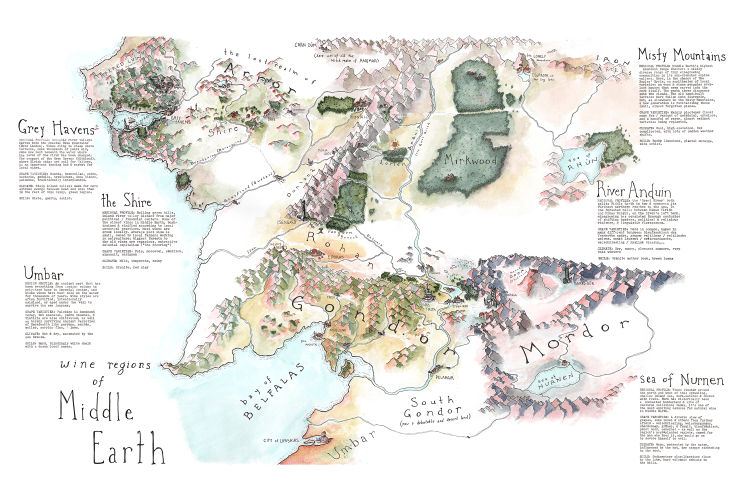

Welcome to the wine info page for CLUB shipment #2: IMAGINARY WORLDS! Preview the next shipment here.

What wines do they grow in the Shire? What’s in the casks that barges carry upriver on the rushing Anduin? What is the terroir imprint of the volcanic soils of Mt. Doom?

When I started drawing maps of wine regions, they looked like the books I’d read as a kid with maps of imaginary worlds in the front cover. And the longer I drew wine regions, the more I got a sense for how they worked. How you could tell by where the ground changed and the water flowed (and where the borders were drawn, and where money and power clustered like gravitational wells) where interesting things might be happening, wine-wise.

The weird result, though, is when I go back and look at a map of imaginary places, I can just about see what the landscapes are like, and what kind of wine might grow there.

Would you like to see what I see?

Hi everybody!

Thanks for joining me on maybe my highest concept wine box to date. This page is a digital guide to the bottles in your box, the landscapes they come from, and what you might want to do with them when you get them.

But first, a few touchstones:

These are wines grown and made by people, on a human scale. With the exception of the four friends at Envínate (who are a little more established and began in 2008) they all started bottling their first wines for themselves somewhere between 2015 and 2017, so they’re relatively new to the world — a taste of the future of their regions.

They’re farmed without chemicals, fermented with naturally present yeast and bacteria, and bottled without addition or subtraction (apart from maybe a little sulfur as a preservative).

That means they’re all also ‘natural wines’ — not necessarily always stretching to the wildest and weirdest edges of the spectrum, and in fact sometimes being a little more knit together — but always a butterfly in a garden, not one pinned in a display case. That means they’ll move and change with air and time, and show different sides of themselves as you get to know them.

On a practical level, that means you’ll want to keep them somewhere cool and dark so that they don’t bruise, fray at the seams, or grow second heads. Any fridge is probably better than no fridge, unless you have a cavern beneath your house. It’s also worth letting them settle down for a week or so after their journey.

Final practical tip, when it comes to pairing these bottles — pairing to meals, to bodega snacks, to emotional states, to the weather or the color of the sunset, to moments in time — remember that there’s a lot of good answers beyond my suggestions. There is no such thing as a wine emergency. If an ingredient isn’t in season, or you’re in a rental and have to drink out of mason jars, or you don’t have a Korean deli a block away from your house stocked with cutting edge 21st century snack food technology, give yourself a little grace. It’s enough to just be present with what’s in the glass.

