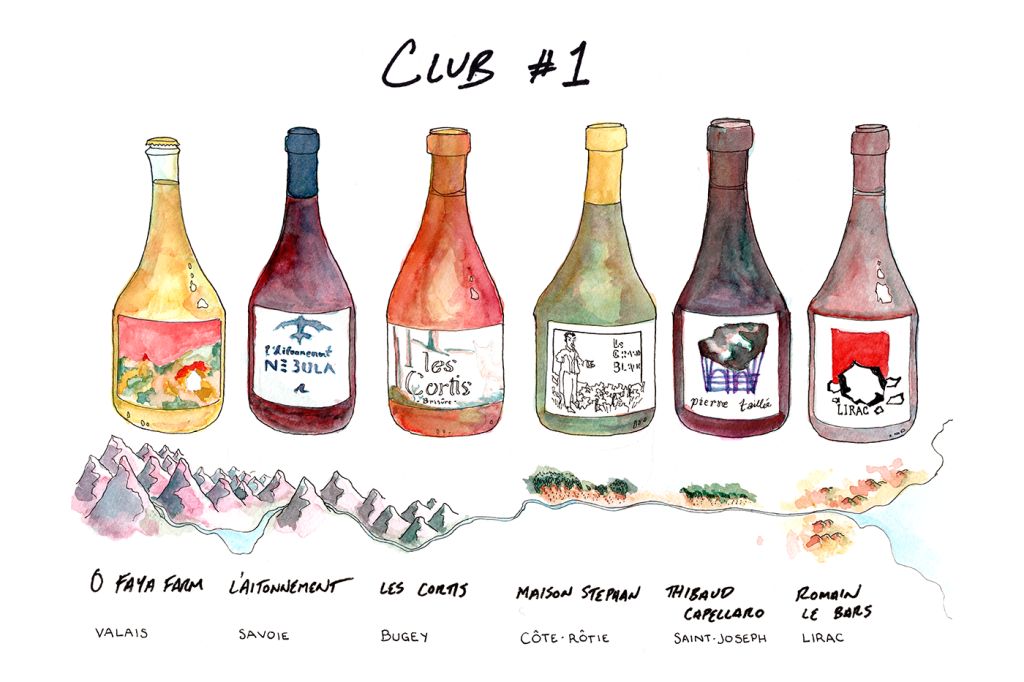

Let’s chat about the wines. We’ll go in river order, starting in the Alps. If you have the abridged 3-bottle pack, you’ll be coming in at every other one.

Skip ahead to longform notes:

