This is a slightly altered version of the April newsletter previewing the spring shipment of our wine club. Signups close on April 21st.

What wines do they grow in the Shire? What’s in the casks that barges carry upriver on the rushing Anduin? What is the terroir imprint of the volcanic soils of Mt. Doom?

This spring’s club shipment explores IMAGINARY WORLDS: the wines of Middle Earth.

This is something I’ve been playing around with for a while now that makes perfect sense to me in my head and that, based on every conversation I’ve had about it over the last two months, seems to require a little more explanation.

So, um, what does it mean?

Wine pops up in Tolkien from time to time, in the same way it pops up in the Old English sagas and medieval chronicles that he draws from to write his stories (and that, as a philologist, he studies). There are gilded cups in feasting halls, and bodies of water named for brandy, and references to wines “strong” or “golden” drunk by nobility in toasts or given as gifts. (Elves have a high tolerance and prefer mead.)

But Tolkein isn’t particularly interested in, like, how wine’s material culture might function in his world made of invented languages and place names and runic alphabets. And that’s probably not a bad thing! The more into the weeds you get, the more incoherent it starts to seem.

The Hobbits’ cozy 19th century English pastoral suggests dusty corked bottles in cellars and snifters of Madeira, but from what colonized island?

Gondor’s High Medieval drag (Byzantine?) implies sweet late-harvest Tokajs or pale co-ferments from monastery vineyards, but who are the monks praying to?

All of this is to say: we’re not going to worry about what’s “actually” in that glass in the screenshot.

