Lineup notes and recaps for classes hosted in 2026. Updated periodically!

fermentation is magic @ liz’s book bar, 3/6 [tickets]

all things pinot @ vine wine, 2/23 [tickets]

industry blind tasting @ vine wine, 2/23 [tickets]

industry blind tasting, 2/16

champagne, pet-nat, sparkling, 2/9

industry blind tasting, 2/9

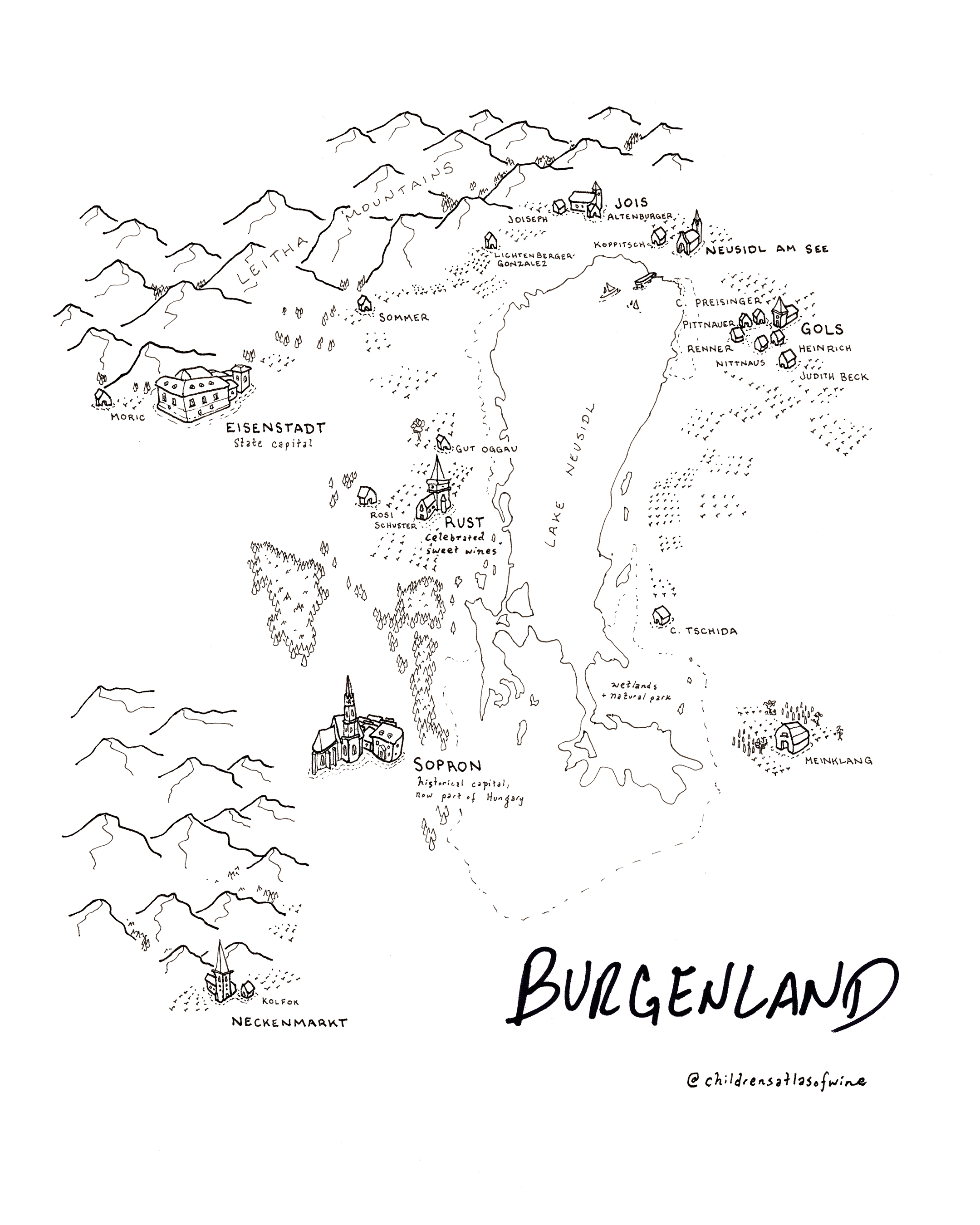

burgenland, 2/8

industry blind tasting, 2/2

wine 101, 2/2

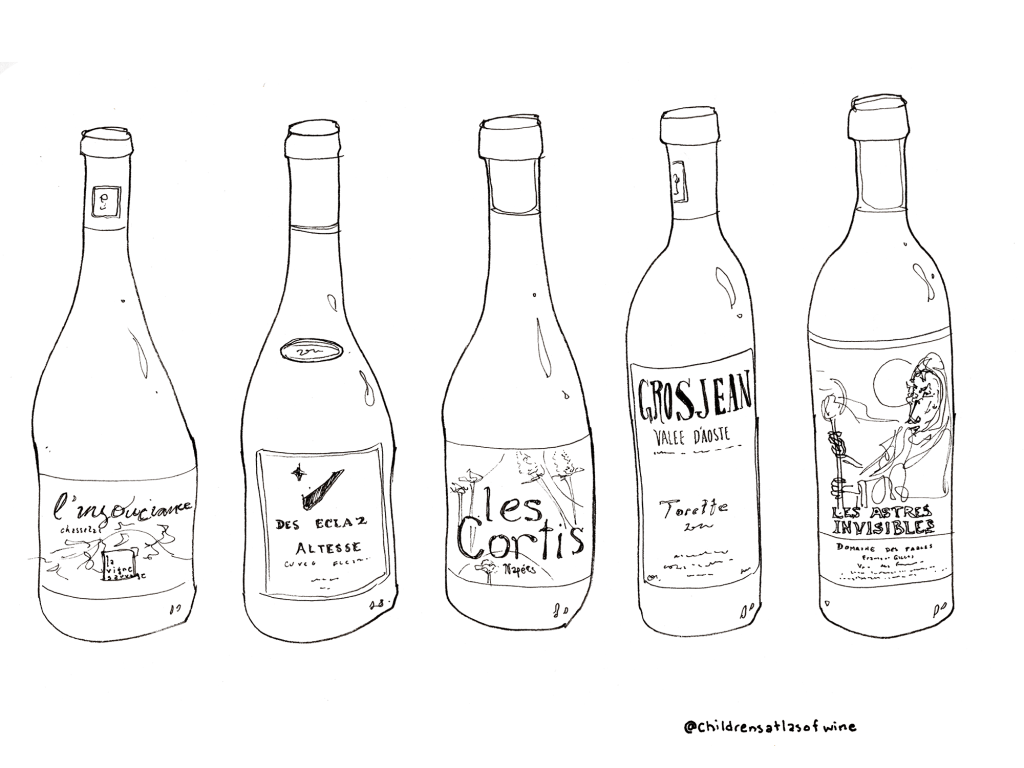

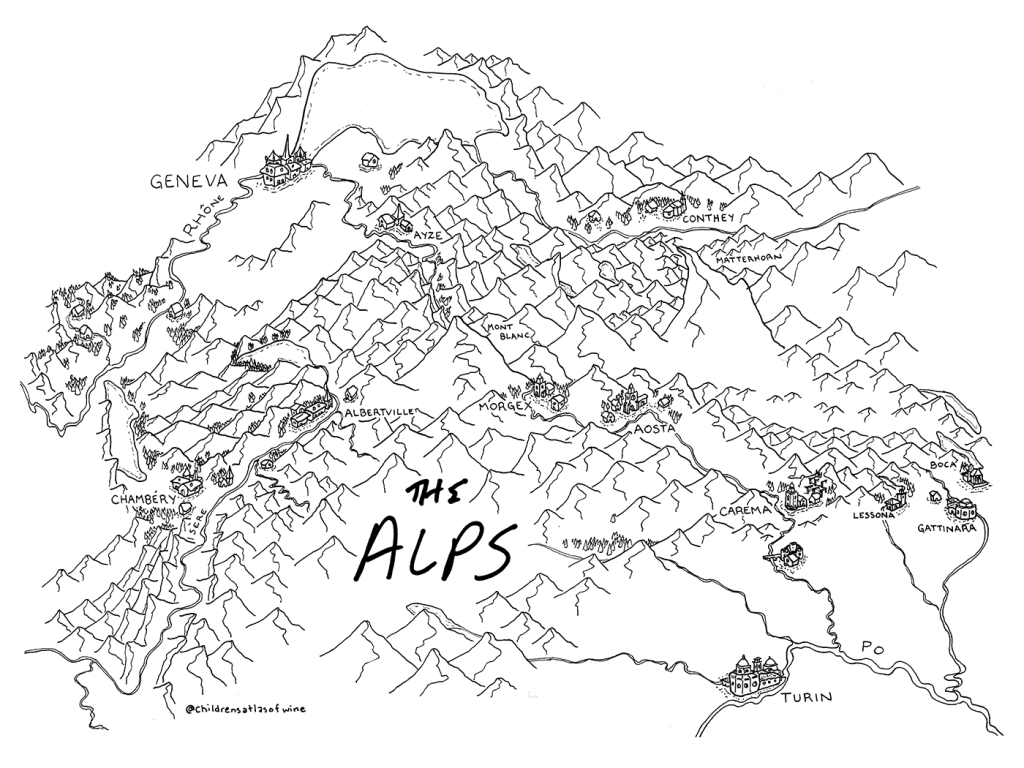

alpine wines, 1/21

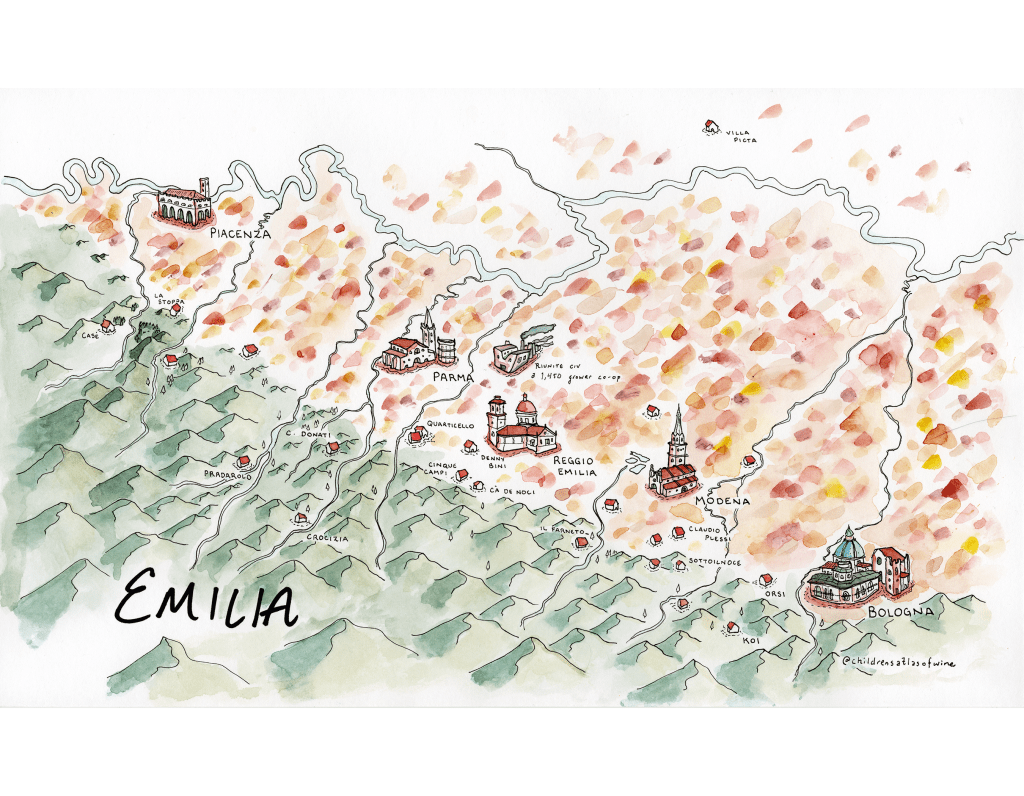

emilia romagna, 1/18

2/9 @ vine wine — sparkling!

CHAMPAGNE, PET NAT, and MORE

Crémant de Jura, champagne-method chardonnay

Sparkling Vouvray, champagne-method chenin

Montlouis Pét-Nat, chenin across the river

Orange Pét-Nat, skin contact rebula + chardonnay in Slovenia

