Note: this originally appeared as a sidebar explainer in the December 2022 newsletter. Sign up for future newsletters here.

What’s a hybrid?

Think about the first grape variety that pops into your head.

Cabernet sauvignon, maybe. Sangiovese, yep. Assyrtiko, mencía, pineau d’aunis? Check. Nosiola, sumoll, tsolikouri? Now you’re just showing off.

All of them, and a couple of thousand more of the commercially planted grape varieties that go into most if not all of the wines you’ve tasted in your life, are cultivars of a single species:

V I N I F E R A

Vinifera is a vine native to Central Asia, family vitis, domesticated by humans ten thousand or so years ago in the Caucasus.

Ways we know it happened there: genetic diversity of species is highest near point of origin, as a general rule, and Georgia alone is home to over five hundred different named grape varieties, something like a sixth of the world’s total.

Also, that’s where our earliest evidence of winemaking is, in the form of tartaric acids and grape skin traces on pottery shards buried in archeological sites from Georgia to Armenia to northern Iran dated to 8,000+ years ago.

(Fun fact about human domestication of grapes: in the wild, vinifera vines are often, although not always, sexed male or female. Of the vinifera cultivars people named and propagated, over 95% are hermaphroditic—they have all of the relevant parts, and can self-pollinate without the need of another vine. Useful!)

