A sip n’ paint at Plus de Vin, a wine bar off the Graham Ave L stop in Brooklyn, on Sunday afternoon, April 20. The next session will be on Sunday, May 11 [tickets].

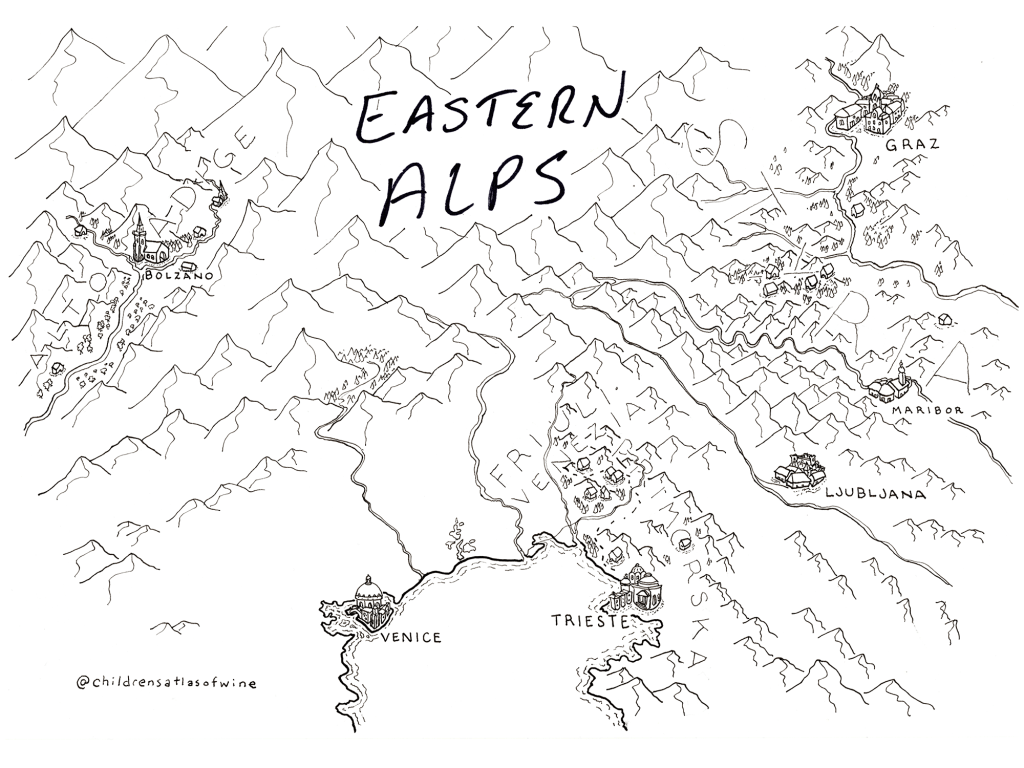

A spring sip n’ paint about the green, forested edges of the eastern Alps, featuring pinot grigio in a pink jacket, the best malvasia, and Steiermark sauvignon blanc for 4/20.

Ticket includes 5 wines, a wine region print for you to paint and take home, and an hour and fifteen minute wine class exploring living ferments, underrated places, and the people farming them.

A little more about what we tasted, who made it, and where it came from below:

(Previous sessions: “Over the Mountain“, “Under the Sea“)

NANDO, malvasia istriana, “Malvazija” [Collio/Brda]

Who? Andrej Kristančič (the winery is named after his grandfather), who started here 25 years ago.

The grape is malvazija / malvasia, which, like muscat, is a name given to a whole kaleidescope of ancient blue, gold, and pink varieties that shared in common, two millennia or so ago, the ability to ripen to high enough alcohols that they would survive a sea voyage across the Mediterranean. This malvasia, though, is malvasia istriana, a malvasia from Istria, the penninsula south of Trieste, which in its complicated saltiness and structure is maybe the most special of all of them.

The place is Brda (in Slovenia) or Collio (in Italy), both words that mean hills: the tiny borderland region of the Gorizia hills, crossed every day by thousands of vinegrowers. Andrej’s vines are on both sides of the border — about 60/40 between Brda and Collio.

What to do grill some fish (I don’t have a backyard but maybe you do), play lawn games (I don’t have a lawn, but –)

Bodega pairing Quart of olives, blue cheese stuffed if you’re into that.