Grower Champagne 1 solera blanc de blancs in the Montagne de Reims

Grower Champagne 2 co-planted pinot and chardo in the Montagne de Reims

2/9 @ vine wine — industry blind tasting

we tasted backwards, started with the final two wines and ending with the whites at A & B:

E. Bloomer Creek, ‘Vin d’Ete’ cabernet franc Finger Lakes

F. Villeneuve, Saumur-Champigny cabernet franc Loire

C. Kewin Descombes, ‘Keke’ gamay Beaujolais

D. Laurent Lebled, ‘Ça C’est Bon!’ gamay Cheverny

bonus (not pictured) Villemade, ‘Bovin’ gamay Cheverny liter

A. Leo Steen, chenin, Dry Creek Valley

B. Sérol, ‘Pourquoi Faire Sans Blanc?’ chenin, Loire Volcanique aka Côte Roannaise

2/8 @ plus de vin — community.

BURGENLAND, or who makes a wine region?

what is ‘Austrian wine’ like and does Burgenland fit in?

Nittnaus, ‘Elektra‘ grüner veltliner Gols

Rennersistas, ‘Intergalactic’ welschriesling, muscat ottonel, gewürz, weissburgunder… Gols

what is a grape variety?

Meinklang, ‘Graupert’ skin contact pinot gris Pamhagen

Judith Beck, ‘Bambule’ pinot noir Gols

what responsibility do we have to history?

Claus Preisinger, ‘Kieselstein’ zwiegelt aka rotberger Gols

2/2 @ vine wine — wine 101.

SAVVY B? PINOT? DRY? ORANGE? these questions and more.

Vimbio ‘ACL’, albariño, caiño blanco, loureiro Rías Baixas, Green Spain

OR ‘DO YOU HAVE A SAUVIGNON BLANC?’

In a universe with only four commercial white wine styles, sauvignon blanc is the one that isn’t sweet (like stereotypical riesling), buttery (like stereotypical chardonnay), or tastes like nothing (like stereotypical pinot grigio).

Luckily, we live in a world with more than four grape varieties! Here, on the river that splits northern Portugal from northwestern Spain, in the mild green verdant Atlantic-facing region of Rías Baixas, zesty albariño is grown alongside two local rarities: caiño blanco (more umami-savory and saline) and loureiro (creamier and rounder).

Plenty of freshness and a kind of orange peel quality here, but there’s more going on than in your typical grocery store albariño, especially after it warms up a little.

l’Epinay ‘Clisson’, melon b Muscadet, Loire Valley 2019

OR ‘CAN WHITE WINE AGE?’

The mouth of the Loire Valley around Nantes is a place where wines won’t find richness because of the warmth of the sun. If you’re going to put meat on the bones of your fresh, high-acid white wines, you need time and a little bit of winemaking on your side.