V I T I S

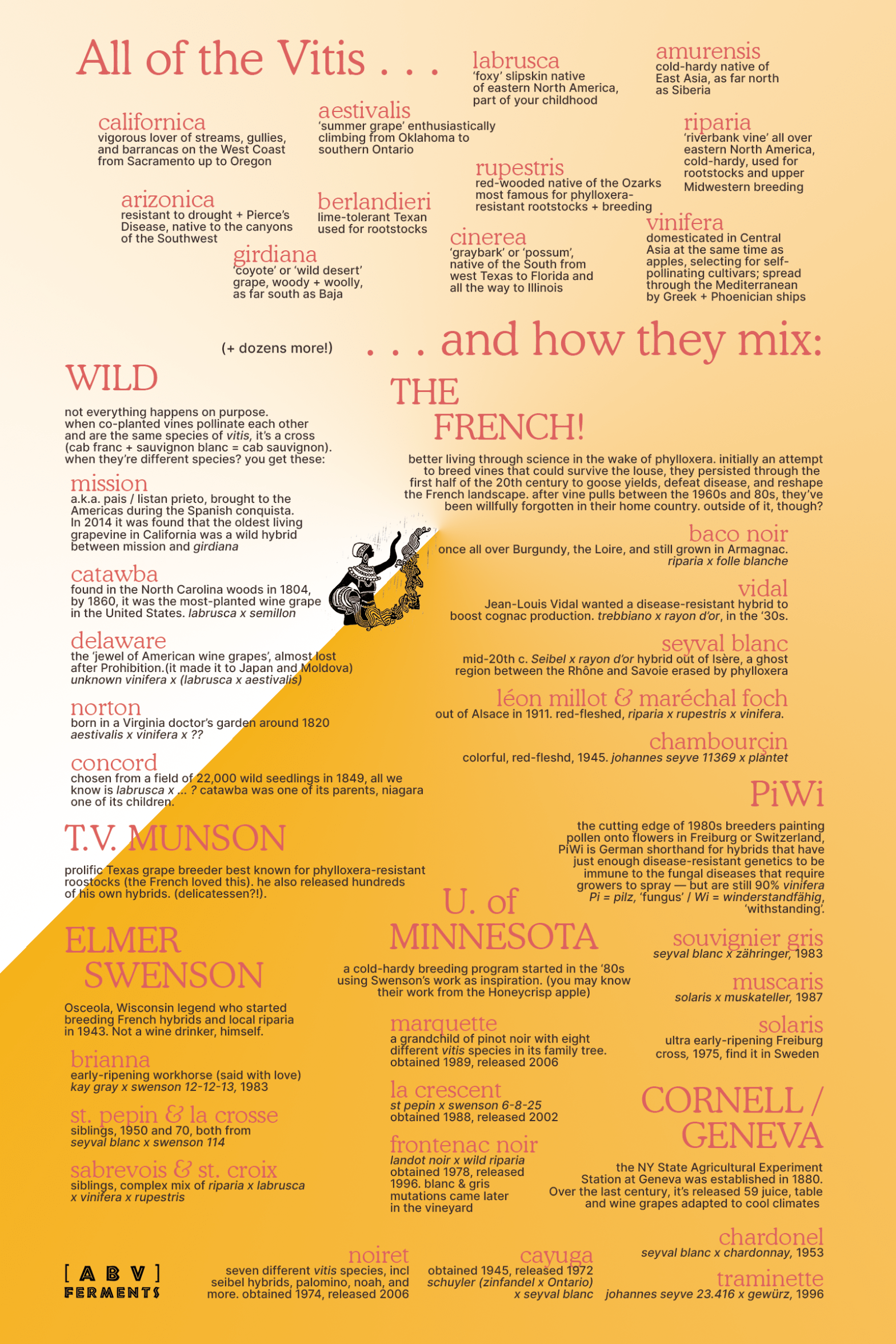

But like I said: vinifera is just one species of vine in a family. The only species endemic in Europe and western Asia, as it turns out. But there are four or five dozen other vitis species around the world, mostly in North America and southeast Asia.

There are cold-hardy riparia vines on Wisconsin riverbanks, and muscadine with golfball-sized fruit in the Florida panhandle. There’s heat-loving arizonica in the canyons of Chihuahua, and rot-resistant amurensis in the forests of Manchuria. There are rupestris and labrusca, berlandieri and aestivalis, californica and piasezkii and fifty-odd more.

Cross v. Hybrid

Small biology word corner: Crosses happen inside of species, like labradoodles. Or, if we’re talking grapes, something like cabernet sauvignon (parents: sauvignon blanc, cabernet franc). Hybrids, on the other hand, are crosses that happen between species.

Hybrids can happen both accidentally and on purpose (and when on purpose, at different times and places for different reasons)

Accidentally: catawba, a hybrid of a wild labrusca vine and sémillon, was found growing wild in the North Carolina woods by an innkeeper in the early 19th century. High-acid, ruby-skinned, with mulberry aromatics, it became core to the country’s domestic wine industry, centered around the Ohio River valley, and by 1860, it was the most-planted wine grape in the United States.

On purpose: frontenac noir was bred in 1978 at the University of Minnesota’s cold-hardy vine program by three scientists who took the pollen of a riparia vine found growing wild near Jordan, Minnesota and painted it by hand onto the flowers of a complex French hybrid from the 1930s growing in their test vineyard that had the genetics of eight different vitis species in its lineage.

Why does this matter?

Hybrid vines have a history that goes back, for our purposes, to the colonial encounter in the Americas. (There’s probably some stuff along the Silk Road, but the story there is even older, less well-understood, and so far, doesn’t have as much of an impact on the wine in your glass.)

Whether they were bred on purpose or found thriving in the wilderness having been born by accident, the best case scenario is the same: new and old come together to create offspring that are better adapted to the world than their parents, plants that want to grow exactly where they happen to be.

Vinifera, on its own, is fragile in a lot of places it didn’t come from (this includes northern France!). It’s vulnerable to diseases, many of which were introduced from other places during the 19th century, when capitalism got fast enough to start disrupting biospheres in earnest. It can get wiped by frost, or choke out in drought. Grow vinifera in a lot of places, from Virginia to Champagne, and you’ll likely find yourself having to gas up the tractor to spray something, organic or very much not, on your vines — just to keep them alive.

That said, multi-vitis varieties have an incredibly fraught and reviled history.

In Europe, they were bred as part of the response to the mass extinction event of phylloxera, which vinifera was uniquely vulnerable to. (There was a ton of baco noir planted in the Loire through the 1950s, for example.) But they were seen as suspicious interlopers displacing paysan winegrowing tradition, and/or put to work as tools for ultra-scientific industrial grape production. Eventually, they were uprooted en masse by law. They survive in folk sayings that claim drinking hybrid wine will make you blind, and are widely prohibited in the EU. (This isn’t stopping growers like Nicolas Jacob, in the Jura, whose field-blend plot of hybrids he calls an ‘act of resistance’ against the entire phytochemical industry, whose profits would collapse if hybrids stopped being classed as inferior.)

Meanwhile, in the United States, hybrids and native vines got irrevocably associated with jelly (Concord!) and sweetness (muscadine!). Prohibition broke the country’s relationship to alcohol (if it wasn’t broken to begin with), wiped out generational knowledge, and led to the consolidation and industrialization of the beer and wine industry.