TAUSS, sauvignon blanc, “Sauvignon vom Opok” [Südsteiermark/Styria]

Who? Alice & Roland Tauss. Roland had been making conventional wine for two deacdes before he began to profoundly shift the way he farmed (moving to biodynamics) and made wine in the cellar (energy, natural materials). He walks to the top of his hill every morning, his calves are crazy. Alice runs a yoga retreat next door. They’re part of a small group of Steiermark biodynamic growers called Schmecke das Leben, “Taste of Life”, along with Sepp Muster. (They’re neighbors, too—he can see the roof of Sepp’s cellar from his winery.)

The grape is sauvignon blanc! Old child of savagnin, sibling to chenin, half-sibling to a slew of other old grapes, born in the Loire but now spread throughout the world from Marlborough in New Zealand to the Collio in Italy to Sancerre in its birthplace and beyond, unmistakeable with its zesty, herbal streak, your friend with a really distinctive, um, laugh — but also, here in the Steiermark, maybe tasting different than anywhere else I’ve drunk it.

The place is The Steiermark (Styria), specifically the south Steiermark. The historical region of Styria is split today between southern Austria and northwestern Slovenia. It’s a green garden of sub-Alpine foothills, river gorges, local vegetables, a tiny amount of wine, mostly white with a couple of local specialties that taste good with schnitzel.

What to do drink on a spring day, pray for asparagus season

Bodega pairing Wasabi snap pea crispsS

SEPP MUSTER, morillon aka chardonnay, “Graf Morillon” [Südsteiermark/Styria]

Who? Sepp & Maria Muster, who live in a 300 year-old yellow house on the other side of the hill from Alice & Roland. Sepp took over the winery from his father in 2000 and already knew he wanted to push the farming (his father had never used chemical sprays) beyond simply organic, and to make wine in a similar spirit.

The grape is chardonnay, called morillon here. Poor chardonnay! Easy to grow, pretty neutral, it’s a people-pleaser, and it’ll taste like the company it keeps. Sweet kid, but needs better friends. Lots of people dislike chardonnay for how it’s been turned into chowder by industrial wineries, but vanilla-flavored popcorn butter is all winemaking, not the grape itself.

The place is next door to the Tauss’ place!

What to do put on Altman’s stoner, loopy 1973 remake of Chandler’s The Long Goodbye featuring a young, hot Elliott Gould as private eye Philip Marlowe — and keep an eye out for an uncredited turn by the Steiermark’s most famous son, Arnold Schwarzenegger, in his second-ever onscreen role, as “hood in Augustine’s office.”

Bodega pairing Microwave popcorn (fancy it up with some nutritional yeast or a cayenne – spice mix)

GRAWÜ, souvignier gris, “Ambra” [Alto Adige/Südtirol]

Who? Leila Graselli (GRA) and Dominic Würth (WÜ). Leila is Italian, Dominic is German, and Alto Adige…is both. After working together everywhere from Bordeaux to the Marche, they started their own project here in 2013 — they wanted their kids to grow up bilingual.

The grape is souvignier gris, a PiWi (rot-resistant hybrid) that can be grown without sprays or intervention. (More about PiWis, and hybrids in general, here.) Pink-skinned like pinot grigio, it’s been fermented and aged whole-cluster on the skins like a red wine.

The place is Alto Adige/Südtirol, an Alpine river valley that connects northern Italy to Austria and is historically bilingual, with residents speaking a mix of Italian and Südtirolean German. Also lots of apple trees.

What to do have a friend over to cook dinner / do date night with your partner, this wine is for food

Bodega pairing Chopped cheese!

corked :(( TERPIN, pinot grigio, “Slivi 2016” [Friuli-Venezia]

Who? Franco Terpin, an old-school natural grower who’s been working since the mid-90s.

The grape is pinot grigio aka pinot gris aka grauburgunder, pink-skinned mutation of pinot (more here). Pinot grigio was turned into an international commodity in the ’80s, and since then acreage under vine in northeastern Italy has more than quadrupled. If you want this pink-skinned grape to make crisp white wine, you’re going to have to ferment in temp-controlled stainless (first used for wine in 1962), ensure fast fermentation with inoculated yeast, and sterile filter before bottling. Before the days of crisp, vodka-soda pinot grigio, though, there were (and still are) wines like this: coppery or peachy or pink or ruby, textured and varied across a whole rainbow of color and style.

The place is just the other side of the current border from Nando in Slovenia, where “orange wine” as a category was rebirthed by natural winegrowers inspired to once again ferment on the skins, as their grandparents had.

What to do unfortunately, in this case, return the corked bottle to the store for credit or a fresh bottle that isn’t corked!