Ô Faya Farm

l’Aitonnement

Les Cortis

Maison Stéphan

Thibaud Capellaro

Romain les Bars

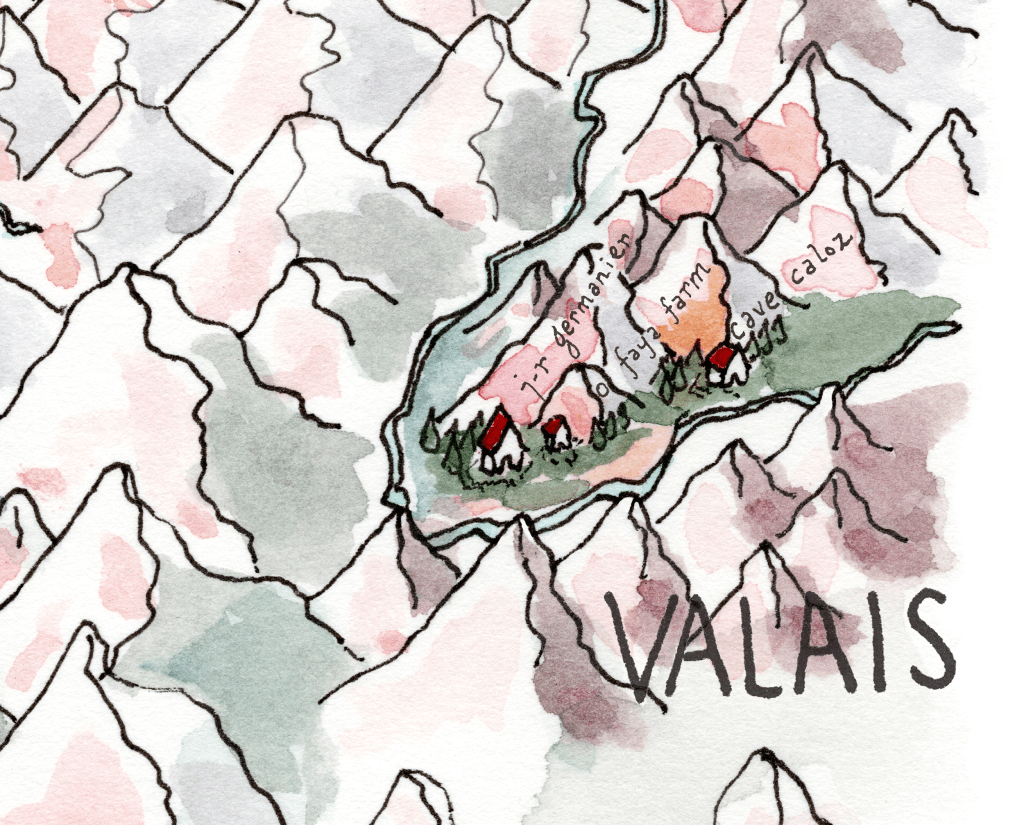

Ô FAYA FARM

Who? Ilona Thétaz, who started her own wine farm (plus apricots and sheep!) in 2020. The place is the Valais, the glacial Alpine valley carved by the Rhône before it spills into Lake Geneva. The grape is heïda, better known as the Jura’s savagnin. What to do cook a thoughtful dinner Bodega pairing international snack attack a la unsnackable, my pandemic comfort read; I’m dreaming of Lay’s Green Onion (apparently only a thing now in central Europe?) or Korean shrimp chips from H-Mart

More? Ok, more!

L’AITONNEMENT

Who? Maxime Dancoine, who arrived in Aiton in 2016 to collaborate with the village’s last remaining winegrowers. The grapes are douce noire, once the most-planted red variety of the Savoie, now nearly extinct in its birthplace—as well as a bit of mondeuse, syrah’s mountain cousin. The place is the Savoie, specifically the glacial Alpine valley carved by the Isère. What to do impress a wine snob Bodega pairing chopped cheese sandwich (for non NYers)

More? Ok more!

LES CORTIS

Who? Jérémy and Isabelle Decoster Coffier, who bought their first vines from a retiring grower in a handshake deal in 2016. The grapes are red and white together: red-fleshed gamay teinturier, and golden altesse. The place is Bugey, a crumpled section of the foothills of the Jura mountains in a loop delimited by the Rhône river. What to do celebrate the spring Bodega pairing Seaweed chips

More? Ok more!

MAISON STÉPHAN

Who? Romain and his natural winemaking legend / father Jean-Michel Stéphan. (Romain joined in 2017, and together they planted new vines they farm together). The grapes are the white varieties of (this stretch of) the Rhône: marsanne, roussanne, and viognier. The place is the ‘northern’ Rhône (really its middle), specifically on the plateau above Côte-Rôtie and on the slope outside of the famous village of Condrieu. What to do call either a living (not emotionally abusive) family member or a friend you haven’t talked to in a while, tell them you love them Bodega pairing Fried egg + scallion cream cheese on a sesame bagel

More? Ok more!

THIBAUD CAPELLARO

Who? Thibaud Capellaro, a first-generation winegrower who started assembling his small collection of plots around the blue chip real estate of Côte-Rôtie and Condrieu in 2018, after working across France and in Australia. The grape is syrah, emblematic and savory red variety of the stretch of the Rhône between Vienne and Valence. The place is the ‘northern’ Rhône (really its middle), specifically two historically undistinguished plots, one in a village south of Condrieu that qualifies as ‘Saint-Joseph’, the other across the river. What to do fire up the grill Bodega pairing fancy paleo-compliant spiced jerky

More? Ok more!