Ok! I think that’s about it for the preliminaries — let’s talk about the wines in your box (and about how elves canonically can’t get drunk unless it’s mead):

Skip to: The Shire (pais from Leo Erazo) / The Misty Mountains (erbaluce from Monte Malleto/ Umbar, City of Corsairs (moscatel from Raul Moreno) / The River Anduin (sparkling rosé from Naboso)/ The Sea of Nurnen (pinot noir from Rennersistas) / The Grey Havens (field blend from Envínate)

THE SHIRE – LEO ERAZO, ‘LA RESISTENCIA’

The place Rolling green hills, inland river valley distant from major political / financial centers. Some of the oldest vines in Middle Earth, bush-trained and vinified according to local ancestral practices. Most wines are drunk locally. Average plot size is small, owned by local farmers working in polyculture. The biggest threat to those old vines is rapacious, extractive colonial capitalism: call it the Scouring of the Shire, or call it industrial forestry sponsored by dictatorship. More about the Shire / Itata here.

Why Itata? Places that feel like home base; that feel tucked away from the world and isolated from world-shaking events, but have their own stubborn sense of identity. Places with people who wouldn’t be tempted to use the One Ring for evil. Mild, green, verdant places. Important here too to undercut Tolkein’s tendency to map his imaginary world onto his own British colonial one, with a deep pastoral England at its center and dangerous, dark, barely intelligible creatures crowding the eastern and southern fringes. There’s no reason our wine mapping needs to do the same. Home base doesn’t have to mean ‘Europe by default’.

The wine A single plot of pais — the grape of the region, called ‘uva negra’, listan prieto, criolla chica, or misión. Often underestimated: called good for nothing more than jug wine for campesinos and communion wine for missionaries. In its pale color, resistance to drought, capacity to survive for centuries, salt & pepper minerality and sometimes surprising tannic structure it makes wines that sometimes remind me a little bit of Alto Piemonte or Gredos and can be quietly extraordinary. (Much like a hobbit in at least a couple of those ways.) This plot, a fifth of a hectare on sandy granite — a fifth the size of Gramercy Park, a fifth of the size of a major league baseball field — was planted to these vines in 1870. In 2023, it was burned over in the bush fires that ravaged Itata (fires that were made worse not just because of climate change but because of the industrial eucalyptus and pine plantations that are disrupting local ecologies and fueling bush fires). Today, Leo Erazo is in the process of nursing his vines, 155 years old, scarred and battered, back to life.

What to do Grill hot dogs at a festival celebrating, idk, the Mapuche victory that ended the Spanish era of conquista. Go to a park. Disrupt an ICE kidnapping afterwards.

