A class held at Tin Parlour, a new conservas wine bar in the back of Nudibranch, in the East Village, on Tuesday, January 30th 2024. Our next class at Tin Parlour is on Tuesday, February 27th.

Our first in-person class of the new year, ‘Fringe Spain’ was a tinned fish and porrón-fueled exploration of the places where the idea of ‘Spanish wine’ unravels, from the gallego-speaking fjords of the Atlantic coast to the river valleys of the catalan Mediterranean.

There’s always more to learn and think about when you’re tasting, whether you’re a curious drinker or an aspiring professional. Below, here are more details on what we drank, where it came from, and where to look if you’d like to dig deeper:

Here’s how this lineup might look on a wine list:

NANCLARES, albariño “Tempus Vivendi” RIAS BAIXAS

ALBAMAR, espadeiro “O Esteiro” 2017 RIAS BAIXAS corked 😦

GUÍMARO, mencía RIBEIRA SACRA

FRISACH, carinyena “l’Anit” TERRA ALTA

UROGALLO, albarín “Pésico” 2017 ASTURIAS

COSMIC, macabeu “Via Fora” 2019 PENEDÈS

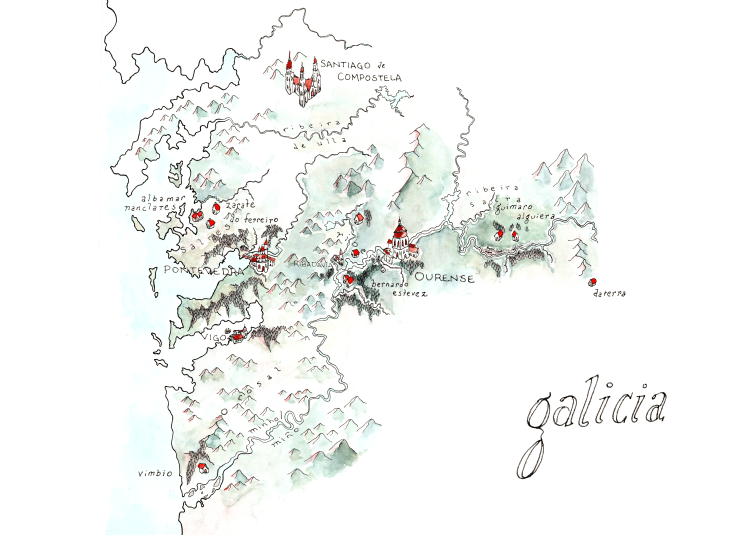

How many people that we tasted can you find on this map?

Questions to ask while you taste

- What do you expect when you picture wine from Spain? In what ways to these wines live up to, or challenge, those expectations?

- We tasted bottles from both the warm, Mediterranean climate of Catalunya and mild, rainy Green Spain (Galicia and Asturias). How did the wines reflect their landscapes? In what ways did growers try to find freshness in warm places, and richness in cooler ones?

- Along with our wine, we tasted country ham draped over Korean rice cakes, tuna belly with red peppers, mussels, garfish, and more. How did the food change your experience with the wines? How did the wines change how you perceived the food?

A little more detail

(Scroll further down for a lot more detail)

NANCLARES Y PRIETO, albariño “Tempus Vivendi” RIAS BAIXAS

Who made it? Alberto Nanclares and Silvia Prieto.

Out of what? Albariño, a high acid wine grape born around the Miño river, after an ’80s planting boom the signature white grape of Rias Baixas.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation, aged on lees in stainless, bottled without filtration or addition apart from a dash of sulfur.

From where? Salnes, in Rías Baixas, around the village of Cambados, albariño’s heart.

ALBAMAR, espadeiro “O Esteiro” 2017 RIAS BAIXAS

Who made it? Xurxo Alba. (The x’s are sh sounds.)

