Up mule paths and mountain streams west of Madrid grows a treasurehouse of old-vine garnacha that tastes like nowhere else.

Strikingly transparent in the glass, silky + swooning + lifted despite what can be formidable tannic structure and powerful, naturally ripe alcohols, they’re what wine writers will often call ‘delicate’ and ‘Burgundian’—which, as I’ve written, may just be a way of saying that they’re ‘very good’ within the bounds of our current aesthetic paradigm.

At any rate, they are good, and radically distinct from the purple soup from places like Navarra and Aragón that I was used to running into when I was a baby somm, the wines that made me wince and say, well, I guess this is what they mean by ‘varietal typicity’. Blech.

The first time I tasted a garnacha that turned out to be from Gredos, it must have been around 2015 or so. I didn’t know that Gredos was where it was from — I just knew that, suddenly, I was in love with a grape I thought I didn’t like, and that it was doing things I didn’t know grenache could do. Imagine my surprise—my delight!—at my precious little certainties being blasted into smithereens.

It turns out that I was in love with a place—I just didn’t know it yet.

This is the story of that place, and about why it took me so long to realize that it was a place:

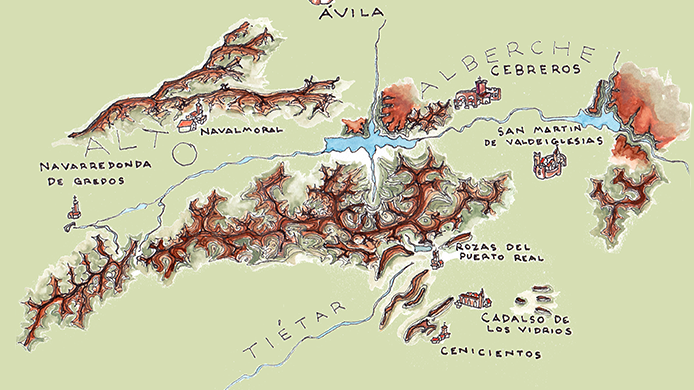

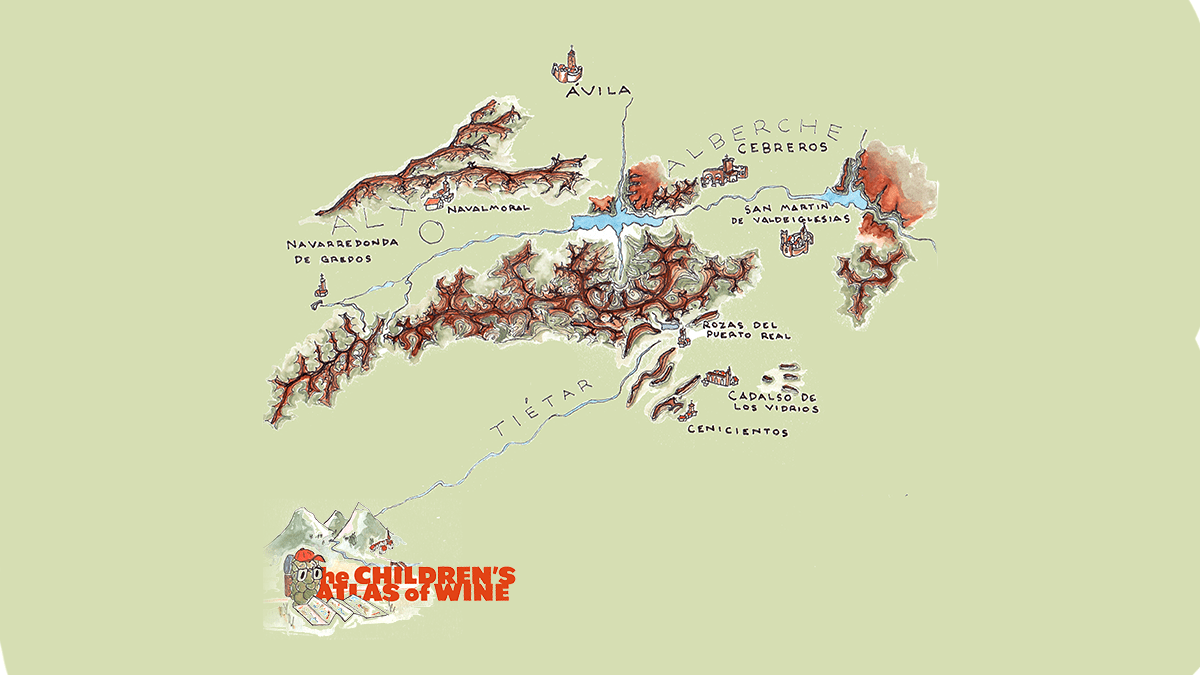

Reason one is purely structural. The Gredos mountain range (it’s also a national park) is definitely a thing—a natural feature, a landscape—but in terms of internal Spanish administrative boundaries it’s politically split between the borders of three regional autonomías: Madrid, Castilla y León, and Castilla la Mancha.

This has meant that the appellation on the label of bottles from here is also all over the place, depending on who’s in charge, and that it will never be just ‘Gredos’ (despite some folks, illegally, writing it anyways). Your bottle might read Vinos de Madrid, or D.O. Cebreros, or VdT Castilla y León, or Méntrida.

Reason two is history (and money): until recently, nobody was in a position to care too much about those distinctions, or about undoing that confusion.

For most of the 80s and 90s, the region itself was sleeping. It was dominated by decaying rural cooperatives who had built a wine economy on backbreaking handwork of old bush vines on slopes too steep to ever mechanize. (The only way you make bulk wine out of a situation this obstinate is rural poverty. Enter postwar Franco-era Spain!)