ROMAIN LE BARS

Who? Romain le Bars, an acolyte of beekeeper and iconic natural winegrower Eric Pfifferling (l’Anglore, the wines with the salamander on the labels that are rare as hen’s teeth). He made his first vintage at Eric’s place in 2018 after working for him for 7 years. The grapes are equal parts the very Mediterranean / Provençal varieties grenache, mourvèdre, and carignan. The place is Lirac, a village on the west side of the Rhône river just before it spreads into its delta, next door to the more famous dark pink wine village of Tavel. What to do crack open on Valentine’s Day, watch the season 3 premiere of Yellowjackets. Bodega pairing that plus a 5mg weed gummy

More? Ok more!

Ô FAYA FARM

More? Ok more! Ilona has been working in wine since an apprenticeship in 2013, although she originally wanted to be an actress and acrobat. She made her first wines for herself basically at home, for friends, in 2019. Her farm started in the village of Saxon in 2020, but after a devastating 2021 vintage (the year she also fell in love) she relocated to Conthey, a steep, rocky, wild place overlooking the Rhône in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, just upriver. The sheep and apricots are still with her.

Switzerland makes a lot of wine, and drinks almost all of it. The bottles we see in the export market tend to be old-school, expensive, and a little staid, although well-farmed. Lots of capital-Q Quality. The Alps, for all that they’re a natural barrier and an archipelago of local dialects and isolated valleys, are also a crossroads. The grape varieties reflect this, mixing southern Germany (chasselas, sylvaner) with eastern France (gamay, pinot noir, savagnin, chardonnay) — along with local mutations, obscure specialties, and variations all their own (cornalin, petit arvine, humagne…)

Ilona was able to get financial support for her project through a Swiss crowdfunding app called Yes We Farm; her looser, light-touch approach in the bottle and devotion to polyculture (her apricots, sheep, cows, and two donkeys), not just viticulture, is a good snapshot of the current young energy in the country’s wine scene.

Savagnin is a late-ripening, high-acid, thick-skinned variety — an ancient, possibly wild cross between even more ancient progenitors, propagated for a very long time and so, like pinot, having accumulated a laundry list of mutations, local specializations, and epigenetic quirks. Here it’s a slow press into neutral 225L barrels, where it ferments and sleeps through the winter before bottling in late spring with no additions apart from a dab of SO2 at bottling.

Spice — cumin, cardamom — would be fun to play with here. Coat a cauliflower head in gochujang and roast it. Steam cod with ginger and spring onions.

All else fails, this is great cheese plate wine, especially comte or firm sheep’s milk manchego with age.

L’AITONNEMENT

More? Ok more! Maxime was trained in Switzerland — the river makes connections — and arrived in the Savoie only in 2010. He worked for pioneering organic vigneron Louis Magnin, and then for a local oenologist laboratory which covered most of the region, one of those behind-the-scenes jobs that puts you in touch with a lot of different people and gives you a lot of deep experience, very quickly, of place.

He ended up landing in Aiton, tucked up the Isère river in what is today a pretty neglected part of the Savoie (see also: Ardoisières, very nearby in St. Pierre de Soucy, which is also where Maxime aged his first vintage). It’s a lot of steep slopes abandoned because they can’t be worked by machine, old nearly extinct cultivars hiding in backyards, faded legacy of wines that, as of the 19th century, were written about as able to “rival the Graves and the Chablis.” Phylloxera, modernity, two world wars, and by the 1950s the vineyard area is a tenth of what it once was: a familiar, sad song.

He took over from the last two vignerons in the village: 58 ares, half the size of Gramercy Park, and has recuperated about a hectare and a half more, plus a new field planting of massale cuttings of a bunch of different cultivars (some of which I’ve never seen before, and this is a special interest of mine!): verdesse, molette, blanc de maurienne, petit saint marie, gringet, and the white and gris mutations of mondeuse. The plots are fragmented and small and in some cases the only way to get to them is by hiking little footpaths like a mountain goat. Maxime believes, as I do, that polyculture and genetic diversity in the vineyard can be a source of resilience against climate change.