Out of what? Espadeiro, an herbal, crunchy, high-acid red grape that probably came here on pilgrimage from Basque France. Along with caíño and mencía, one of the rare red grapes of Rías Baixas.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation in stainless, aged in neutral oak, bottled without filtration or addition apart from a dash of sulfur.

From where? A seven-minute walk from Nanclares.

GUÍMARO, mencía RIBEIRA SACRA

Who made it? Pedro Rodríguez and team; Guímaro is gallego for ‘rebel’.

Out of what? Mencía, middleweight, plummy, and herbal.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation in stainless, bottled in the spring.

From where? Amandi, in the heart of the green slate terraces of Ribeira Sacra.

FRISACH, carinyena “l’Anit” TERRA ALTA

Who made it? Francesc Ferré and his brother Joan.

Out of what? Carinyena, a variety born in Aragon and spread through the Mediterranean during the 13th-century Catalan golden age.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation, infused in whole cluster, aged in concrete and old oak, bottled without additions.

From where? Corbera d’Ebre, a high valley in the Catalan borderlands of Terra Alta.

UROGALLO, albarín “Pésico” 2017 ASTURIAS

Who made it? Fran Asencio.

Out of what? Albarín (not to be confused with albariño—this is potato-tomahto!).

Made how? Native yeast fermentation, aged on lees in big cask over two winters until it settles clear, bottled without SO2 or filtration.

From where? Cangas, a slate valley with some of the steepest vineyard slopes in Spain, a couple of dozen miles from the sea in Asturias, land of sheep, cider, and cheese.

CÓSMIC, macabeu “Via Fora” 2019 PENEDES

Who made it? Salva Batlle Barrabeig.

Out of what? Macabeu, one of the big three grapes of cava country.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation with five days on the skins before gently being drained off without pressing, aging in a mixture of tank and amphora, bottled without SO2 or filtration.

From where? Penedès, inland of Barcelona, the heart of cava country.

A lot more detail

NANCLARES Y PRIETO, albariño “Tempus Vivendi” RIAS BAIXAS

Who made it? Alberto Nanclares and Silvia Prieto. Alberto started farming and making wine in his garage by the sea in 1997, first conventionally, then slowly but surely eliminating chemicals. A decade later, it was his full-time gig. Silvia was a lab technician from Pontevedra who emphasized traditional approaches to organic farming and winemaking without additions; she met Alberto in 2009, and joined him in 2015 after working a harvest. (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Albariño/alvarinho (potato-potahto), a high-acid white grape born on one side or the other of the Miño (Minho) river—there are still 300+ year-old albariño vines producing wine today (try Do Ferreiro’s “Cepas Vellas”), so it’s been around for at least that long. After a planting boom in the ’80s, it’s now the dominant cultivar in Rias Baixas and the foundation of its commercial identity. (Think going to a grocery store to buy a $16 bottle of Martín Codax, a brand/cooperative founded in 1985 with 300 farmer-members named after a 13th-century Galician troubador.)

Made how? The core of how Alberto and Silvia make their wine, with both fruit they purchase from other farmers (like this bottle, from plots around Sanxexo, a village just to their south) is fermentation and aging on the slurry of spent yeast (lees) in the same vessel without moving things around too much. They’re inveterate tinkerers and keep playing with how they vinify single plots, so you see this general principle used on a whole slew of different containers: steel tank (like this wine), big oak cask, French 225Ls, reconditioned 90 year-old chestnut barrels, amphora. Most local commercial producers routinely deacidify with potassium (and a lot of grocery store albariño, consequently, tastes like orange juice and stale beer). Because Alberto and Silvia don’t, and because pH is so low and acid so high, their wines almost never go through malolactic. Mostly, like Hofgut Falkenstein’s rieslings, they just settle clear on the gross lees until they’re etched like crystal and ready for bottling without filtration.