Bodega pairing Chicharrones, chili tamarind snacks

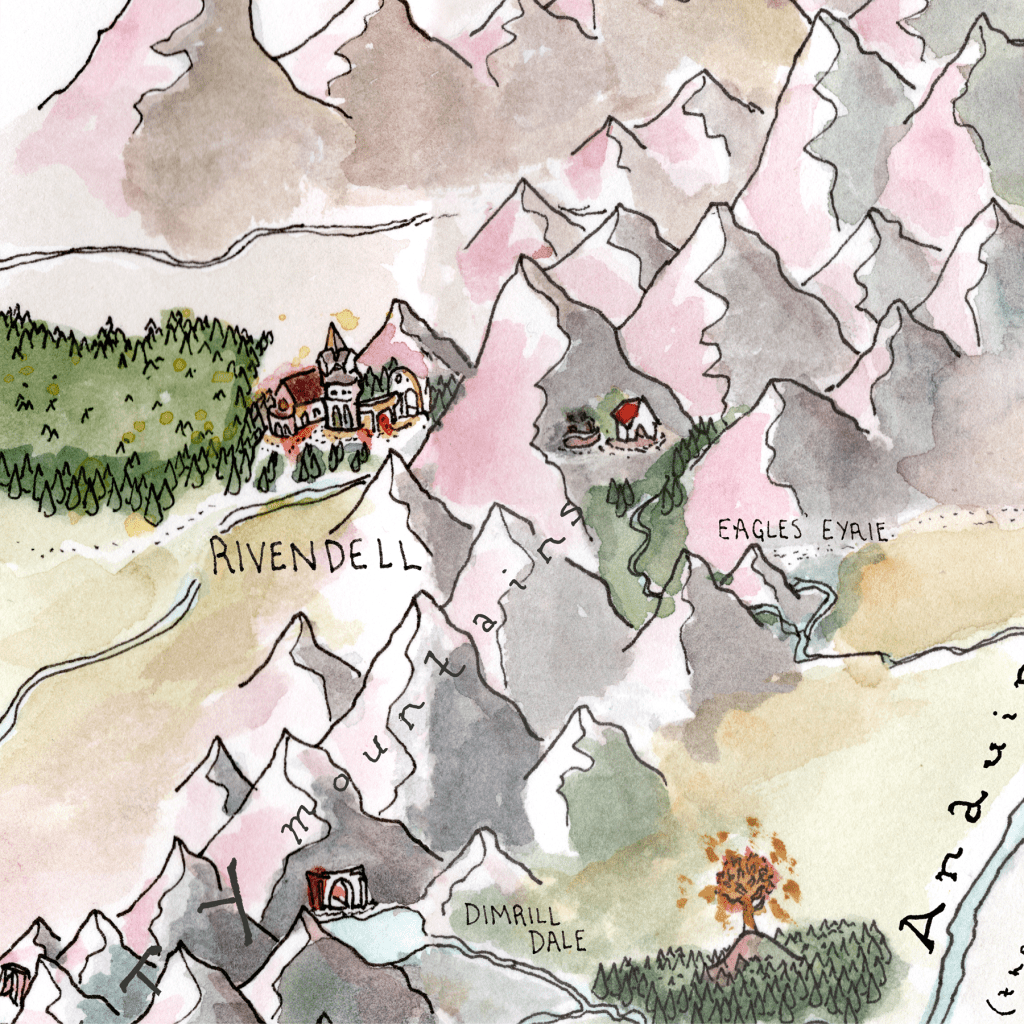

THE MISTY MOUNTAINS – MONTE MALETTO, ‘ERBALUCE’

The place Middle Earth’s highest mountain range shelters a wildly diverse range of tiny winegrowing communities in its sun-drenched alpine valleys. Here, in the shadow of the Eagles’ Eyrie, an amphitheater of local varieties trained on wood and stone pergolas overlook houses that seem carved into the rock itself. The peaks above disappear into the clouds. The old hand-built terraces have fallen into disrepair, but, as elsewhere in the Misty Mountains, a new generation is revitalizing these small, almost forgotten places.

Why Carema? Look at the Misty Mountains and you’ve got a number of possibilities for great mountain ranges with pockets of interesting winegrowing: the Pyrenées, the Sierra Foothills, the Andes. But in terms of their placement — a wall at the center of our map and both a barrier and a crossroads for the journey our heroes take, narratively central and full of myth and history — making them the Alps feels like a lay-up. In the Alps, you’ve still got plenty of options to pull from, from Alto Adige to the Dolomites to the Savoie. That said, 1) we just did Alpine regions on the Rhône river last wine club, so I felt compelled to stay away from France as much as possible here, and 2) I’ve been on a serious Alto Piemonte kick over the last few months, and if I’m living in my head on the Italian side of the big mountains it was really a question of wines that felt compelling and places that resonated with images from the books. In this case, the gateway to Moria — the doorway in the mountain — and the cloud-wreathed Eagles’ Eyrie were my touchstones. (The mountain eyrie is where the Lord of the Eagles takes Bilbo and the Dwarves after rescuing them from goblins in The Hobbit.)

Carema’s ancient terraces and stone pergolas, the way its houses seem built into the mountain itself, the peaks disappearing into the clouds, felt like a fit. (If you really run down this line of thinking it makes Rivendell, on the other side of the mountains, a stand-in for Geneva.)