The vibe of the wines is, I don’t know another way of saying this, ambitious. There’s a high gloss to them, an evident care and elevated threadcount that makes them very at home on white tablecloths when I’ve served them in fancy wine hospitality situations. He orchestrates ceramic vessels, clay amphora, concrete, 400L demi-muids for his aging, has an entire paragraph on his website about the company he gets his bottles from and how he cleans them, etc. It seems to me he’s looser and more uninhibited in the vines, and a bit more technical and fussy in the cellar: a familiar type.

The grape on stage here, douce noire, is one of those nearly forgotten local cultivars (in 2007, France’s official grape census counted 2 hectares of vines—a hundred thirty years ago, it was the most-planted grape in the Savoie), but it’s had an unexpectedly well-traveled second life.

Recent DNA analyses revealed that it made its way to Argentina, where it’s the second most-planted wine grape in the country, called bonarda, (apparently unrelated to a northern Italian grape of the same name), and that it was also brought to California by Italian immigrants, where it’s called charbono (from charbonneau, a synonym in the Jura). As turca, it’s been planted in the Veneto for a hundred years. The Alps are a barrier and a crossroads.

For a long time it was thought that douce noire was maybe a dolcetto relative, and it’s easy to see why—it has a similar plummy sappiness. When I first tasted it as charbono I filed it in my head as one of those grapes that tastes like its name: a kind of grilled, roasty-toasty steaks over open flame energy. If you’re having dinner, consider preparations with a little char, the caramelization of dates in savory recipes, lamb tagine, black olives. Not only might I pair it with the same things I’d pair with syrah or with a northern Italian red, it could be fun to pop say, a dolcetto from San Fereolo or Cascina Corte in Dogliani, or your bottle of syrah from Thibaud Capellaro, or a teroldego from Elisabetta Foradori, taste them side by side, and see what resonances you find.

LES CORTIS

More? Ok more! Jérémy and Isabelle come from music, but I can’t tell exactly what the vibe is and I haven’t heard them play. One of their importers says “indie band”, one says “classically trained”, and one says “Lounge Lizards.” I am not sure how to square that circle! (Sidebar: it’s always funny to see how a grower’s work is represented by the people who sell them outside my market — on the west coast, or in Australia, or Japan, or the UK — when I’m trying to look up facts about them on the internet. Narratives shift, references and voice shade towards the local audience, information is different levels of up-to or out of date, and what, really, is truth? Jk I used to be a fact-checker, I have some thoughts about what is verifiable and how to do so.)

Anyway, as in many fields who you apprentice with matters: they worked for years in the vines and the cellar with Alice and Olivier de Moor, natural winegrowing legends of the Yonne. (The Yonne means Chablis, sure, but also so much more.)

They moved to Bugey in 2016 — a handshake deal with a retiring farmer, as you read up there. Bugey is a few different things.

Politically it was a fief of the House of Savoy for almost 600 years, before European nation-states began to coalesce like planets. It was ceded to France in the 1601 treaty of Lyon, which concluded a yearlong war between the King of France and the Savoyards over a little French enclave in the Piedmont called Saluzzo. (Motto of the marquisate: Non sol per questo, ‘Not only because of this’.)

Geographically it’s defined by a loop of the Rhône river around the crumpled-up southernmost foothills of the Jura mountains: little island clusters of vines separated by forested limestone plateaus mostly trying to face south and soak up the sun. And those clusters are tiny — Bugey as a whole only has 500 scattered hectares under vine, a drop in the bucket compared to Saint-Joseph (~1200), Croze-Hermitage (~1800), or oh my god the southern Rhône (50,000++?!!). There are structural reasons you’ll find Côtes du Rhône in Costco and not Bugey, you know what I mean?

As for the wines themselves, it’s a place where you feel the transition between that Alpine energy and Lyon, due west, with Beaujolais orbiting that city like a purple granite moon. There’s Savoyard altesse and mondeuse, but also Burgundians like gamay and chardonnay and pinot noir. Bugey makes, proportionally, a lot of sparkling wine. Up north, where it shades into the Jura, there’s even poulsard, most notably (for those of you studying for exams) in the frothy sweet pink fizz of Cerdon.