This bottling, from historically prized granite slopes around the village of Clisson, spends three years aging on the slurry of spent yeast that falls to the bottom of the cement tanks where it ferments. The lees aging (aka spending time on that yeast slurry) gives a pillow-y, marshmallow-y cheesy richness to wine that would otherwise be all oyster shell, no give. After bottling it has spent another three years evolving under cork, with that little bit of exposure to oxygen making it more savory, soft, and contemplative.

Muscadet is often talked about as a simple shellfish wine for bistros, refreshing and crisp, but this shows off muscadet’s deeper side: candelight, kombu, and time.

Troupis ‘Hoof & Lur’, moschofilero Peloponnese, Greece

OR ‘ORANGE WINE?’

What happens when you steep skins in fermenting juice? The same thing as when you steep tea leaves in hot water: color, aromatics, texture. (The tannin molecules in grapeskins and in tea are functionally the same).

This is basically how we make red wine: steep blue-purple skins in their pale juice for the whole length of fermentation. Rosé? Really weak tea — a couple of hours, or a day at most. White? Usually no skin steeping at all — the juice runs off the press clear.

This wine, though, presents one of my favorite paradoxes: what do you get when you take a pink-skinned grape associated with direct-press white wine (here, moschofilero, a floral and delicate Peloponnese native, but it could equally be pinot gris, or gewürztraminer), ferment it on the skins like an orange wine, and end up with a wine somewhere between the color of a summer sunset, a bronze kettle, or a dark rosé?

Vine has been selling this bottle since I worked there over a decade ago, and every year it’s a little bit different. This year, the floral aromatics were really amped up — skin contact can do that, especially with naturally aromatic varieties — and it was so pink most of the class wondered whether there was any orange wine to taste at all.

What matters more? Aesthetics, or process?

Temps de Cerises ‘Avanti Popolo’, grenache, merlot, cabernet sauvignon, syrah Languedoc

OR ‘CAN I CHILL THIS RED?’

From 23-year natural wine stalwart Axel Prüfer, a great example of how grape variety (big-boy cultivars like merlot and syrah) is not destiny. A blend of direct-press juice and short maceration, it’s a wine that is all about finding freshness in a place where ripeness and intensity is a given.

It’s also a zero-addition wild child, holding itself together for our tasting but with a whisper on the finish that tells you it’ll go mousey in a few hours or the next day. We talked about how this stage of barely-there mouse can be off-putting if it’s all you’re left with but dovetails nicely with certain foods: bitter braised greens, mushrooms, barley tea, kimchi, shrimp and Thai basil…

A Tribute to Grace ‘Santa Barbera County’, grenache Santa Barbara, California

OR ‘DO YOU HAVE A PINOT?’

TKTK

Tiberio ‘Montepulciano d’Abruzzo’, montepulciano Abruzzo

OR ‘IS THIS DRY?’

TKTK

2/2 @ vine wine — industry blind tasting

1/21 @ with others — alpine wines.

BUGEY, SAVOIE, VALLE D’AOSTA. every mountain valley is an island.

Vigne Sauvage, ‘l’Insouciance’ chasselas Lake Geneva

Chasselas is a quiet, barely-there variety that, at its best, is all about minimalism and springwater clarity. At its worst, people just call it boring. You can find it in southern Baden, Alsace, and in a few pockets in Central / Eastern Europe, but the place where it gets the most respect and care is in Switzerland.

Swiss wine is, on average, carefully farmed, high quality, and drunk almost entirely by Swiss people. Only a tiny fraction is exported, and it tends to be super expensive once it makes it to the other side of the Atlantic. This is as close as we’ll get to Swiss wine in this tasting, but it’s not so far off: an hour bike ride from the border, on the French shores of Lake Geneva (Lac Lémant).