From where? Salnes, in Rias Baixas, around the village of Cambados, albariño’s heart. Rias are the crinkled-up fjords or estuaries that define Galicia’s Atlantic coast; the rias baixas are the lower rias. Geology tends to be granitic sand. As far as Rias Baixas subzones go, Salnes is home to the highest concentration of folks that get my heart racing, and also tends to be the nerviest / highest acid / closest to the sea. (Compare to down south by the Miño in O Rosal, on the Portuguese border, where albariño is more often blended with other borderland white grapes like loureiro and treixadura, and the wines tend to be richer and a bit more on the soft yellow fruit.)

ALBAMAR, espadeiro “O Esteiro” 2017 RIAS BAIXAS corked 😦

Who made it? Xurxo Alba (great gallego name!), first vintage 2006, from a mix of vines planted by his family in mid-80s (remember that planting boom?) and fruit sourced from smallholding neighbors—the average vineyard holding here is smaller than Gramercy Park. (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Espadeiro, which along with cultivars like caíño tinto and mencía are among the rare (1% of plantings) red grapes of Rías Baixas. Confusingly, this is apparently not the same (according to some recent DNA profiling) as the espadeiro across the river in Portugal—instead, it’s an almost extinct variety from Basque Country/Jurançon/Béarn that’s probably a distant country cousin of tannat and cabernet franc. This wine comes from rare survivor vines over 200 years old, as well as a younger planting.

Made how? Albamar, like Nanclares, is one of the few producers in this difficult-to-farm region who’s no bullshit: native yeast fermentation, no filtrations or additions. In this case, fermentation in steel, pressing into used oak 225Ls, aged for 12 months and bottled. (And then aged under cork for another 6 years, until I opened it this week to realize it was corked.)

From where? In the village of Cambados, a seven minute walk from the Nanclares cellar in Rias Baixas.

GUÍMARO, mencía RIBEIRA SACRA

Who made it? Pedro Rodríguez and team. (Guímaro means ‘rebel’ in Gallego, an allusion to a 15th-century struggle of a local armed peasant brotherhood, the Imrandades, who challenged the local nobility.) Pedro’s family made wine for themselves and sold their wines in 20-liter glass containers to local cantinas; in 1991, they became one of the first growers in the region to start bottling their own wines. (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Mencía, the signature (although not only) grape of Ribeira Sacra, which for me does figure eights between the freshness and elegance of pinot noir, the herbal, peppery character of cab franc, and the meaty smokiness of syrah—depending on producer style, site, and vintage. This is their entry level, from plots around the region. Guímaro is notable in planting and bottling some of the region’s other varieties, from brancellao and merenzao to caíño and sousón.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation in stainless steel, bottle in late spring, easy-peasy. The single site wines are even older school: foot-stomped, whole cluster, in open-topped wood cask.

From where? Around the village of Amandi, in the heart of the plunging slate terraces and dramatic, green landscape of Ribeira Sacra. The terraces date back to the Romans, but Franco-era dams have changed the level of the river and submerged some of the oldest planting sites; you can see them, still, below the water. While Rías Baixas has had an international commercial identity since the ’80s, Ribeira Sacra’s reputation (and the number of growers making wine) was decidedly lower-key until the last decade or so.

FRISACH, carinyena “l’Anit” TERRA ALTA

Who made it? Francesc Ferré, along with his brother Joan who although from a farming family became the first generation to bottle and sell their own wines rather than selling fruit in 2009. The kid’s one of the (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Carinyena, born in Aragon and taken throughout the Mediterranean during the 13th-century rule of James I, when Catalan merchants ruled the waves and walked the streets of Tunis and Catalan mercenaries fought for emirates on the Aegean sea and sacked Athens, and carinyena (carignan, cariñena) ended up in Sardignia and Mallorca and the Roussillon and even further. High acid, high-color, high tannin, it’s drought resistant and can yield heavy and tends to have been put to work in the places it’s been taken, which gives it something of a reputation. (Jancis Robinson calls it a “cussed brute” with a “host of disadvantages”.) I might say, instead, that its ability to survive as regions get hotter and hotter and hold on to freshness is an important virtue in the Anthropocene—and that, when treated with intention and care, it is instead capable of grace.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation on whole clusters, infused without much in the way of extraction for one month, decanted or pressed off (it’s hard to tell, but it must have been gentle, it’s so light) to age in 225L old barrels and concrete tank. Bottled without filtration or SO2 addition. (“Anit” means “evening.”)