Anyway, anyway: Jéremy’s work is also noteworthy because of his farming: no-till / regenerative, with an emphasis in his new massale plantings on intentionally arranging field blends that he ferments together, so that most of the new cuvées are site-specific co-ferments.

With “Brisure” you’ve got a paradoxical 50-50 blend of princess-peachy altesse (name literally means “your highness”) and a red-fleshed (teinturier) local variant of gamay, a genetic mutation that has cropped up independently a few times and has different local names, useful for adding color, carries a certain degree of stigma.

Both grapes are direct-pressed, so after blending the bright pink of the teinturier gamay juice with the pale flax of the altesse you get a golden-pink rosé that, for arcane legal reasons, says it’s red wine on the back label. (For one thing, it’s not allowed in most wine regions in Europe to make a rosé by blending red and white together.)

Blends or co-ferments of different-colored grapes are what the vast majority of ancestral wines were, historically, everywhere from pre-Prohibition California to pre-1890s Chianti to Champagne in the 1600s (I’m just thinking of places I could find citations for in the next 30 seconds if you asked me). In Moravia these wines, made from what they would have called blue and green grapes fermented together, were called rysák, ginger; in Spain, tinto + blanco was clarete; in Franken, rot + weiss made rotling.

Apparently the fashion right now in France, where multicolored co-ferments have become increasingly part of the natural winemaking toolkit, is to call them blouge (blanc-rouge), which I think sounds extremely silly and a little bit obnoxious. (Cue joke about the French.) Anyway, like a lot of nouveau-futuriste vin nature stuff it’s brand-new, no word for it, seemingly suddenly being practiced all over the place — and also deeply embedded in wine’s deep ancestral past, especially the bits of it overwritten by modernity.

This particular co-ferment, rather than being plush and white-peach-gummy in the mode of most of Jérémy’s white wines, is edgier and silvery. Too cold and it might be just a laser pointer. Air and a little bit of warmth fills it out.

Crunchy, bright, maybe a with a little fat in the bassline — this is the general energy to aim for, as far as my pairing recs. I opened this while making stir-fried celery with peanuts, spicy sausage and chili oil out of a Carla Lalli Music cookbook along with some roasted sweet potatoes dressed with tahini butter and lime. Perfect pairing? No — but very satisfying.

I think this would also be amazing shrimp cocktail wine.

MAISON STÉPHAN

More? Ok more! Jean-Michel Stéphan is one of the quiet natural wine icons of the northern Rhône, a guy that I first got to taste in earnest when I worked for Pascaline at Rouge Tomate: minuscule production, iykyk wines, in the vein of Cornas diehards like Thierry Allemand or Marcel Juge.

The big difference was that he wasn’t down there in Cornas, tiny village of blood and iron, with all of the other real ones still left standing. He was up in Côte-Rôtie, the roasted slope, the glossiest ’90s Michael Bay movie flagship of the northern Rhône’s revival from obscurity and near-extinction, the place where Robert Parker, beading sweat like a boiled ham, rubbed his hands together and said now THIS IS WHAT I CALL WINE.

Côte-Rôtie, like Hermitage, is the expensive, classy side of syrah in the (what we call) Northern (but is actually more like the middle) Rhône. The roasty slopes are clustered above the town of Ampuis, where superpower négoce (and architect of the Michael Bay movie-fication) Guigal carves out their headquarters, producer of everything from the cult ‘LaLa’ single-parcel Côte-Rôties, robed in their toasted new barrique, to their 4.5 million annual bottles of sub-$20 Côtes-de-Rhône rouge sourced from fruit a hundred miles south.

Jean-Michel planted his own vines in 1986, on steep, rocky land that his grandfather, who farmed apricots and trellised grapes at the ends of his vegetable rows to make a few barrels for the local bistro, had gotten thrown in almost for free along with some flat, fertile farmland on the other side of the river, then the more desirable buy.

