A monthly class series exploring the outer limits of Spanish wine hosted at Tin Parlour, a conservas wine bar in the East Village.

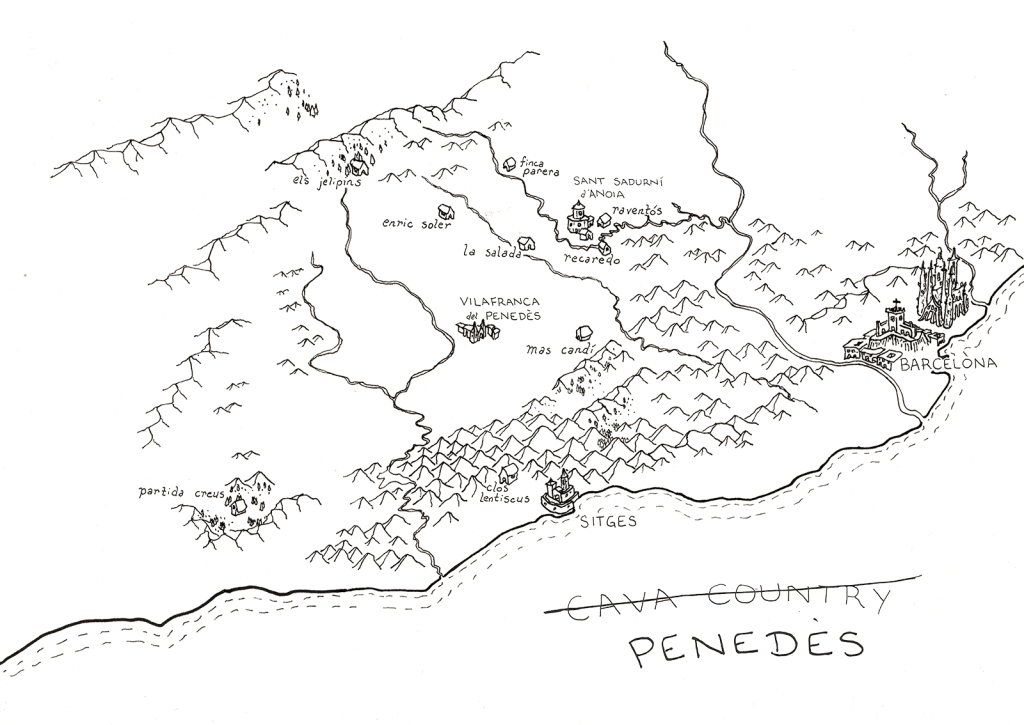

May’s session, ‘Cava Country’, was held on Thursday the 23rd. See below for notes on the wines we drank, and a map of the landscape they were grown in.

Cava is pretty immediately recognizable as a shorthand for bubbles, right? Cheap ones, probably, a bottle you wouldn’t feel bad about putting orange juice in after grabbing it off the shelf on your way to a friend’s brunch party.

But cava is more than that $14ish bottle of, let’s say, Freixenet Cordon Negra — it’s a landscape. Almost all of it is grown in a single place.

While we are fond in wine of talking about the impact place has on what’s in your glass (terroir, “wine is made in the vineyard,” soil type), there are less ethereal, squishy, romantic ways that landscapes get shaped and in turn shape the bottles you’re drinking. Money, and what it wants, ends up mattering. A lot. And whole places can get get transformed towards commercial ends.

Cava Country — an agricultural landscape in the river valley over the hill from Barcelona once planted to olives and orange groves and grain that has been turned into a factory floor for wall to wall machine-harvested vineyards servicing a highly consolidated sparkling wine industry — tells this story in spades.

But it tells another one, too — a flowering, over the last two decades or so — of some of the most deliriously exciting, varied, weird wines in what I guess we’ll call Spain (but is really Catalunya).

The children and grandchildren of the grape growers in that valley are, for the first time in generations — or ever — bottling wine for themselves from the vines they tend.

And Cava Country is finally becoming what it was, secretly, all along: a wine region called Penedès.

