Muscat!

A two thousand year-old name (Persian muchk, Greek moskos) for an animal we still call musk deer, and for the fragrance derived from the male musk deer gland, and by extension the generic word, in the ancient world, for perfume.

‘Muscat’ never named one grape variety; grapes were called muscats because of their aura, because of the uses to which they could be put, because when you crushed them their scent rose into the air like a physical thing.

Muscats, like malvasias, are a sprawling family put to work across the Mediterranean world. They could yield, and they were resilient: give you thick, heavy bunches as long as your forearm, survive a season without rain, ripen sweet and heavy. You could eat them out of hand at the table, or plant them at the end of rows for pickers to snack on; you could dry them on straw mats and ferment them into strong, honeyed wines that would survive a sea voyage.

Muscats were oared to rocky volcanic spars in the Aegean and accompanied Levantine traders to the western gates of the Mediterranean. They landed in the Adriatic and spread through the old borders of the Hapsburg Empire. They crossed the Atlantic from the Canaries and landed, alongside pais, in the birthplace of viticulture in the Americas.

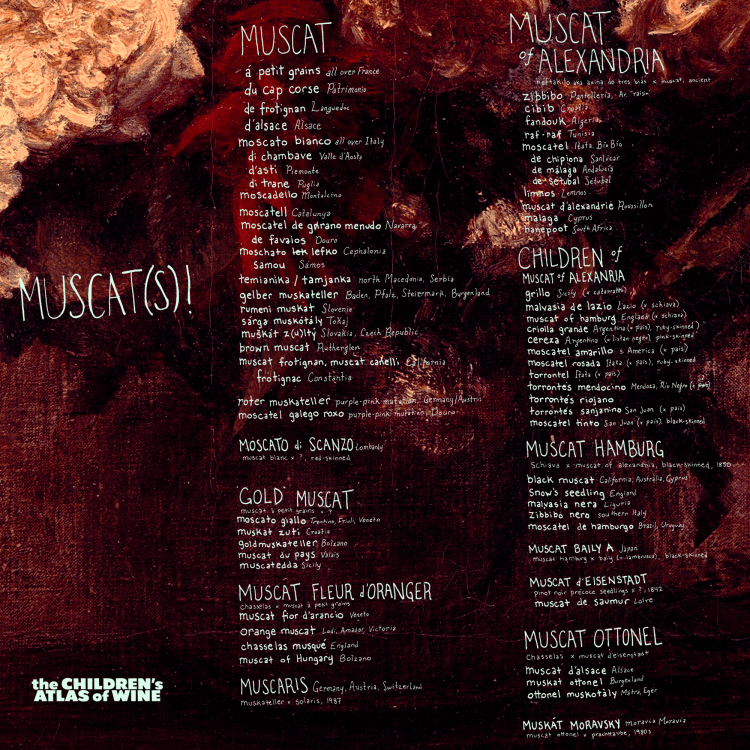

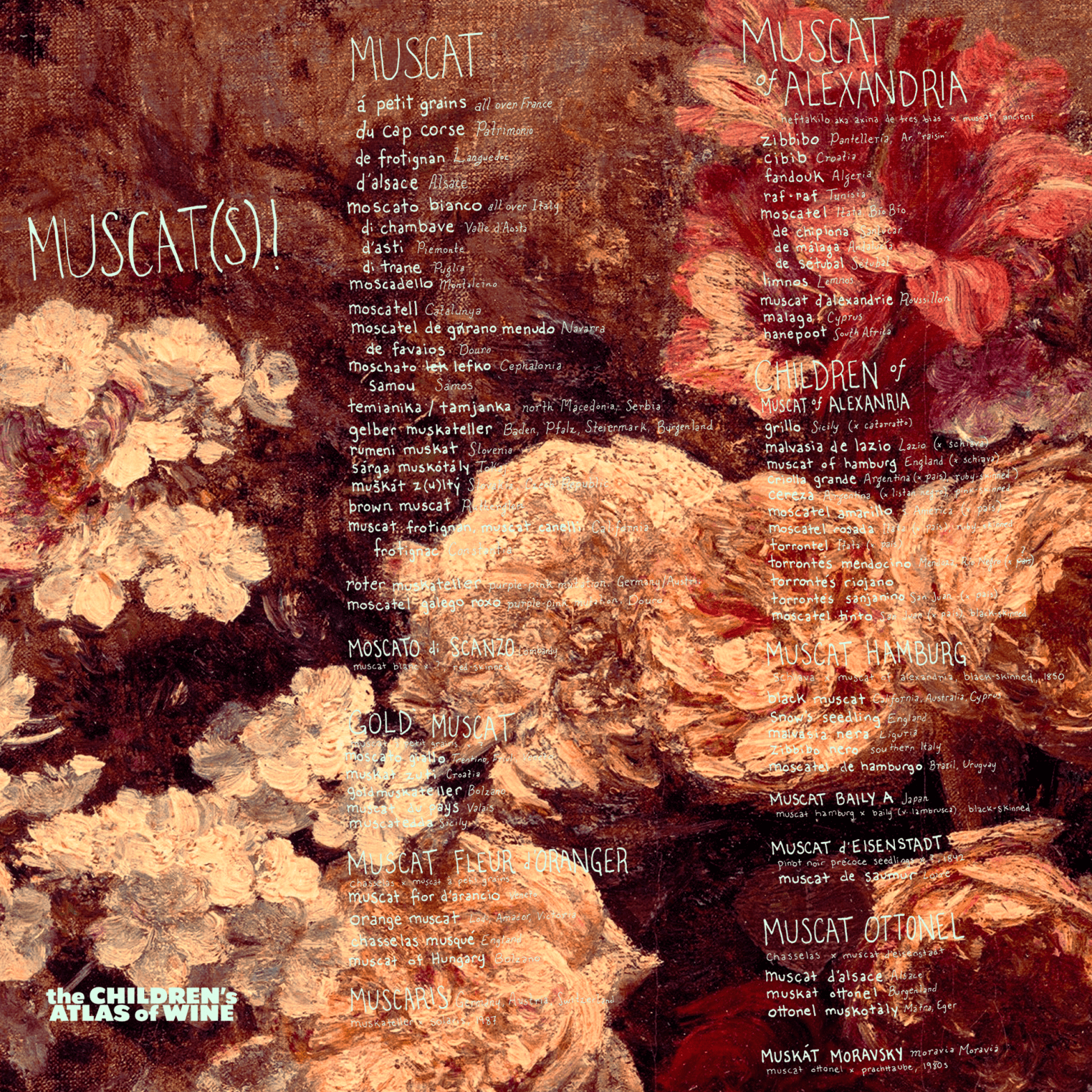

Any muscat variety trails dozens of local names in its wake, like Greek gods with a different statue and aspect in every polis and sacred grove.

They were named for the cities they were traded out of and the islands they departed: Lemnos and Samos, Málaga and Alexandria, Sétubal and Frotignan. They were named for the use to which they were put: in Sicily, the local name for muscat of Alexandria, zibbibo, comes from the Arabic for ‘raisin’; in Algeria, one of its names was fandouk, ‘trading post’.

They were named, in their promiscuous spread, for the many mutations and little localized adaptations they accumulated, color in particular: roxo or roter or tinto or rosado, gelber or sárga or rumeni or yellow, golden or zuti or zltý, brown or black.

The most ancient varieties, muscat à petit grains and muscat of alexandria, have the longest trailing cloaks of mutation and synonym, like peacock feathers. They have children in the wild, and children that were bred.

Muscat of alexandria—moscatel from Spain across to the Americas, called malaga in Cyprus and hanepoot in South Africa and cibib in Croatia (loaned from the Arabic)—is particularly resilient long-lived. Its oldest vines are a hundred years of age, two hundred, three. In Peru and Chile and Argentina and Baja California it crossed in the wild with pais and made a sprawling family, criolla grande and moscatel amarillo and torrontel and torrontés sanjanino and torrontés mendocino and torrontés riojano and many more without names.