His first vintage bearing fruit was 1991. For the first few years, he sold to (guess who) Guigal, before making his first independent vintage in ’94. He always farmed organically, despite that being a vanishingly rare approach (including on his family farm), and very quickly he was in the same rooms as the embryonic French natural wine movement, which back then could fit into Marcel Lapierre’s living room.

Most of the time when there’s an old-head natural winegrower who becomes a quiet icon after two decades of work, the wines only get harder and harder to find.

Jean-Michel, though, is one of the rare quiet natural wine icons who as an old head has been slightly increasing production. His son, Romain, joined him in 2017, and Romain’s brother followed shortly thereafter. Together they planted 5 more hectares of vines scattered between five different hamlets on the fringes of the now-fancy roasted slope.

The white you’re drinking is from four of those plots, and from the three more rarely-seen white grapes of this stretch of the Rhône, so often thought of as purely syrah country: perfumed disco queen viognier, and the Rosencrantz + Guildenstern pair of marsanne and rousanne, who I always think of as playing this game.

While drinking a bottle of this with my partner, we pinged back and forth on what fruit, exactly, we were tasting. Banana, I said, maybe banana runts? White cherry, she said. Lychee? I said. Golden apple, she replied.

We caught ourselves after five minutes of this. Fruit salad is kind of a trap. You can list them for hours, but it’s really always more about color and shape and energy: a mouthfilling, oily weight; the feeling of sun; and the big synesthetic color wheel of this wine, a kind of buttercream yellow-pink swirl. I don’t know what the marketing boys named the flavors the science folks put in the swirl, but I know how the swirl feels.

Food pairing? Anything you’d put drawn butter on and be happy you did too: golden fried rice, lump crab pasta, a stack of pancakes, a perfect omelette. Treat it like bearnaise sauce.

Another secret superpower of rich, dense white wines like this is that they’re really, really good with fancy dry-aged steak. This and a ribeye fat cap?!

THIBAUD CAPELLARO

More? Ok more! Thibaud is a local kid, but not someone from a winegrowing family. He’s cobbled together his small domain from abandoned plots, mostly inside and around Côte-Rôtie, that were historically not considered ideal: steep, not facing full south — now, in hotter times, not something you have to worry about.

He’s spent the last half decade rebuilding terraces, planting new vines, and doing all kinds of unconventional things in the winery: aging vessels ranging from oak and steel to terra cotta and fiberglass, inverted 90-10 white-red blends, and would you believe there’s little to no sulfur? He buys a bit of fruit in addition to what he farms, as far afield as Lyon and the Ardèche, and has a collaborative winemaking project with a group of friends called Juicy Squad. All very DIY punk-rock, all very contemporary French natural wine scene, all very unlike that classic Côte-Rôtie vibe.

“Pierre Taillée” comes from two of his own plots, both close to his new winery just south of Condrieu. I’ve done a couple of things here: This is me grabbing something from Thibaud’s own farming rather than the grapes he buys, which struck me as a special treat. It’s also 100% syrah, and a good moment in the lineup to give syrah its flowers.

Who is syrah, anyway?

Born to parents dureza and mondeuse blanche, it’s a child of the Alps just like its mother river is. It has relatives spilling over both sides. Uncles like mondeuse in the Savoie and teroldego in the Dolomites, second cousins like lagrein in Alto Adige. And it carries itself unmistakably: lavender and olive, smoke and char, pepper and bacon fat. (Insert your own preferred dark and savory things.) As a baby wine professional, I would have said at one point it was my ‘favorite grape’.

I think when you’re looking for words to describe wine, trying to distinguish between one thing and another, there’s a real appeal in something so clear, so unapologetic, so obviously about something more than just fruit.

It’s been a long time since syrah belonged only to this little corner of the world — but if you’re going to go rivertubing down the Rhône, there’s also no escaping saying hi when you come home.

I haven’t opened this bottle since I tasted through a lineup of all of Thibaud’s wines last fall to decide what to include in the shipment, but I remember what struck me: an instant feeling of this is syrah; the sort of dimensional, loose, can’t-pin-this-butterfly-to-the-wall sense of movement and life that is what I love about natural wine; a grounded depth that made it stick out.