The wine Transparent, mountain-spring erbaluce, an amber-colored native specialty of Torino often trained on pergolas. Up here in Carema, the pergolas are historically made of stone. While nebbiolo in a distinctively delicate mode is the star of this minuscule village tucked away where the Aosta river valley begins, it is joined by a little host of other obscure varieties, some of which are being revived from near extinction. Carema has a population of 800. The entire appellation is about 16 hectares of terraced vines that surround the village in a natural amphitheater. Just five or six other producers farm 1-2 hectares apiece. Gian Marco Viano is a former sommelier from down the mountain, one of a small group of recently-arrived young new producers who are revitalizing this nearly lost corner of the world, where most farmers were aging without heirs and selling to the local co-op. (He got here in 2014.)

What to do Battonage and aging in old tonneaux gives this a lot of texture and richness, in a scallop – lobster tail – sweetcorn – ajo blanco kind of way. Not quite cookout wine. Consider pairing with Alpine cheeses and a game night indoors, or drinking in the balmy evening after the sun has set, or blowing elaborate smoke rings with your enigmatic wizard friend. We’re serving Dover sole for two with a side of clam rice at the restaurant I’m running the program at this summer (which is also the reason these notes are so late) — this would be perfect with that.

Bodega pairing Sour cream n onion potato chips crushed into an egg n cheese on a kaiser roll. Does…your bodega sell caviar?

RIVER ANDUIN – NABOSO, ‘OPERA ROSÉ’

The place The ‘Great River’ both splits Middle Earth in two and connects its furthest northern reaches to the sea. In the forested hills between Minas Tirith and Minas Morgul, on the river’s left bank, winegrowing has persisted through centuries of shifting borders, political and religious violence, and linguistic florescence. Grape varieties are shared and named in many different tongues.

Why the Danube? The Anduin, like the Misty Mountains, is one of those features of the world map that vibrates with iconic resonances. As the “Great River,” it shares poetry and mythic history with the Mississippi, the Volga, the Rhine, the Gualdalquivir (or Wadi al Kibir) — and the Danube. Like all rivers, the Danube both connects and divides: it runs east from the Black Forest through Austria, goes between Vienna and Bratislava and through Budapest and Belgrade, and defines Romania’s southern border with Bulgaria before emptying into the Black Sea. Its name comes from the Celtic gods Danu or Don, from a proto Indo-European root it shares with other rivers like the Don, Dneiper, and Dniester (in Rgvedic Sanskrit, danu means fluid, dewdrop, and it becomes the word for river in languages like Iranian and Scythian).

The Danube stitches together of diverse wine regions, defining borders and overflowing them: the lizard-basking Roman terraces of the Wachau, the grüner and riesling hills of the Kremstal and Kamptal, the largest shallow seas in Europe, places where blaufränkisch is called kékfrankos, places where the most-planted grape is called feteascá.

Looking at Minas Tirith and Minas Morgul facing each other across the span of the Anduin and seeing Vienna and Bratislava reflected — one of the few places in Middle Earth that feels like a hard border, and one that has shifted over time with the abandonment of border outposts and ceding of territory — runs into one of the key ways, of course, in which mapping Tolkien onto central Europe gets fraught. Not only does Tolkien hard-code morality into his geography — some woods are just bad — but it has direction: further east means further into darkness, inscrutability, anarchy, and evil. People in our world have already followed that logic into casting the Soviet Bloc as Mordor (or, in a contemporary twist, Ukrainians calling Russian invaders ‘orcs’). Is it too easy to see the shadowy forests of Ithilien in the photo that Nadja and Andrej took on Christmas eve while hiking the forests around Sväty Jur’s Biely Kamen castle, above?

The wine A traditional-method sparkling rosé from one of my favorite producers in Central Europe. She’s German-born, he’s from Slovakia, they met and fell in love working in natural wine in Copenhagen and moved back a little less than a decade ago to make wine in a small village a 40 minute bus ride into the Little Carpathians from Bratislava. A different portrait adorns the label of each wine that they make, and a Danish artist friend paints a new version of the portrait every vintage. The “Opera” rosé blends direct-press saint laurent, blaufränkisch, and riesling — or svätovavrinecké, frankovka modrá, and ryzlik rynsky, as they might be known on the Slovakian side of the Danube.