Smelling, as they do, of orange blossoms, or jasmine, or honeysuckle, or daffodils from the flower to the green sap of the stem, all muscats have an enduring association with sweetness. They’re testaments to the priorities and desires of people who lived and died a long, long time ago: what smelled nice, what was prestigious, what would keep.

And for thousands of years, the muscat in your glass from a faraway place probably would have been sweet, too. They’d get dried on straw mats to concentrate the sugars in Pantelleria or Málaga; oxidized and fortified into brown-gold, syrupy nectars in Rivesaltes and Rutherglen; and, fatefully, turned into a lightly sweet, lightly sparkling specialty of a small part of northern Italy that has become a global beverage brand.

(Did you think we could talk about muscat without talking about moscato d’Asti?)

Sweetness, at least in northern Europe, had a certain cultural currency: rare, prized, associated with popes and aristocrats. Kings used to commission sugar icons of their enemies’ fortresses and heraldry and consume them at the victory feast. Sweetness—the fleeting bloom of a ripe plum, the taste of honey, the flavor of a late-harvest wine–was a rare dream, in the cold north. You paid, or if you could not pay, you waited, for the fleeting glimpse of a sweet thing.

Colonialism changed all of this. Suddenly, sugar meant the treacle on white bread and the cubes fortifying weak, milky tea for workers on the way to the factory floor. Suddenly, treacle was a synonym for insipid, common, sentimental.

Sweetness, available everywhere and to everyone, just wasn’t special anymore. (‘Everywhere’ means ‘in the capitals of colonial empires’; ‘everyone’ means, ‘those imperial citizens’, stirring sugar into their imported coffee and tea, sweetening their imported chocolate. The benchmark anthropological text here, which I’m glossing, is Sydney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History.)

Sweetness, once rare, became commonplace — and, commonplace, became something to adjure, deny, proof of your low origins and your lack of discrimination. Postwar technology—cold stabilization, sterile filtration, must rectification—made it trivial to dial sweetness in and up, taking what was contingent and complicated in the vineyard, the village waking up on Christmas morning to pick the eiswein, and turning it into something you could set to the milligram.

Moscato — an unrelated galaxy of ancient, prized grape varieties — wasn’t the only thing flattened into a caricature of itself when it was turned into a global beverage brand, but it’s arguably had the worst of it.

Regular folks might still think that riesling is sweet, but at least they know it’s a grape— and one with sommeliers lined up to defend it and sing praises to its nobility, namecheck German abbeys, etc.

Where are muscat’s defenders?

Muscat, in all of its spectrum, became synonymous with one wine style made in one place: moscato bianco (muscat à petit grains) in Asti, slightly sweet and sparkling and first commercialized in the mid-1970s. Asti’s not tiny like Chambertin, but it’s not infinite, either: a little less than 10,000 hectares of moscato vines, some of them on old, steep slopes, producing around 85 million bottles per year of sparkling wine. [*]

Today, with beverages like Skinny Girl and Myx (made at Pleasant Valley Wine in New York in a line that includes sangria, coconut, mango, and watermelon flavored variants — who knows where the grapes are from? the internet tells me, “imported”), moscato feels like a lifestyle brand, not a grape variety. It’s demographically marketed and segmented. Drinkers describe themselves as outgrowing it, leveling up from it, apologize for ordering it.

Human beings, also, like sweet things. They like honey, and flowers, and a peach falling apart in their hands, and watermelon dripping down their chin, and ripe mango, and walking in the garden. To the extent that an entire European aesthetic universe from Kant onward has been about good taste and discrimination abjuring the body in favor of the disinterest of the judging eye, there’s something perverse in what we’ve trained ourselves to do, here — in the idea that dry is sophisticated, and that what makes you feel good is suspect.