Did somebody want tech info? Oh, ok: whole cluster, light extraction, big ol demi muids, 15ppm sulfur addition.

Lucky enough to have a backyard or a rooftop? Worth doing some open-flame cooking. Don’t let it get too warm. Put it in a decanter if it misbehaves.

ROMAIN LE BARS

More? Ok more! I drank at least four bottles of Romain’s rosés for pure pleasure last year — off the shelf at Plus de Vin in my neighborhood, in the basement at Cellar 36, out to dinner at Four Horsemen with my little sister, at home while doing what we’ll call “R&D” for this club — to say nothing of tasting through the lineup in more professional settings.

In the same way that you can tell what the “best” wine was at a wine-person gathering not based on what people say while they’re tasting, but on which bottle empties first, there’s something to be said for Romain being one of the producers I voluntarily went back to the well for again and again last year. In a lot of different circumstances, in a lot of different places, I saw him on a list and thought, “mm, that sounds good.”

We’re in Tavel, a tiny village facing down Avignon and Châteauneuf du Pape from the opposite side of the Rhône, just before it splays out into the Mediterranean. Hot, dry, growing a palette of grape varieties that leave the Alps almost fully behind; instead of the river connecting us to distant mountains, we’re seaside, on an arc of western Mediterranean regions from Catalunya to Genoa, linked by ancient sailing routes and trading ports. Grenache country; cinsault and carignan and mourvèdre singing backup. Your points of comparison down here are more likely to be Provence, or Banyuls, or Liguria, or Sardinia.

Tavel is tiny, at less than a thousand hectares, and occupies a place of niche fame, mostly among red-cheeked British wine writers, for its distinctive darkly-colored, ripe, tannic rosés. It gets a lot of column inches in standard texts and exam prep materials because it’s a classic “exception” appellation—the AOC requires pink wines and has since the 1930s—but a lot of the actual wine is deeply mediocre and a little expensive.

It’s against this backdrop that we find Romain and his mentor, the former beekeeper and emblammatic natural winemaker Eric Pfifferling, who makes a rainbow of cult wines under the name l’Anglore, wines that have never actually been particularly expensive but have been almost impossible to find since the early 2010s, which is when I first encountered them as a baby sommelier whose boss was constantly posting them on Instagram with zero context. (What are these salamander wines, I thought to myself. Must be special, I guess.)

Anyway, working with Pascaline at Rouge afterwards I got to taste my bodyweight in l’Anglore with appropriate age and so have earned the following take, as insufferable as it is: the real secret to enjoying a bottle of l’Anglore is to drink them with a little bit of time — four or five years under cork and they get really special and distinct, but on release they all kind of taste like yummy but mystifying Kool-Aid.

I say all of this because Romain’s wines do, genuinely, remind me very much of Eric’s, and not just because it is standard practice to situate new young producers by producing a CV of the established names they’ve worked with in order to catch some adjacency bonuses.

Romain worked for Eric for 7 years, and started farming a hectare and a half of his own vines in 2018. He made his first wines in Eric’s cellar. The next year, he rented another 3 hectares in and around Lirac, next door. His Lirac rosé (which is what you have), in contrast to his Tavel, is solely direct-press — about three hours — and much lighter in color, less a rich deep ruby and more a quartzite, shimmery pink. In general, his wines are a little less about their actual color and more about shape and feeling I think about the different textures of cloth, from linen and silk to cashmere and velvet.

I would say that this, like a lot of pink wines I love and find worthwhile, can handle more than you might be giving it credit for. (This could apply to food, or emotional weight.) Consider doing more with it than pouring it over some ice cubes next to the pool, although if you open it at a barbecue and drink it with a hot dog you’re absolutely not going to have a bad time.

Wines like this are the well-made crewneck knitwear of wine, not the tailored dinner jacket. They say ‘luxury’ to me in ways that aren’t overbearing or full of pomp and circumstance, but do feel like the good life. Drink accordingly.