I’ve written all of this and I just realized that the whole story is also kind of the dream of postwar Europe, a continent with shared histories and fractured borders able, after a century of blood and fire, to be able to move freely, across the continent, finding love while doing so.

What to do Open on a holiday morning; or with friends over for dinner in the part of the meal where everybody’s still standing up and won’t get out of the kitchen. Pair with shrimp cocktail.

Bodega pairing What is the shrimp cocktail of the bodega? Flamin’ Hot Cheetos? Bread and butter pickles? Is the appeal of a shrimp cocktail at aperitif hour its cold, briny sweetness or the sweet-sour heat of the sauce you dip it in? Have you ever shucked your own oysters?

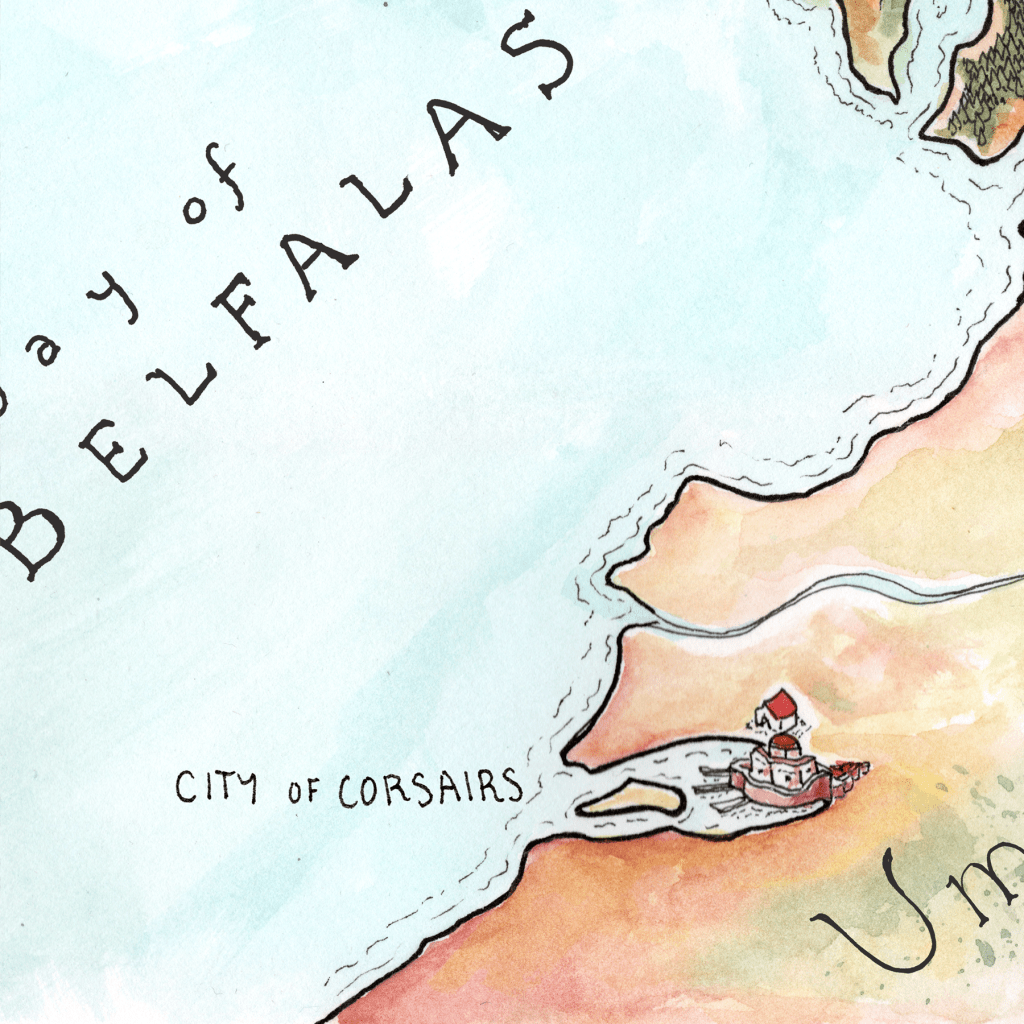

UMBAR, CITY OF CORSAIRS – RAUL MORENO, ‘LA PRETENSION’