But it’s also true that muscats out here in the world are largely only sweet because of an industrial set of winemaking tools, tweaked and polished and stripped to within an inch of their lives, as far away from the reality of water and sunlight and soil as you could get. And it’s true that the grapes that will be fed into those factories become more and more interchangeable commodity melting into air. The places they’re grown are still real — they’re just being made worse in being made invisible.

Natural wine — as an aesthetic category and as an ethos and as a community of makers and drinkers — opens a door in the side of the mountain. Sweetness in natural winemaking and uncontrolled fermentation is as rare and precious as it was five hundred years ago. Wines with skin contact, with their full spectrum of texture and body intact, with the wildness and dimension of natural fermentation, lean into the lush perfume and diversity of muscats without erasing who they are or where they came from.

It’s just weird enough, maybe, to be a way out of the bind: green, delicate, springy gelber muskatellers in the garden gorges of the Steiermark; crushed orange blossom zibbibo in Sicily; salty-savory sourdough and green mango moscatel under flor in Cadíz; lavender and lemon balm moscatel with skin contact in Itata; smoke and sea spray and honey moschato in Sámos…

Here’s a list of we’ve tasted in class over the years (unless I forgot to add something), fortified with a few bottles drunk with friends so that it’s the most complete list possible:

MUSCATS GREEN + GOLD

GARALIS, muscat of Alexandria + splash of limnio ‘Rozsa’ LEMNOS skin contact

SOUS LE VÉGETAL, muscat of Alexandria ‘Livia’ SAMOS

ARIANNA OCCHIPINTI, albanello & zibbibo “SP-68” VITTORIA

RAUL MORENO, moscatel, “La Pretension” SANLÚCAR DE BARRA skin contact, under flor

MUCHADA LÉCLEPART, moscatel de chipiona & palomino “Elixir” SANLÚCAR DE BARRAMEDA

MINGACO, moscatel “Fermentación Pipeña” ITATA skin contact

LEONARDO ERAZO, moscatel “La Ruptura” ITATA

GUSTAVO MARTÍNEZ, moscatel, “Kilako” ITATA skin contact

VIÑATEROS BRAVOS, moscatel, corinto “Pipeño Blanco” ITATA skin contact 1-liter

ROBERTO HENRÍQUEZ, moscatel, corinto, sémillon “Rivera del Notro” BÍO BÍO skin contact

ROBERTO HENRÍQUEZ, torrontel (pais x moscatel) “Super Estrella” BÍO BÍO skin contact

TERAH BAJJALIEH 105 year-old orange (?) muscat LIME KILN VALLEY skin contact

MEGAN BELL [MARGINS], muscat blanc [à petit grains] CONTRA COSTA COUNTY

FACE B, muscat petits grains, “Yoshi” ROUSSILLON

MATASSA, muscat d’alexandrie, “Cuvée Marguerite” ROUSSILLON skin contact

PETIT DOMAINE de GIMIOS, muscat petit grains, “Muscat Sec” SAINT JEAN DE MINERVOIS

JOSEF TOTTER, muskateller-based hybrid, ‘Muscaris’ STEIERMARK

SEPP MUSTER gelber muskateller ‘Vom Opok’ STEIERMARK 2018

WENZEL, gelber muskateller ‘Wild & Free’ BURGENLAND skin contact

LAURENT BANNWARTH, muscat ottonel & a little bit of muscat petit grains

LAURENT BARTH, muscat à petit grains & 5% muscat ottonel ‘Muscat d’Alsace’ ALSACE some residual sugar

ERIC TEXIER, field blend including muscat à petit grains, chasselas, & pinot gris ‘Calico’ BEAUJOLAIS

MUSCATS PINK + PURPLE + BLACK

ROBERTO HENRÍQUEZ, moscatel rosado, ‘Super Estrella Rosado’ BÍO BÍO skin contact

CARA SUR, moscatel tinto ‘Moscatel Tinto’ CALINGASTA

2 thoughts on “Grape Files: Muscat(s)!”