Bodega pairing Your evening plans ruined because of that corked bottle, it’s time for a consolation four-pack of Brooklyn Brewery’s Guinness collab brewed with fonio, which was in the bodega around the corner from me last month!

bonus bottle VINAS MORA, babic, “Kaamen” [Primorsten / Dalmatian Coast]

Who? Kreso Petrekovic, a Croatian-born natural wine importer who was stuck back home during the first COVID lockdowns and ended up meeting and partnering with a local grower, Neno Marinov to revive an almost defunct cooperative winery. Fun extra fact the label art was inspired by Sepp Muster

The grape is babiç, native to this little corner of the Dalmatian Coast, which can be thick-skinned, high alcohol and intense — here, it’s been treated very gently, to keep it fresh and beachy.

The place is crumpled terra rosa (crvenica), the reddish iron oxide limestone of the coast from here to the hills of Carso north of Trieste, little dry-stone walls with three-four plants each separating each plot, vines just feet away from the sea growing straight into the rock, looking at the Adriatic.

What to do crawfish boil!

Bodega pairing Utz BBQ potato chips

Finally, here’s what I read from The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity, by Kwame Anthony Appiah:

“Aron Ettore Schmitz was born in the city of Trieste at the end of 1861. His mother and father were Jews, of Italian and German origin, respectively. But Trieste was a free imperial city, the main trading port of the Austrian Empire, brought to greatness in the nineteenth century as it connected the empire to Asia. (“‘The third entrance to the Suez Canal,’ they used to call it,” Jan Morris, the English travel writer, tells us.) Young Ettore was, therefore, a citizen of the empire, which was rebaptized as the Austro-Hungarian Empire when he was six. Indeed, whatever the words “German” and “Italian” meant when he was born, they didn’t mean you were citizen of Germany or Italy. When, in 1874, Ettore arrived at a new school near Würzburg, in Bavaria, he was visiting a Germany that was younger than he was. The country had been created, a mere three years earlier, through the unification, under a Prussian monarch, of more than two dozen federated kingdoms, duchies, and principalities with three cities of the ancient Hanseatic League. A month or so later, they would be joined by Alsace-Lorraine, ceded to Germany by France at the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

“As for Italy? Ettore and Italy were practically born twins. The modern Italian state was created in the year of his birth, when Victor Emmanuel, King of Piedmont-Sardinia, was proclaimed King of Italy, united Piedmont-Sardinia with the Venetian territories of the Austrian Empire, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. So, like his father’s German-ness, his mother’s Italianness was more a matter of language or culture than of citizenship.

“Only in his late fifties, at the end of the First World War, did Trieste become what it is today, an Italian city. So Ettore Schmitz—Jewish by upbringing, a Catholic as a courtesy to his wife—had claims to being German and to being Italian, and never felt other than Triestine, whatever that meant exactly. Born a subject of the Austrian Emperor, he died a subject of the King of Italy. And his life poses sharply the question how you decide what country, if any, is yours.”

The chapter continues: Schmitz decided to write, effortfully, in Italian. He chose, as his pen name, Italo Svevo (roughly, “Italian Swabian”). A contemporary—Umberto Saba, another Jewish-Catholic writer from Trieste, once wrote, “Svevo could have written well in German; he preferred to write badly in Italian.” Italo Svevo befriended James Joyce, wrote an iconic avant-garde novel (La coscienza di Zeno), reveled in the ambiguities and street life of his home city.

Here is the end of the chapter:

“As a spumy wave of right-wing nationalism surges across Europe once more, we are bound to think about how fragile pluralism can seem. Few had a more acute sense of this than Italo Svevo, a man, who, during the First World War, was regularly summoned for interrogations by the Austrian authorities, and who found himself chafing no less under later policies of Italianization. Like Zeno, his greatest creation, Svevo was never happier than when walking among Trieste’s diverse neighborhoods; an inveterate ironist, he thrived on being sort-of Jewish, sort-of German, and, in the end, only sort-of Italian. For Svevo, who was at heart a man without country or cause, life was a dance with ambiguities. And when fascism convulsed Europe after his death, his kin were dashed against forces that detested ambiguity and venerated certainty—his Catholic wife, Livia, forced to register as a Jew, his grandsons shot as partisans or starved in camps.

“And yet, in the canons of our culture, Italo Svevo is still with us. […] To come to terms with Svevo’s complex allegiances is to understand that we don’t have to accept the forced choice between globalism and patriotism. The unities we create fare better when we face the convoluted reality of our differences.”