The place An ancient port that has been everything from trading colony to privateer base to imperial center, and whose wines have been sold on the water for thousands of years. Wine styles are often fortified, intentionally oxidized, or aged under the veil to survive the sea journey.

Why Cadíz? It’s been a Phoenician trading post (Gadir), a Roman naval base (Gades), and an Al-Andalus port (Qādis), the point of departure for 300 years for Spanish ships bound for their colonies in the Americas, a perennial target of British raids (think “Sir Francis Drake singes the beard of the King of Spain,” 1587), and where the Spanish parliament governed from during the Napoleonic Wars. Other great port cities of the Mediterranean world and/or Iberian Penninsula — Porto, Valencia, Marseilles, Syracuse, Tripoli, Tunis, etc — could also be good Umbars. My immediate impulse, though — and this is an exercise based on vibes! — was sherry country: a wine itself defined by piracy and empire.

The wine A postmodern wine from sherry country — or an echo of the region’s past? Old-vine moscatel from the famous named vineyard (pago) of Miraflores in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, foot-trod whole clusters fermented in open-topped vats with gentle extraction (the cap is pressed down by hand for fifteen minutes once a day). After pressing the wine is aged in three 350L Cognac barrels, where it develops flor. Unlike sherry — whose recipe became set in stone as British merchant houses set up bodegas and set the region to a commercial standard they could transport across the world — this wine is unfortified and from a single vintage, rather than a solera. But it has a lot in common with the ancestral wines of the area, before sherry became Sherry.

What to do Embrace the cultural smorgasbord of a piratical port town! Delicacies from all over the wide world crowd your table. The obvious contenders are Andalucían: you’ve got your brined olives and jamón ibérico, your Marcona almonds, your red peppers in oil, your membrillo y queso, your honey and dates. But you could equally draw inspiration from Morocco, Greece, Turkey or Egypt. This is a wine that really embraces salty cured fish, olive oil, pickled things, and pungent spices.

Bodega pairing Smorgasbord on a budget: gherkins, hummus, pita chips, canned tuna.

MORDOR / SEA OF NURNEN – RENNERSISTAS, ‘PI-NOH!’

The place Vines cluster around the north and west of this sprawling, shallow inland sea, dark-watered and choked with reeds. Núrn has historically been a contested borderland and site of cultural collision; today, it’s one of the most exiting nexuses for natural wine in Middle Earth. There’s a diverse slew of grapes here, some local and others further afield — including the region’s most planted variety, name for the man who bred it, and who would go on to devote himself to evil.

Why Burgenland? On the one hand, if you’re going to put together a Lord of the Rings wine regions map, you’ll want to intersect with the places that the books lavish attention on, the places our heroes travel through and that our characters populate (you’re going to want to see the Shire!). On the other hand, though, there’s that undeniable fascination I have with the places that are just names — that gesture at a wider world beyond the plot, the little notations that are scattered across Christopher Tolkein’s map for the Lord of the Rings first edition giving flavor to places we never get to see. In little red text below South Gondor (Harondor): now a debatable and desert land. To the far north, next to a ruined fortress labeled Carn Dûm: Here was of old the Witch-realm of ANGMAR.

What’s up with Rhûn, anyway? Where did the blue wizards go?

Sometimes, the topography of a bit of the map like that immediately reminds me of a real-world wine analog. The inland sea of Nurnen, in Mordor far to the south of where Frodo and Sam duck and hike through, bracketed by mountains, staring out over an endless plain to the east, with an even bigger inland sea to the north . . . I look at it and immediately see the great central European lakes of Balaton and Neusidl (first and second largest on the continent).