David Humbert of Vigne Sauvage farms two little postage stamps of land there that together amount to just one and a half hectares, grown on glacial scree and limestone — a little bit bigger than Gramercy Park, or a major league baseball field. He makes his wines in a little garage-sized room lined with plywood, in a handful of small vats made out of stainless steel and fiberglass, and bottles them without addition or subtraction.

des Eclaz, ‘Fleurus’ altesse Bugey

les Cortis, ‘Napées’ altesse Bugey

What is Bugey, anyway?

Let’s talk about it!

Politically it was a fief of the House of Savoy for almost 600 years, before European nation-states began to coalesce like planets. It was ceded to France in the 1601 treaty of Lyon, which concluded a yearlong war between the King of France and the Savoyards over a little French enclave in the Piedmont called Saluzzo. (Motto of the marquisate: Non sol per questo, ‘Not only because of this’.)

Geographically it’s defined by a loop of the Rhône river around the crumpled-up southernmost foothills of the Jura mountains: little island clusters of vines separated by forested limestone plateaus mostly trying to face south and soak up the sun. And those clusters are tiny — Bugey as a whole only has 500 scattered hectares under vine, a drop in the bucket compared to Saint-Joseph (~1200), Croze-Hermitage (~1800), or oh my god the southern Rhône (50,000++?!!). There are structural reasons you’ll find Côtes du Rhône in Costco and not Bugey, you know what I mean?

As for the wines themselves, it’s a place where you feel the transition between that Alpine energy and Lyon, due west, with Beaujolais orbiting that city like a purple granite moon. There’s Savoyard altesse and mondeuse, but also Burgundians like gamay and chardonnay and pinot noir. Bugey makes, proportionally, a lot of sparkling wine.

Here, we get a side-by-side of one of my favorite Alpine white grapes: altesse. (Literally, ‘your highness’.) Princess-peachy, a kind of reddish-bronze when fully ripe, like a softer chenin.

These two growers are a 24 minute bike ride from one another. Apart from all of the tiny differences that can make wines from basically the same place taste a little bit different, the biggest one here is probably the amount of air these two fermentations breathe. One was pressed into stainless steel (less air, tighter, fresher), and the other into a big 600L neutral barrel (more air, looser, wider).

Can you guess which was which?

(des Eclaz = Jean-Pierre Gros and Michel Roussille, first vintage 2017. Les Cortis = Jérémy and Isabelle Decoster Coffier, first vintage 2016. Bugey is dynamic!)

Grosjean, ‘Torette’, petit rouge Valle d’Aosta

du Fables, ‘Les Astres Invisibles’ mondeuse Savoie

The Alps are a wall, but they’re also a crossroads.

On the one hand: immense isolation, every valley its own pocket universe, like a chain of islands, each one with its own dialect and local wildflowers, an incredible diversity of genetic variation, grape varieties, and customs. The Valle d’Aosta, today Italy’s smallest wine region, has a dizzying range of native varieties, including not just petit rouge but humagne (called cornalin in Swizterland), neyret, petit arvine, prié blanc, the red-fleshed roussin de morgex, fumin,

On the other hand, connection and movement. Aosta, fiercely independent, and populated by speakers of Valdôtain, a variety of Franco-Provençal, was ruled by the House of Savoy for something like 800 years, and has had French as an official language since 1536. (It only became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.)

You can see this, too, with a grape like mondeuse, on the one hand the unique specialty red of the Savoie, on the other related both to syrah and viognier (in the northern Rhône) and teroldego (in the Italian Dolomites).

In what ways do these two red varieties remind you of each other?

How are they different?

1/18 @ plus de vin — ferment.

EMILIA ROMAGNA. a rainbow of alt sparkling

Koi, ‘Chi Mera’ pignoletto, montuni Samoggia valley, southwest of Bologna 2021

Tasted next to a Corpinnat, a Catalán grower sparkling from Mas Candí, and in fairness to all of us, this is a less straightforward comp with champagne-method sparkling than you might think!