What we drank

Freixenet cava, “Blanc de Blancs” // Recaredo corpinnat, “Terrers” 2018 // Mas Candí xarello, “QX” // Joan Rubio xarello, “Esencial” // Ramon Jané rosé pet-nat, “Tinc Set” // Clos Lentiscus blanc de blancs brut nature, “Greco di Subur” // Finca Parera clarete, “Fins als Kullons”

More on what we tasted and why it matters

Photo credit Emma Fleming (mine was backlit)

Freixenet, cava, “Blanc de Blancs”

Freixenet is to cava what Big Macs are to hamburgers. A brand founded by the union of two locally prominent landowning families in 1914 in Sant Sadurni d’Anoia, it produces over 100 million bottles of cava per year yet owns only 123 hectares of vines. The rest of the grapes are purchased from a thousand or so growers in Catalunya and throughout the rest of Spain.

In 2018 a controlling interest was acquired by a big German sparkling wine company, Henkell, which began operations in 1856 in Mainz by building a “champagne factory”, which was the style at the time. (Notable bon vivant and Holocaust architect Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, married into the family in 1920 and was the company’s wine sales representative in Berlin for most of the decade.)

Today, Henkell-Freixenet is a division of Geschwister Oetker Beteiligungen KG with annual sales of 2.5 billion Euros, alongside other divisions in baked goods, chemicals, hotels, and financial services; its website proclaims that it “serves every tenth glass of sparkling wine in the world.”

The grapes, according to the tech sheet, are xarello, macabeo, and parellada: the three classic white grapes of cava.

They will have been purchased from growers throughout the region and farmed chemically, with some degree of herbicide and pesticide application; only about 10% of the farming in D.O. Cava is certified organic. Fermentations are temperature-controlled and managed with strains of yeast cultured in-house: the goal is consistency and efficiency at an industrial scale.

This has implications for how the wine tastes, of course (and, more importantly, for the landscape it’s farmed in), but it also shows up in pricing and logistics (where do I find this, and how much does it cost when I do?).

The bottle of Freixenet cava we tasted was purchased at an East Village liquor store for under $15 out of a fridge where it sat alongside Veuve Cliquot Yellow Label and André California Champagne.

Recaredo, corpinnat, “Terrers” 2018

The wine we tasted next to the bottle of Freixenet shows, in many ways, the complications lately around the idea of Cava, what it is, and who makes it.

Recaredo was founded in 1924 by a professional disgorger in Sant Sadurni d’Anoia who worked in the town’s booming sparkling wine industry and named the house after his father’s nickname. (Back then, the wines were called xampan — x pronounced as ‘ch’.)

These days, Recaredo is a medium-sized, well-regarded grower producer: the house makes wine from the fruit it farms, 80 hectares in biodynamic certification in parcels around San Sadurni d’Anoia, with around a quarter million bottles a year annual production of sparkling wines that are single vintage, aged on the lees for an unusually long amount of time, hand-disgorged, and made only from the region’s local varieties.

The wines sit on the shelf for around $35–45 — eye-wateringly expensive if your comparison point is that $15 bottle of Freixenet, cheap if your competition is your average single-vintage grower champagne.

And until a handful of years ago, Recaredo’s bottles were cava, too.

The Cava D.O.’s domination by a small number of large industrial producers (Freixenet and Codorníu account for two-thirds of the D.O.’s production) has historically made it tricky for smol guys ™ making wine in a different way to communicate quality via ‘Cava’ on the label.

A handful of years ago, a little pack of them founded a voluntary brand association called Corpinnat, a portmanteau of Latin and Catalan: nat (born) in the cor (heart) of pinna (Penedès).

Membership required a combination of greater specificity, better farming, and quality commitment: organic certification (or being in conversion to organics); using the indigenous varieties of the region, including a couple ancient grapes like sumoll and cartoixa vermell not allowed in the Cava D.O.; and being from a delimited core of the cava’s 19th century growing area (instead of the Cava D.O.’s theoretical ability to be from basically anywhere in Spain).

There were a few other bells and whistles, like longer lees aging, a requirement that you make your own wine instead of buying finished wine on the open market, and harvesting by hand.

It was originally proposed as an additional brand Cava D.O. producers could opt to add to their labels. After some years of behind-the-scenes back and forth, the conseja regulador of the D.O. basically told them: go ahead, but if you put ‘Corpinnat’ on the label, you’re out of the D.O.