Those cooperatives hadn’t been a going business model for a long time — there were other places you could get bulk wine, places flatter and easier to mechanize, and after Franco’s death and Spain’s reintegration into Europe that bulk wine could come from just about anywhere. In the race to the bottom, Gredos got out-competed.

Still, the vines never went away. The old pensioners who had owned those plots and sold the fruit to the co-ops weren’t necessarily working them anymore, but they weren’t going to tear them out. And what was anybody going to do with that land anyway? Many of the plots don’t even have road access—take a look (courtesy of the website of importer José Pastor) at how 4 Monos transports their garnacha from the vines down to the cellar at harvest:

By the aughts, a growing community of producers had begun to recognize and celebrate what had been here all along. By 2015, wines were crossing the ocean, percolating through the famously jaded and spoiled NYC wine market, and ending up in the glass of this baby wine person.

Here’s a quick timeline, featuring only the folks I started to seek out and drink, organized by the year of their first vintage:

1999 — Ruben Díaz, son of Gredos, has an awakening when some of his family’s vines were at risk of being pulled out. Ruben is one of those mentor figures many regions have, maybe better known inside by other growers than outside, in the clout-chasing wider world.

2008 — Comando G, the one the British now spend $$$$ on and compare to Rayas—not that the wines aren’t great, but so are all of the other wines in this list, and isn’t it just that wine people love to elevate one producer in an emerging region out of their context, pretend they’re singular geniuses untied to community?

2006 — Going backwards for a second: Bernabeleva’s first vintage, and also the winery where Daniel Jimenez Landi and Fernando García made their first wines for Comando G. (But current release of Comando G’s top wine goes for almost $1,000, and you can still buy Bernabeleva for around $20 retail.)

2010 — Daniel Ramos moves to an old co-op in El Tiemblo; 4 Monos (a team of four ‘monkeys’ including Javier Garcia, former head winemaker at Daniel Jimenez Landi’s family bodega in Méntrida) makes their first vintage in Cadalso de los Vidrios.

2012 — Orly Lumbreras with his neighbor Alfredo Maestro, up north in Alto Alberche. (Orly also collaborates with Ruben Díaz).

Time matters, and so does money, when it comes to the places we decide to treat as regions. But like a lot of places that are actually regions, whether or not we opt to treat them as such, there is a feeling here — a community of growers, a shared history, a unity across style and diversity of site, geology and weather, a feeling both in the landscape and in the wines themselves, in your glass— that shines through.

And practically speaking, engaging with the Gredos as a place unlocks an expanding universe of new growers and wines to discover, if you’re curious enough to use the region as a key. (Even if it’s as simple as, ‘I want grenache that tastes like this, not like that.)

GIVING CREDIT

Discover is a bad verb, and I think there’s a tendency in writing reference material to fall backwards into a kind of omnipotent writing voice of abstract authority, as though this dropped out of the sky. I wasn’t discovering anything when I tasted a garnacha that surprised me ten years ago. All I could do, having been surprised, is look around to see if I find some context, and some people who knew more than I did.

Most importantly: Ariana Rolich, former Spain buyer for Chambers Street and now an importer, opened my eyes to this place and helped me understand what I was looking at. Her old Chambers offers are still great windows onto the growers who she would go on to represent in the market, and she likes grenache a lot more than I did.

It’s also worth mentioning Luis Guttiérez, once at JancisRobinson.com and now at the Wine Advocate, who has been covering this beat attentively for over a decade.

And the growers themselves, of course, know what they have and where they are.

These days, it seems like the concept of Gredos is finally percolating into the wider community of people who taste and sell wine for a living — you’re even seeing it as a category in wine lists from time to time! Someday, probably sooner than I think, this atlas entry will be a quaint time capsule.

EXCEPTIONS

Grenache / garnacha is the headline here, but a wine region is never that simple.

Conquista This was the birthplace of listan prieto (pais), before it was taken to the Canaries and from there in the holds of ships to populate the west coast of the Americas. It disappeared here a long time ago, but I hear at least one grower has planted a new plot to bring it home.

White wine, i 90-plus percent of the time in Gredos we’re dealing with red wine, but there are whites, too: mostly you’ll see albillo (confusingly, there are two albillos, real and the much rarer mayor) which can be floral and tends towards this glycerol-y texture that I personally find really compelling when there’s a bit of skin contact.

White wine, ii There’s also a little bit of chasselas that came over from Alpine Europe on the Camino de Santiago (and, from there, to Itata and Bío Bío, where it’s called corinto). Also a white grape of neutral minimalism that likes a little texture.

LIKE A WINE LIST

Here’s a list of wines from Gredos that we’ve tasted in previous classes, events, and wine kits. (This does not include the Gredos wines I’ve drunk or put on lists!)

See if you can find the villages below on the map:

GREDOS, GARNACHA

4 MONOS, three village parcels “GR-10” SAN MARTÍN DE VALDEIGLESIAS, CALDALSO DE LOS VIDRIOS, CENICIENTOS

4 MONOS, tiny amounts of garnacha blanca + cariñena “Cien Lanzas” CENICIENTOS

BERNEBELEVA, “Navaherreros” SAN MARTÍN DE VALDEIGLESIAS

RUBEN DÍAZ, five high-elevation vineyards “Paso de Cebra” CEBREROS

RUBEN DÍAZ, single parcel “La Escalera” CEBREROS 2019

DANIEL RAMOS, single parcel “El Altar” CEBREROS 2018

ORLY LUMBRERAS, in a tinaja buried in its own vineyard “Malandro” NAVARENDONDA 2016

GREDOS, NOT GARNACHA

RUBEN DÍAZ, chasselas ‘Doré’ CEBREROS skin contact