The result was the erasure of local beverage cultures and histories, and the gatekeeping of wine behind a Europhile inferiority complex. Hybrids were just one of the embarrassing homegrown secrets you forgot or actively disavowed once you moved to the metropole, in body or in spirit, to Get Culture.

Real wine was a scarce, distant luxury. The vines growing in your backyard were beneath notice.

But—what if—the plants you tended for winemaking were adapted to their landscape and capable of weathering a shattered climate? What if you didn’t need to spray or irrigate or fertilize? What if wine came from what grew locally, in abundance?

What if things were starting to change?

Was this helpful? If you learned something from this, consider supporting the project via our patreon!

Below, you’ll find a list of the wines from multi-vitis and native vines that we’ve tasted together in classes and seminars, as well as a few I can recommend from my personal drinking:

HYBRIDS GREEN + GOLD + PINK

CHËPÌKA, catawba, FINGER LAKES rosé

CHËPÌKA, catawba, FINGER LAKES 2021 pet-nat sparkling

CHËPÌKA, delaware, FINGER LAKES 2020 classic-method sparkling

DEAR NATIVE GRAPES, delaware, FINGER LAKES 2021 skin contact

WILD ARC, itasca HUDSON VALLEY / FINGER LAKES skin contact

LA GARAGISTA, frontenac gris & la crescent, “Harlots & Ruffians” CHAMPLAIN VALLEY

LA GARAGISTA, la crescent, “Vinu Jancu” CHAMPLAIN VALLEY skin contact

OYSTER RIVER WINEGROWERS, sevyal + cayuga, “Morphos” FINGER LAKES / MAINE pet-nat sparkling

COMMON WEALTH CRUSH x JAHDÉ MARLEY, vidal + petit manseng, “Love Echo” SHENANDOAH VALLEY

SPINNING WHEEL, chardonel, vidal, valvin muscat, “You Can Have It All” VIRGINIA

PLĒB, vidal, seyval, traminette, “Appalachian Classic” APPALACHIA ancestral sparkling

AMERICAN WINE PROJECT, somerset seedless, “We Are All Made of Dreams” DRIFTLESS AREA pet-nat sparkling

AMERICAN WINE PROJECT, saint pepin, “Modern Optimism” DRIFTLESS AREA

BOHN, souvignier gris ALSACE 2020 skin contact

GRAWÜ, souvignier gris “Ambra” ALTO ADIGE skin contact

JOSEF TOTTER, muscaris STEIERMARK

JOSEF TOTTER, souvignier gris, “Severin” STEIERMARK skin contact

HYBRIDS PLUS FRUIT

COMMON WEALTH CRUSH x JAHDÉ MARLEY vidal, manseng infused w/ foraged pawpaws, “Love Echo” SHENANDOAH VALLEY pét-nat

FRUKTSTEREO, apples, pears, plums, solaris grapeskins, “The Fruit Pét-Nat Formerly Known As Cider” MALMÖ fruit pét-nat

HYBRIDS BLUE + PURPLE

LA MONTAÑUELA, frontenac-based field blend, “La Noche y Tú” CHAMPLAIN VALLEY co-ferment

LA MONTAÑUELA, marquette, “Rocio” CHAMPLAIN VALLEY

KALCHE, marquette, “Mimeomia” FLETCHER, VERMONT rosé

WILD ARC, thirteen varieties, “Amorici Vineyard” WASHINGTON COUNTY/HUDSON VALLEY co-ferment

EARLY MOUNTAIN, chambourçin & vidal blanc, “Young Wine” SHENANDOAH VALLEY, VIRGINA co-ferment

PLĒB, marechel foch, seyval, traminette, hickory shag bark “True Player” APPALACHIA co-ferment under flor

AMERICAN WINE PROJECT, concord + marquette, “Wisco Nouveau” DRIFTLESS AREA

AMERICAN WINE PROJECT, frontenac, “Water + Sky” DRIFTLESS AREA

NORTH AMERICAN PRESS, baco noir, “The Rebel” SONOMA

AZORES WINE COMPANY, isabella, “Prohibida” AZORES

4 thoughts on “Grape Files: ‘What’s a hybrid?’”