While it’s hazier and wilder than traditional method sparkling, it is aged col fondo, on those lees, for years, after a second ferment in the bottle, which lets it tiptoe towards some of the bread-ier, yeastier, less fruit forward tones of far fancier fizzy wines.

(It’s not so much a pet-nat as a rifermentato, which we’ll come back to: rather than being bottled before fermentation is over, it’s bottled and the second ferment started with frozen juice from the year’s harvest.

This bottle was harvested in 2021, so it’s been waiting quite a while to end up in our glass!)

Koi was started by Flavio Restani in 2018 out of a collection of vine parcels farmed by his parents and grandparents. Flavio wears very technical zipped cargo pants and chose the koi for his label as a symbol of perseverance and non-conformity.

This bottling is from a single co-planted parcel of very obscure local white grapes that was planted in the early ’60s, farmed without chemicals, fermented with native yeasts, and bottled without filtration or sulfur.

Ca’ de Noci, ‘Le Rose’ malvasia di candia near Reggio Emilia

Pradarolo, ‘Vej 240’ malvasia di candia near Parma

Malvasia di candia is a lightly aromatic, orange-blossomy variety pushed further into perfume and dimension by the skin contact in both of these wines. Malvasias were prized for thousands of years for their ability to ripen to high sugars and turn into golden wines that could survive a sea voyage. They were traded throughout the eastern Mediterranean, and often named for the ports they set sail from (in this case, Candia, in Greece).

Ca’ de Noci (walnut farm) was started by brothers Giovanni and Alberto Masini way back in 1993, which makes them very early to the northern Italian natural wine party. This lightly sparkling wine (it’s sealed with a regular cork, which makes it a little nerve-wracking to open) is bottled after a short (4-5 days, I think?) time on the skins while it’s still fermenting, with a little more juice to help it along the way.

Alberto and Claudia Carretti of Pradarolo are also old-school — Alberto converted the farm to fulltime winemaking in I want to say 1989 — and their wines are slow-cooked braises, favoring long, long extractions and extended maceration, all bottled without sulfur. (In this case, 240 days on the skins in concrete tanks.) They make some sparkling wines, too, in a similiarly serious vein: very rustic champagne-method, refermenting base wines a lot like this one and then aging them on the lees for years before disgorgement.

Camillo Donati, Lambrusco mostly lambrusco maestri near ParmaQuarticello, “Barbacane” lambruscos maestri, salamino, and grasparossa near Reggio Emilia

Maybe the best way to put these two producers into context — bone-dry rifermentato from organically farmed grapes bottled with zero sulfur — is to compare them to what mainline industrial lambrusco looks like.

Riunite was a consortium of nine cooperative wineries in Emilia founded in 1950 whose lambrusco was brought to the U.S. in 1967; the wine, marketed by Banfi, was at one point the number one imported wine in the country, and at its height in the mid-80s it was selling over 11 million cases per year. Today, the co-op group has 1,450 grower members, and sales hover around 7 million cases annually. It sits on a shelf for less than $10.

For Riunite’s lambrusco, and the other conventional lambruscos like it that still dominate the market, grapes will be mechanically harvested and (largely) farmed with chemical inputs. Fermentations take place under controlled conditions, in giant steel tanks, assisted with cultured yeasts and added nutrients. After a short maceration and fermentation, the bubbles are obtained as in prosecco: a second fermentation (more yeast and sugar) in another giant tank before bottling, so the wine (unlike champagne, and unlike ancestral rifermentato) doesn’t have any of the characteristics imparted by lees in the bottle. It’s bottled after a sterile filtration and about 100ppm of sulfur addition to keep it as shelf stable as a can of Coke. (Coke has a little over 100 grams/liter of sugar; Riunite Lambrusco has 58. It also clocks in at only 8% alcohol — the 58 grams are the sugars that would have fermented it to the 12.5 or 13% of the wines we tasted.)