In 2019, the Corpinnat growers called the bluff. Ever since, a shortlist of what were once the most recognizable quality names in Cava Country to, say, a mid-2010s NYC baby somm — Recaredo, sure, but also Gramona, Castellroig, and Raventos, who left the D.O. for its own reasons in 2012 — have no longer said Cava on the label.

The Cava D.O., for its part, has tried to introduce internal reform to solve the problem of “how do we communicate quality in a world where most people expect cava to be $14 industrial wine”, debuting a tiered system of classification with subregions, longer minimum lees aging, and, at the highest level, single vineyard ‘grand cru’ designations. The wines in this scheme (still a very small piece of the big cava pie) will require organic certification starting in 2025.

But whether you’re trying to give credit where credit’s due to the folks still inside the D.O. making real, well-farmed sparkling wines, or highlighting those who left it, the problem of what cava is, really — and the degree to which you explain it to someone who just wants to drink some good wine, please? remains.

And for some people, no matter how much we try, cava — like xampan before it — will keep on being the photoshop or kleenex or tylenol of Spanish bubbles.

(Just look at how the wine I just spend 1,000 words explaining is listed at this Brooklyn wine shop):

Mas Candí, xarello, “QX”

“QX” was the first of two still white wines made from a grape usually blended into cava that we tasted to see what it could do on its own.

Another member of the Corpinnat gang, Mas Candí is a small collective of folks from grower families who, in addition to making classical-method bubbles since 2005 (once cavas, now corpinnats) also make a whole rainbow of other wines, both together and separately.

So, like, Toni Carbó regeneratively farms his family vines and bottle hazy, zero-zero fragile gems under the name ‘La Salada’; Ramon Jané makes pét-nat and wild still wines from his families’ vines under the name … Ramon Jané; and Ana Serra, who has since left the project, just released her own bottling of (delicious) xarello pet-nat last year.

The winery itself was built in a village on the edge of the Garraf Massif national park, where Mercè Cuscó, Ramon’s wife and the last member of Mas Candí, has family vines herself. “QX” stands for ‘quatre xarellos’: a mix of old plots (once it was four old vineyards) fermented and aged in four different types of vessel: chestnut, acacia, French oak, and amphora. When they started the winery project, it was one of the first still xarellos they made together, as an experiment to see what xarello could do.

Xarello is naturally structured, high in acidity, with an herbal-mineral dimension that growers making ambitious still wines in cava country have seized on, and it’s definitely the favorite child of the region’s native varieties.

(As for the rest of the family? Sumoll is the black sheep. Macabeo is a hufflepuff-coded middle child. Parellada is a head-in-the-clouds nose-in-a-book type, a little bit of a space cadet. Malvasia de Sítges is the cool aunt. Pansa blanca is xarello’s AIM user name. Cartoixa vermell is a mid-aughts emo-punk kid secretly on honor roll. )

Joan Rubio, xarello, “Essencial”

For fifteen years, Joan was the winemaker at Recaredo, and the guy that introduced biodynamics to the estate. Nine years ago he decided to start his own thing, going back to the family farm (vines, wheat, olive trees) in the center of Penedès and making his own wines (without bubbles).

Notably, Joan doesn’t own a press. Everything is piled into tank and macerated on the skins for varying lengths of time; the weight of the grapes gently squeezes out juice. After a little bit (six days, for this wine) he bleeds off the juice and puts it into a container (big 500L used oak cask, for this one) to age, so there’s a degree of texture here from the skins but almost no press extraction — the shape and structure of the wine is really distinct, deep and fresh at the same time.

He made about 580 cases of this. (To give you a sense of the relative scale at play.)

Ramon Jané, rosé pet-nat, “Tinc Set”

Ramon started his personal project eight years into Mas Candí, as a way to experiment with zero sulfur vinification and color a bit outside of the lines. “Tinc Set” is a pet-nat—made fizzy via a lofi method where you bottle just before fermentation completes—and bottled with zero filtration or added SO2.

The blend is xarello, macabeo, and parellada — our three cava grapes — with the exceedingly rare mando, a late-ripening, drought-resistant Catalan red variety that is almost extinct today, but very resilient against the chaos of climate change.

(Beyond getting hotter and drier in general, Catalunya has endured drought for the last four years. Not only were grape yields last vintage half of what they would be in normal years, vines are dying from heat stress. Freixenet produced a declassified sparkling wine using grapes from outside of the region and furloughed 80% of its workforce for the month of May, and 6 million people have been living with limits on their personal water consumption.)