The Neusidlersee, curled like a comma around the border between Austria and Hungary, stretches over 122 square miles, but it’s shallow enough that even at its deepest that I could walk across it and it would only come up to my eyebrows. Backed by the schist mountains of Leithaberg, it faces the beginning of the Pannonian Basin and the brown expanse of the eastern European steppe. Like a lot of borderland wine regions, it scrambles the dynamics we take for granted for when we talk about what the wines of a particular “country” are like. Austria may be grüner and riesling land, but here, we’re warm enough to grow a ton of red wine alongside a seasoning of white grapes like welschriesling or furmint: everything from pinot noir and cabernet franc to st. laurent and blaufränkisch, as well as a st. laurent x blaufränkisch cross that Austria has made its signature, and one that’s worth talking a little bit more about. (Even though our wine is made from pinot noir.)

Originally called 71–2, and then rotburger, it was one of a number of early crosses made in 1922 by Dr. Freidrich Zweigelt at Klolsterneuburg, who would later, from 1938 to 1945, be the director of the experimental vinebreeding station there. (Sorry, I of course mean the Höhere Bundeslehranstalt und Bundesversuchsstation für Wein-, Obst- und Gartenbau.) After the world war, it was one of the 2,800 vines around the station that survived, and its potential was recognized by another Austrian viticulturalist, Lenz Moser, who began selling propagated vines under the name Blauer Zweigelt in 1960, in the doctor’s honor. By 1975, it was named in Austria’s official index of quality grape varieties, and today it’s the most-planted red grape in the country.

If the years of Zweigelt’s tenure at the institute is making any little alarm bells go off in your brain, they should. Zweigelt was an early and enthusiastic Nazi — he joined the party in 1933, when it was still illegal in Austria to be a member, and his 1938 appointment as director of the institute happened in train with Austria’s absorption into the Greater German Reich. Afterwards, he informed on colleagues and led a staff purge in service of making Klosterneuburg a National Socialist stronghold. He also edited a magazine, Das Weinland. He had a lot of ideas about how vine breeding could be politically Aryan.

Austria’s postwar decades involved a lot of intentional forgetting. Zweigelt himself, insisting after the war that he was a mere ‘follower,’ would receive a presidential pardon, his charges of warmongering, treason, and denunciation reduced to “oratorical lapses”. He lived out the final two decades of his life quietly in Graz, on a reduced pension.

The history of zweigelt, which was being successfully promoted as an Austrian specialty by trade boards and PR firms when I came up in wine, resurfaced in 2018, and I’ve glossed most of the story from a 2019 Grape Collective piece by Valerie Kathawala (read here), as well as a translation of an article in German for FINE magazine by Dr. Daniel Deckers posted over at JancisRobinson.com (read here).

And not to be too cringy or on the nose about it, but in addition to the “big lake” of it all, there’s something about how Núrn intersects with the good & evil political resonances of this story that chimes for me. Canonically, Núrn has been subjugated by Sauron. Its inhabitants work the fields next to the ‘bitter sea’ to feed Mordor’s armies. If we’re going to be drinking at the end of the Third Age and into the Fourth, we get to do it after Aragorn is crowned Elessar, High King. We get to drink Núrn after they’ve been freed by Aragorn, who goes on to do some land reform. And that feels of a piece with the way that Burgenland, a region on a border that has at various points in the 20th century been a militarized one, hardened by tank emplacements and barbed wire, now feels like one of the most exciting clusters of natural wine community on the planet.