From where? The oldest carinyena vines Francesc farms, planted sometime just before or just after the Civil War, in the high valley of Corbera d’Ebre in Terra Alta, on the Catalan borderland, scarred by the last battles of the nationalist march on Barcelona. (It fell to the fascists four days and 85 years before our class, on January 26th, 1939.) Francesc is one of the very few independent bottlers in the region; most farmers sell to the local cooperative winery.

UROGALLO, albarín “Pésico” 2017 ASTURIAS

Who made it? Fran Asencio, who after working in renewable energy abandoned everything in 2011 to dedicate himself full-time to viticulture. He farms 17 hectares in Asturias, as well as having purchased and rehabilitated an old sherry bodega on the opposite side of Spain. (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Albarín, a rare grape native to Asturias that may be a child of savagnin—from what I’ve tried to parse of the scientific literature, it’s a little unclear whether there was a mislabeled sample vine or whether, following that, it turned out that there actually are 20 or so points of contact. Trousseau, another grape of the Jura, traveled all the way out to Galica (and from there to Madeira, Porto, and even further) via the Camino de Santiago, so it’s not impossible that savagnin did too—and had a kid along the way. “Pésico” is the name of a pre-Roman indigenous people who lived in the valley Fran farms two millennia ago, and the name of the bottling from Fran’s oldest vines, on some of the steepest slopes in the world, a couple of dozen miles from the sea.

Made how? Native yeast fermentation and aging in the same large cask (like Nanclares!) on the gross lees over two winters, until it settles clear. Bottled without filtration or any additions including SO2.

From where? The Cangas de Narcea, in Asturias, a sparsely populated country better known for cheese, sheep, and cider—but with a history of winegrowing that goes back generations. When powdery mildew arrived in the mid-1800s, viticulture in this rainy, temperature region began to collapse; phylloxera sealed the deal. Today, the Cangas valley (which is searching for DO status) has eight working wineries and just 55 hectares of vines.

COSMIC, macabeu “Via Fora” 2019 PENEDÈS

Who made it? Salva Batlle Barrabeig, who started making wine from his family’s vines in lower Penedès while simultaneously moving to Empordà, just on the border with French Roussillon, to start his own project. This was ten years ago or so—he’s also a big fan of amphora and carinyena blanc. (Read more at the importer website.)

Out of what? Macabeu, one of the ‘big three’ grapes of cava (along with rarely-seen-alone parellada and king xarello). Macabeo/macabeu/viura is widely grown in Spain, and also a lowkey supporting player across the border in the Roussillon, although what it’s like, exactly, is probably not super clear even to very experienced tasters. Softer than xarello, certainly? A little thicker than parellada? This bottling is from a single named vineyard planted in 1956 in the heart of cava country.

Made how? Macerated on skins and some stems for 5 days, drained without pressing (infusion!), fermentation in tank, aging in a mixture of tank and amphora. Bottled without filtration and with zero added SO2.

From where? Penedès, the limestone river valleys over the coastal range from Barcelona (but before the second mountain range)—a region once planted to mostly red grapes until phylloxera and, shortly thereafter, the invention of cava, once called xampán. Today, cava is big business: three companies control over three-quarters of production, including the largest producer of sparkling wine on the planet. (Drizly will deliver you a bottle of $12 Freixenet black label in under an hour, google tells me.) The revolution, in Penedès, has been the children of these grapegrowers starting to farm without chemicals and bottle their fruit themselves, maybe for the first time in their family’s history, instead of selling to the cava factories—and all of this has happened in the last one to two decades.

One thought on “‘Fringe Spain’ @ Tin Parlour”