Penedès’ vines were once almost entirely red varieties, before the mass extinction of phylloxera. It was that replanting — at the very same time that champagne technology was being introduced in Sant Sadurni d’Anoia — that rewrote its viticultural landscape entirely.

Clos Lentiscus, blanc de blancs brut nature, “Greco di Subur”

On the other side of the Garraf massif, surrounded by Mediterranean forest and approaching the sea, Manel Arinyo has spent the last 23 years recovering his family vines. He started the work after years making the wines for Nadal (now a Corpinnat producer), farms without chemicals, plants, prunes, harvests, and bottles according to the moon cycle, and stopped using sulfur in vinification after his wife was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

This is an idiosyncratic wine in a couple of ways. One, it’s made from an ancient, nearly extinct white grape, malvasia de Sítges.

(Malvasias and muscats go back thousands of years in the ancient Mediterranean and trace the trading routes that linked the world sea. They were prized for their aromatics and ability to ripen to high levels of sugar, often dried on straw mats to survive the sea voyage, and often named for the ports they set sail from — like Sítges. Malvasia de Sítges turns out to be synonymous with malvasias in northwestern Sardinia, on the Lipari archipelago north of Sicily, on the Dalmatian coast in Croatia, which just about traces the routes of 13th century Catalán merchant ships. Malvasias tend to be aromatic, but not as wildly perfumed along the orange blossom/honey/jasmine spectrum as muscats are—and also tend to be a bit more rich and textural.)

Two (yes! we’re still just on two), it’s champagne-method, but in an avant-garde vein that has echoes in the ambitious work of natural-leaning grower champagne producers like, say, Flavien Nowack: instead of using cultured yeast in a liqeur de tirage to start the second fermentation, Manel adds frozen grape must from the harvest to begin an indigenous second ferment.

In addition to being single vintage and single (rare) variety and aged about 3 years on the lees, it’s also riddled and disgorged by hand and bottled without added SO2 or dosage.

Buying this level of geeky specificity and handwork in A.O.C. grower Champagne will set you back $80 to $90 in a wine store. Here, it’s between one-third and half of that!

Finca Parera, clarete, “Fins als Kullons”

This is as close as we got to honoring the red winegrowing history of Penedès. (In my defense, it was a hot, humid late spring NYC day when we tasted, and sometimes the narrative has to bend to what is the most fun thing to drink.)

Clarete is a locally traditional, easy-drinking co-ferment of red and white varieties, somewhere between a light red, a dark rosé, an orange wine wearing a pink hat.

In this case, it’s equal parts xarello, garnatxa blanca, and sumoll (white, white, red — or gold, gold, purple, really). The xarello and garnatxa blanc are destemmed into concrete and infuse on the skins at cellar temperature. When late-ripening sumoll joins the party, the juice from the whites is bled off to join the red on the skins.

After fermentation, the wine spends the winter settling clear in concrete tanks and gets bottled in liters without added SO2 in the spring.

Rubèn Parera is, like Manel and Ramon and Joan and Toni and Mercè above, a child of farmers who grew not just grapes, but olives and almonds, wheat and vegetables. He went to oenology school and worked for conventional wineries before returning home to start a project of his own with his farmer father. In the process, he unlearned a lot of what he’d been taught, and by 2015 he was working in an entirely different way.

For the last hundred and twenty years, the region’s fate has been for those farmers to sell the grape they grow to large concerns that turn it into sparkling wine that could come from anywhere.

Even in the face of drought, that business is booming. (That’s why Freixenet had to make declassified sparkling wine that sourced grapes from outside the region, creating a cava even more decoupled from regional reality than usual.)

Meanwhile, the children of those farmers are bottling and selling their own wines. They’re changing the farming— apart from our first bottle of Freixenet, every other producer here is working with organics as a floor, not a ceiling, incorporating regenerative practices, permaculture, and biodynamic sprays.

They’re exploring still versions of grapes that usually disappear into sparkling, like xarello, and varieties that are almost extinct, like malvasia de Sítges, and wine styles that are premodern but feel shockingly contemporary, like clarete.

And for the first time in a long time, we’re discovering in our glasses what Penedès can taste like.

4 thoughts on “Fringe Spain: CAVA COUNTRY”