The wine 100% pinot noir. Not the most quintessential red grape of Burgenland (that would be blaufränkisch — kékfrankos in Hungary), or Austria’s most-planted red (that would be rotburger, more commonly known by the name of the grape breeder and enthusiastic Nazi who made the cross) — but such an undeniable bottle that I had to grab it for this pack. The Rennersistas are Stefanie, the ringleader, and Susanne, joined by little brother Goerg. Their first vintage under their own label was in 2015, carrying on the work of their father (whose wines and farming were quite a bit more conservative). Before returning home, Stef worked with both Tom Lubbe (of Matassa, iconic natural winegrower in the Roussillon) and Tom Shobbrook (one of the three pioneers of natural winemaking in Australia alongside James Erskine and Anton van Klopper). Her pinot is infusion-style, with a short maceration before pressing to finish fermentation in big 500L casks, where it settles into clarity over the course of a year and a half.

What to do Sear a duck breast, trick your Burgundy-loving friend. This also would be good anniversary wine to open with someone you love — or a good way to celebrate the overthrow of something tyrannical and the building of whatever world comes afterwards.

Bodega pairing Chicken & lamb gyro on pita from Late Night Stars Deli ($12.99, white sauce hot sauce please), Swedish fish

GREY HAVENS – ENVÍNATE, ‘MISTURADO’

The place Dramatic river valleys carved into the coastal Blue Mountains (Ered Lindon). Vines cling to steep slate terraces, some thousands of years old, some now lost beneath the water where the level of the river has been changed. The seaport of the Grey Havens (Mithlond), where Elvish ships set sail for Valinor, is an important trading hub and market for local wines. Steep inland valleys make for more extreme swings between heat and cold than in the rest of this rainy, green region.

Why the Grey Havens? One image above all leads me from the Grey Havens to Galicia: the Roman-era terraces in Ribeira Sacra, once vines on the slopes of the river Sil, now drowned below waters that have changed after a hydroelectric scheme during the last decade of the Franco dictatorship saw a network of dams built throughout the region. (Galicia supplies something like 10% of Spain’s electricity; read this evocative 2017 El País article about drought revealing villages and valleys long disappeared. The first line: “Somebody has laid flowers at the hanging tree.”)

There’s also the geography of the Grey Havens — northwest, mountainous, facing an ocean with a land to the west. The jagged coastline isn’t quite the fjords and estuaries of Rías Baixas, but it’s as close as the Middle Earth seacoast gets. In LOTR canon, the Blue Mountains and Lindon are the last eastern remnants of Beleriand, which sinks into the sea after the War of Wrath, at the end of the First Age. It is a “green and forested land.”

This is more about landscape and water, in other words, than it is about Elves, who are mostly unaffected by beer and wine and drink “miruvor, the cordial of Imlandris … a warm and fragrant liquor,” which seems to be mead infused with flowers and herbs.

The wine A throwback: a century-old parcel co-planted to red and white varieties, fermented together and bottled without addition or subtraction. (The watercolor labels from Envínate, as opposed to their regular solid-color text ones, are a series of single-parcel ancestral bottlings that they make without any sulfur, a little wilder and less controlled than their usual minimalist approach). The white grapes in this old plot are varieties like godello, treixadura, albariño, and doña blanca. As for the reds, apart from mencía, which has become the main variety grape of Ribeira Sacra over the last two decades of its renaissance as a wine region, you’ve also got rare locals like mouraton and brancellao as well as deeply-colored crosses imported in the early 20th century for bulk production, like alicante bouschet and grand noir de la calmette. The four friends behind Envínate have been working for about a decade longer than the other producers in the shipment — more than enough time to have become emblems of a new wave of terruño-focused Spanish winemaking.

What to do I think of reds from Ribeira Sacra as doing figure-8s inside a playing field bounded by syrah, cabernet franc, and pinot noir: sometimes arcing more towards the smoky-peppery-meaty side of syrah, sometimes more towards the autumnal, herby tones of cabernet franc, sometimes emphasizing the bright red-fruited freshness and potpourri of pinot.

Here, I think we’re moving further into darkness: rain pattering against the window, deep leather armchair, a forest outside the witches you consult say will come to you at the hour of your doom, a stack of good books.

Maybe make a brisket?

Bodega pairing Chopped cheese