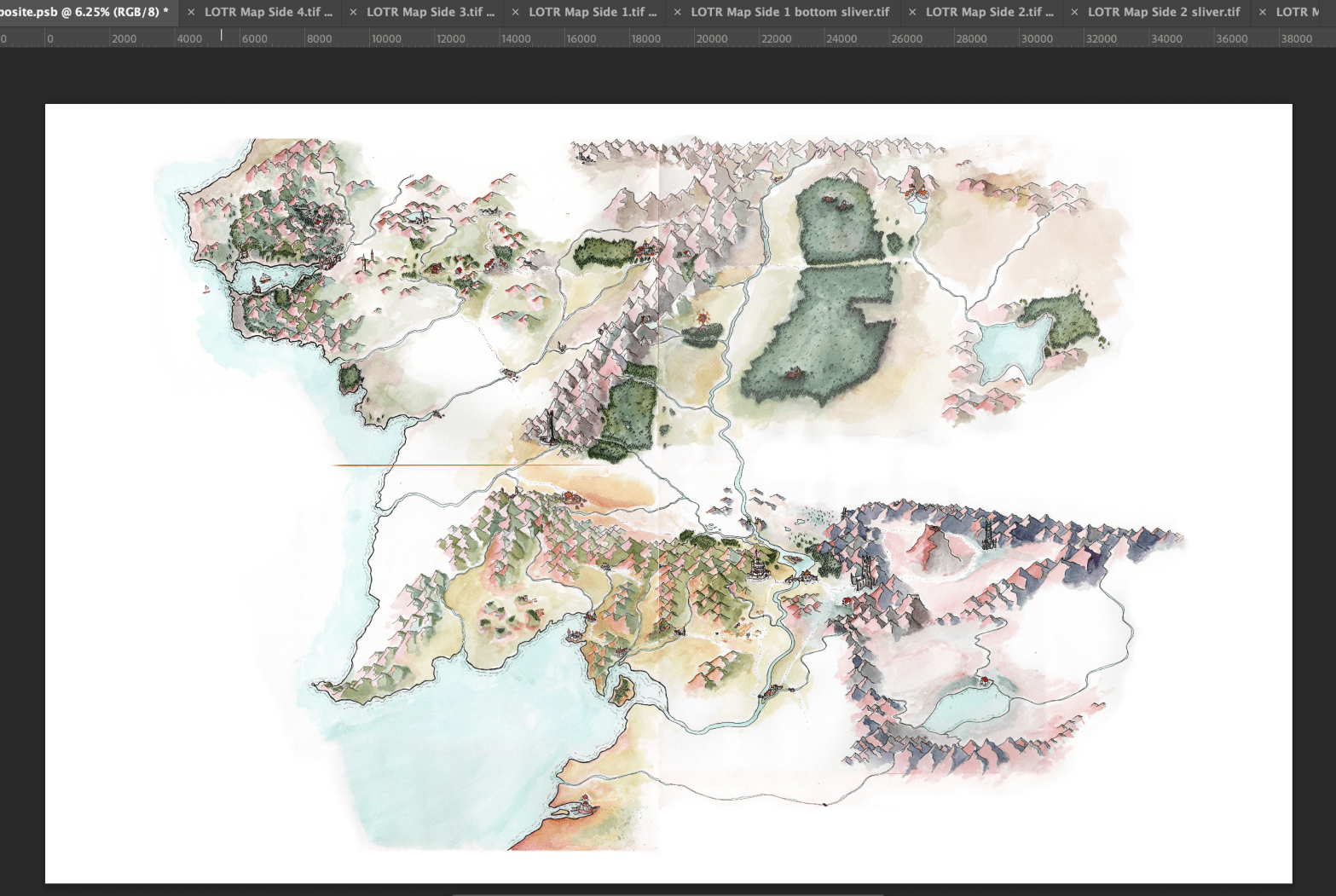

When I started drawing maps of wine regions, they looked like maps of imaginary worlds in the front covers of the books I’d read as a kid. The longer I drew them (real places), the more I got a sense for how wine regions worked. How you could tell by where the ground changed and the water flowed (and where the borders were drawn, and where money and power were situated) where interesting things might be happening.

The weird result, though, is when I go back and look at a map of imaginary places, I can just about see what the landscapes are like, and what kind of wine might grow there.

Four of the real landscapes in the club lineup, images courtesy of the growers’ instagrams: pergola terraces in in the Alps; a sherry pago in Andalucia; Lake Neusiedl in Burgenland; forests in the Little Carpathians

There are mountain passes and stone doorways with clouds wreathed beneath the vines; blinding white chalk flatlands at the edge of ancient harbors; a shallow, endless inland sea choked with reeds; forests and stone ruins on the edge of contested borders…

So, let me show my work for a moment here:

What wine grows in the Shire?

For me, it’s got to be something that feels like home base: cooling, refreshing, life-affirming.

Landscape is mild, rainy enough that you’ve never needed irrigation. There isn’t a bulk wine industry here with lots of consolidated large estates; plots are individual smallholdings, alongside vegetable gardens and family polyculture. We’re far away from major capitals and financial centers. We’re isolated from the water by coastal ranges, inland, on a river valley carved through rolling green hills.

Scrape the green and maybe there’s something ruddy and alive underneath: red clay, decomposed granite.

There’s a relationship you could draw to indigeneity, of people being tied to particular land, in the Hobbits, and also (spoilers for the ending of 1955’s Return of the King) the looming threat of the Scouring of the Shire. As far away from centers of power as you are, as isolated, sparsely populated, and peripheral, you can still be targeted by the kind of extractive, colonial capitalism that turns those green hills ash-grey.

For me, we’re in Itata & Bío Bío in southern Chile. We’re growing centenarian pais bush vines, and old honeysuckle and jasmine moscatel, and fermenting in everything from stone troughs to pinkish local hardwood to concrete eggs to cowhide.

We’re fighting fires fueled by industrial tree plantations funded by dictatorship, and honoring the Mapuche whose ancestors preserved their autonomy here for three hundred years by treaty and force of arms after ending the Spanish era of conquista.

The picture above is from Leo Erazo, whose “La Resistencia,” a pais bottling from a fifth of a hectare of vines planted in 1867, is one of the six bottles I’ve put together that trace real landscapes over the imaginary ones of Middle Earth. (Or three, if you get the abridged version).

There are, of course, a lot of options I’d hear out for any given place — this is all vibes-based, after all.

One thing I’ll say is that Western Europe is pretty deeply baked in to the way that Tolkien imagines his world (and to how fantasy as a genre has tended to most comfortably imagine worlds going forward from Tolkien). Things get more exotic, dangerous, and “darker” the further east or south you go, with detail yielding to blank spaces and uncharted wastes; the western continent across the ocean is an ultimate destination for ships full of people seeking eternal life; there are literal hierarchies of blood and breeding; etc.

It was kind of important to me not to just put the Shire in, say, Anjou, as pleasant and at-home as that landscape makes me feel (or, for slightly different movie-literalism reasons, New Zealand).

There’s maybe also something to be said for the way some wines don’t get to have landscapes attached to them: wines that are from places that aren’t talked about as “wine regions” (a natural winegrowing couple in Slovakia, maybe?); wines from people working outside of established appellations and bottling as “Country X table wine” (unfortified orange wine in sherry country?).

Meanwhile, industrial brand wine is just as often sold via the idea of landscape, places that don’t exist: perfectly manicured (chemically farmed, irrigated) rows, a Disneyland chateau.

Wine’s relationship to actual place is so often glazed over with nostalgia, abstracted to theory questions on WSET exams, leveraged for a sales pitch, or manufactured out of whole cloth.

Weirdly, I’m as much hoping to situate these wines in their actual places as I am excited to play around with superimposing them on Rohan and Mirkwood and the Misty Mountains. Maybe it’s just a way to square the circle?